Public speaking: navigation, humor, insight, information, advice, and stories

As an author, I get called on to do speeches from time to time. My Writing Without Bullshit speech is now connecting pretty well, based on how audiences are reacting to it. The reason is that, like my writing, it’s tight: every slide has a purpose, and most of those purposes have a payload. It mixes up information and fun in a way that sticks.

I’ve recently given versions of this speech at the Content Marketing Conference in Boston, Content Marketing World in Cleveland, HubSpot’s INBOUND17 in Boston, PR Society of America Chapter meetings in Salt Lake City and New Hampshire, and the Northeast Ohio Oracle User Group in Cleveland. (If you think the last one is odd, I did, too, but since they were the first group to propose to pay me for a speech I wasn’t about to say no.) I’ve also done extended versions of this in about a dozen workshops. As a result, I’ve honed the material and learned just what resonates with an audience. And it appears to be working, if I can believe the tweets and what it feels like in the room.

There’s a lot of laughter in the audience, but I’m not there just for laughs. I want people to learn something. After all this practice, I’ve honed the speech until it includes only stuff that counts: guideposts, bits that make people laugh, bits that make people think hard, and bits that they take away. I’ve become convinced that it’s the mix of these pieces that enables the speech to connect.

Guideposts — necessary, but short

In a 40-minute speech, people need to know what’s coming. It helps them to trust you. But every moment you spend on navigation is a luxury; people will get bored with it real quick. For example, near the start of the speech I post this slide:

I spend about 20 seconds on this, since it doesn’t actually teach anything or connect with the audience, but it relaxes people since they know where I’m going.

Humor to create warmth and trust

Everyone in the room is laughing early on in the speech, and then frequently throughout. I’ve thought carefully about that. I love it, because it means the audience likes me, and they’re not going to learn unless they like me and feel open to what I am saying. Candidly, I like the attention — it’s reassuring. But I don’t make jokes for the sake of jokes, and unlike speakers like Adam Grant, who gave a keynote at INBOUND, I don’t use cartoons. When you laugh at one of my remarks, you’re going to remember it, and you’re going to learn something. For example, I take apart this pompous job description from Johnson & Johnson:

I read this out loud. About halfway through I stop, out of breath. “Pro tip,” I say, “If you have to take a breath in the middle of a sentence, it’s too long.” Then I ask the audience what kind of a job this. Typically no one guesses right. So I explain:

This is a sales job. “Sustainable strategic relationship?” That means you play golf with someone. “Continuous process improvement?” That means you learn from your mistakes. “Export key learnings?” That means what you learn, you write down and share with others.

This connects. For one thing, the bamboozlement around what the text actually means creates tension, which I resolve by explaining that it’s a sales job. And the simple explanations like “play golf with someone” drive home the point that complicated jargon-filled language is obscuring the much simpler reality of what salespeople do, which is to form relationships.

It helps that this is a real job description from a real company that everyone has heard of.

When I make people laugh, I always want them also to say “Oh, jeez, he’s exactly right.” And they’ll remember those points. That’s why I don’t just tell jokes with a tenuous connection to the content.

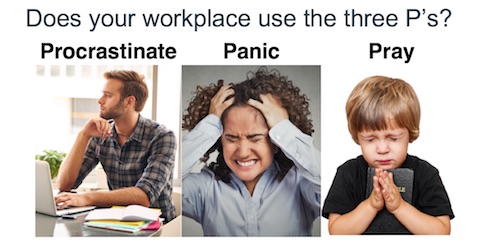

Sometimes the joke is to make people look at themselves and understand their own absurd thinking. Here is my “three P’s process for writing”, which I deliver in a totally deadpan tone, revealing it one step at a time:

People immediately laugh when I reveal that the first step in the writing process is “Procrastinate.” But I can tell from all the heads nodding that everyone is quite familiar with this process and knows how terrible it is. This sets them up nicely for my suggestion about a more disciplined process: Prepare, Draft, Revise.

One more thing about humor: My natural personality is a sarcastic smartass. That works for me on stage. Other speakers use humor differently. Ann Handley makes fun of herself and others in a way that’s a lovable and good natured — that works very well for her. Kathy Klotz-Guest is an improv comedian, so you just want to laugh because she is funny and friendly. Both are effective with humor. Neither of them could adopt my mean-spirited smartass persona and succeed, nor could I succeed with their friendlier presentation. It helps to lean into — or play off of — whatever you do naturally.

Insight that people will remember

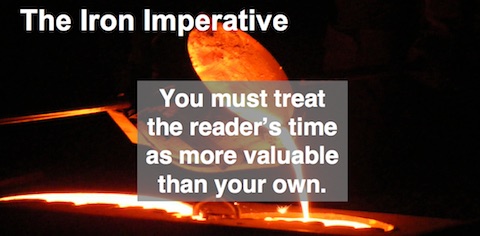

If your speech doesn’t leave people thinking differently about what they do, you’ve failed. One way to do this is to just create a slide with an important insight on it. Here’s one of mine:

A few things about these. First off, this is early in the speech, but not at the very beginning — I need to prove the point a little before I sum it up. And the number of slides like this in a speech should be limited. You want them to remember one or two or three insights, not eight or ten or 20. Insights are heavy; humor is light. You need a balance or your speech becomes ponderous.

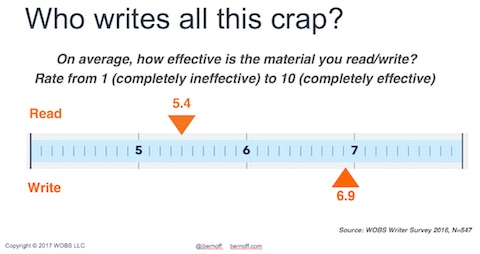

Data can also deliver insights, but you have to explain and present it right. For example, here’s my chart showing how we rate the material we read and write on a typical day:

In this case, first I reveal the top pointer, then a little later, the bottom one. And I point out that while we rank what we read as mediocre, we all think we write better than that. “So now you know who writes all this crap,” I say. “Other people.”

It is at this moment, I hope, that the listener realizes that they are, indeed, part of the problem and need to change.

Information without overload

Every speech has information. But delivered in the form of a speech, information can rapidly cause the audience to glaze over. Two things matter here — one, present the information in as interesting a way as possible, and two, present less detail to prevent information overload.

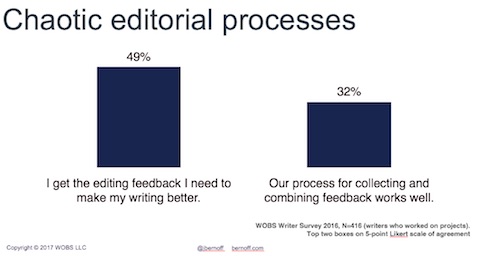

Here’s one information slide from my speech:

I present this because the data point on the right — that only 32% of people doing writing projects feel their feedback process works well — shocked me when I collected it. This is a crisis in writing processes that everyone suffers but no one talks about. I have more data about how this differs among writers, editors, and managers, but I don’t present it. I want people to remember the one point — that their processes work poorly — and then explain how to make it better.

Advice is great, in moderation

If you offer no advice in your talk, you are doing the audience a disservice. If they don’t know what to do about what you are saying, why did they bother listening?

If you offer too much advice, of course, you become a harridan. Nobody likes a nag.

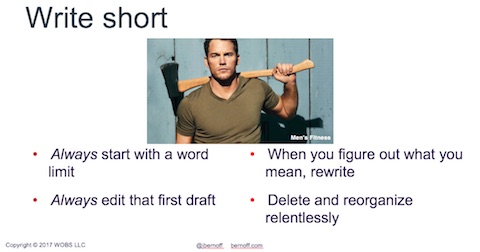

My advice slides are typically bullet points, but I try to keep the number of points in control and add an image that helps focus people. People are always retweeting this slide, for example:

There’s something about Chris Pratt with an axe, ready to trim your bloated writing, that focuses the mind. And when I tell you to think about Chris Pratt with an axe when you are writing too long, perhaps you will remember.

Stories work, so long as they have a point

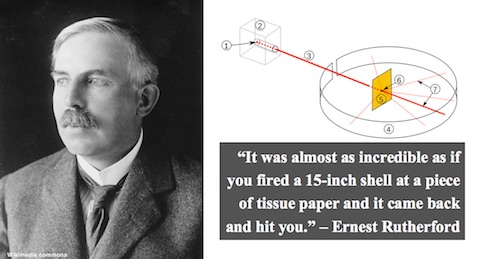

Speakers love to tell stories, and audiences love to hear them. The challenge is when the listener pops up out of story-listener mode and says “why did you tell me this?” Stories also take a long time to tell well. So I only use a few of them in each speech. For example, I tell the story of how Ernest Rutherford figured out that 99.9% of everything is empty space — and how I felt the same way as I observed that most of the words in what we read are meaningless bullshit.

Final thoughts

Putting this all together, I’ve learned:

- Humor and stories are essential for making people like you.

- A good speech, at least for me, mixes up information and advice with some fun stuff.

- Give people an idea what’s coming and what’s important.

- Use your body and your voice to reflect these changes in tone.

- Practice a lot. Refine what works and dump what doesn’t.

Josh — why do you think presenting to a crowd of database technologist odd? Engineers and other technical types need to learn how to better communicate in the same way professional writers need to improve their craft. Engineers are rarely, if ever, given opportunities to focus on this aspect of their jobs. Your speech was one of the rare opportunities we have to think about this aspect of our jobs.

Rumpi, you are a visionary. I was excited to speak to your group, it was a terrific experience, and they were extremely interactive and appeared to learn a lot. It just seemed odd to me that of all the groups that could have reached out to me, the first one was a group of technical users. Regrettably, the rest of the coding and database world have not followed your lead. So let’s not call it odd, let’s call it badly needed and much ignored outside of the enlightened parts of the Great Lakes database community.

I was in the audience for your presentation at Content Marketing World. Your material resonated with me and I use it every day in my freelance writing. You put into words what I had felt about messages on websites. I also learned I contributed to the jibberish. Thanks for sharing your wisdom!