Paul Romer set out to reform writing at the World Bank. He lost his job.

Paul Romer ran research for the World Bank. He took aim the bank’s impenetrable writing style, known as “Bankspeak,” asking for shorter, more pointed reports. That cost him his management position. I’ll explain what he was right about, why it didn’t work, and what it really takes to fix a writing culture like this.

Romer’s objections about bank writing are spot on

You can read a mirror copy of Romer’s internal blog here. His post on writing had me cheering. Let’s start with this:

Writing clearly and concisely is a time consuming, multi-stage process that starts with composing and is followed by multiple rounds of editing, pruning, and user testing. The essence of this process is captured by the apology that “I would have written less but I didn’t have the time.”

The quality of written prose should be higher in documents that will have many readers. If an author devotes an extra hour to shortening and improving a text, this might save an additional minute for each reader. If there are even 100 readers, an extra hour of editing that saves 100 minutes of reading reduces the total time required for communication.

Sounds a lot like The Iron Imperative. And Romer takes the responsibility for this onto himself:

DEC [Development Economics Group, the Bank’s research arm] should be the part of the Bank that prevents the entire organization from using . . . vague persuasion. But we can be the voice that criticizes vague overstatement only if we are consistent in setting and meeting high standards for clarity of our prose and are willing to admit a mistake when we make one.

So to build trust, the highest priority for the Office of the Chief Economist [that is, Romer] will be to insist that any document that this office produces is written clearly, concisely, and is correct to the best of our knowledge. We may not be able to prevent other units from publishing poorly written documents, but nothing will prevent us from keeping track of the relative strength and weaknesses of all bank publications.

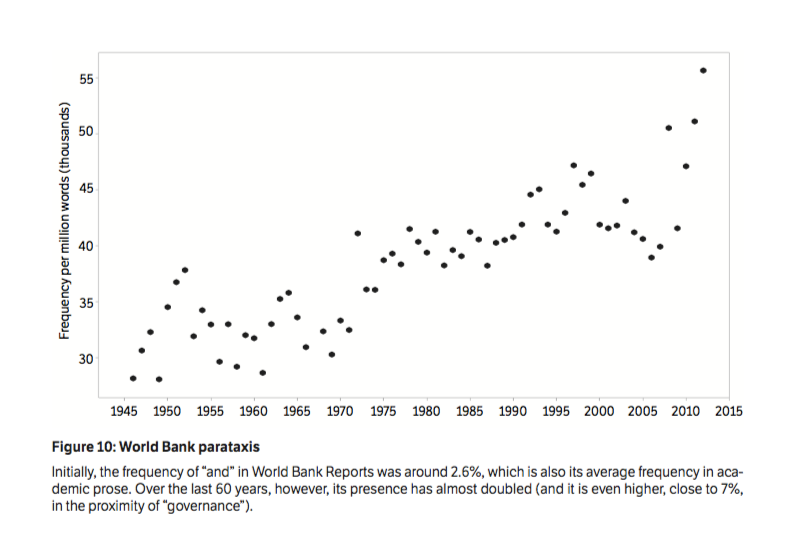

He has identified the word “and” as a problem, an observation that I’ve also made. But he went further and charted it over time.

When 7% of the words in your reports are “and,” you’ve got a serious readability problem.

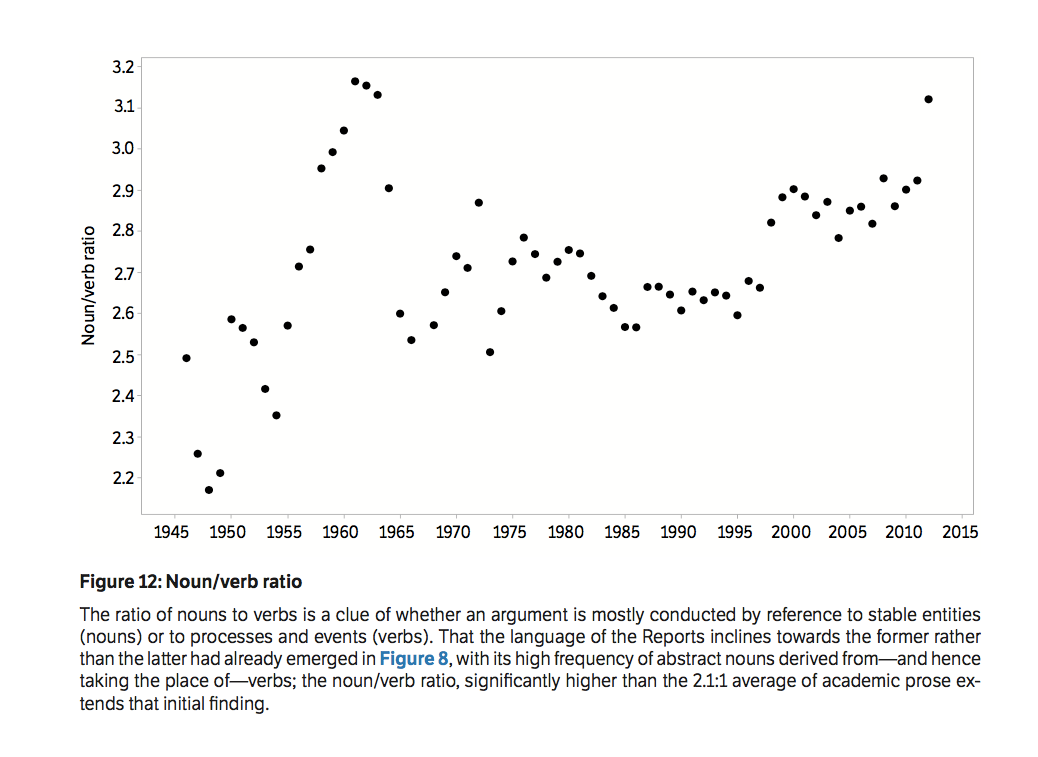

Then he points out that the Bank’s publications are drowning in nouns over verbs, a common problem of prose that’s attempting to sound sophisticated.

These are worthy goals. So what went wrong?

You can’t change writing from the top

According to Bloomberg, here’s how Romer described what happened:

Romer said he met resistance from staff when he tried to refine the way they communicate. “I was in the position of being the bearer of bad news,” he said in an interview. “It’s possible that I was focusing too much on the precision of the communications and not enough on the feelings my messages would invoke.”

And here’s how The Guardian described it:

He had asked for shorter emails, while also cutting staff off if they talked for too long during presentations, it said.

He . . . added “everyone in the Bank should work toward producing prose that is clear and concise. This will save time and effort for a reader. Thinking about the reader is an example of what I mean when I say that we should develop our sense of empathy.”

In an email to staff, Romer argued that the bank’s flagship publication, World Development Report, would not be published “if the frequency of ‘and’ exceeds 2.6 percent,” according to Bloomberg. He reportedly cancelled a regular publication that did not have a clear purpose.

A 2015 study by Stanford University’s Literary Lab found World Bank publications seemed almost to be “another language”. The study coined the term “Bankspeak” to describe report styles becoming “more codified, self-referential, and detached from everyday language.”

While I am no economist, I am a student of the challenges that organizations face with entrenched writing cultures. I am certain that the highly intelligent and accomplished analysts and economists at the World Bank feel they understand their topics and audiences better than anyone else. They are used to writing in “Bankspeak” and it’s probably a point of pride that they not only create it, but understand it. When your status depends on a perception of superior intellect, there is very little reason to change.

And when a manager from outside takes over and insists on changes in language, you’re going to get resistance. If Romer had insisted that all the research staff wear red ties and sandals, or stop eating meat, or talk to each other instead of sending emails, the result would be the same. As Peter Drucker said, “culture eats strategy for breakfast.” No amount of jumping up and down — or logic — can change it.

Culture change approaches that work

Here are my steps to change a poor writing culture:

- Generate awareness

- Share knowledge

- Provide help and support.

It seems as if Romer completed Step 1 and stopped partway through Step 2.

If you really want to create change like this, you need to provide people with tools and training on how to write better. For example, you could:

- Recruit a small, committed group who want to change, give them the editorial help they need, and create a small success. Then use that group to help change the company.

- Run a workshop on good writing, using actual samples from the organization as examples.

- Create a writing center to provide help, then encourage volunteers to get editing and coaching from the writing experts. (That approach worked for Jessica Weber at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, an environment that’s probably got a lot in common with the World Bank.)

Cultural changes like this take time and planning to execute, but they are possible. If you underestimate cultural inertia, then even if you’re in charge, forcing change on people could cost you your job. And that appears to be what happened to Paul Romer.

The only thing I’d add: in step 1, along with awareness, you have to generate buy-in. This goes for any process change — whether it’s changing the corporate brand (of which writing style is a component) or introducing new software. I was on the receiving end of a change like this, and it went poorly because no one ever bothered to ask for our buy-in. If they’d shown us why the current system was falling short — for example, how customers and clients were struggling to understand the reports, or how we were actually losing business — our resistance would’ve melted.

I don’t know much about the world bank, but I do recall that Alan Greenspan at the Federal Reserve was successful with his practiced inscrutability . I imagine bankers have strong incentives to keep their proscriptions Delphic. Or to put it another way, maybe Romer was knocking down Chesterton’s Fence.

I find it hard to believe that a well known, highly paid chief economist at a large international organization like the World Bank would be shoved aside principally for trying to get researchers to write better. No, there’s more going on here than that. Known as a contrarian long before he took the job, I think Romer clashed with his staff and his management over many issues – perhaps his vision for his organization, overall leadership style, and his view of priorities. Maybe bank management felt he was spending too much time pushing things like writing skills and not enough time on issues like bank strategy. Note that he is still the bank’s chief economist, so they clearly value his technical skills.

Thomas Hayden is right. Romer clashed with the executive board and other senior managers. Researchers have no influence on high level appointments or demotions.

Josh, I passed your blog post onto some friends at various international financial institutions and got a very different perspective: According to various sources, he didn’t get ‘demoted’ because of this. This was the last straw. He’s well-known to be rather egocentric and probably shouldn’t have had the job anyway.

This was as much a political maneuver by a Managing Director as Romer not knowing how to get his point across and spending more time alienating people than getting a job done.

Full disclosure: I am a former World Bank staff member. The three steps to improving writing that are listed above capture the essence of the issue. Romer was right in trying to improve writing, but he should’ve paid more attention to the third item, namely, provide help. He did not appear to understand that the World Bank’s staff is drawn from nearly 110 countries, and while the staff members are no doubt well trained in technical economics, their first (and frequently even second) language is not English. As manager of a large country department, I had to regularly organize training sessions in report writing that provided examples, advice, exercises, and individual support. Needless to say, these things carry substantial budgetary implications.