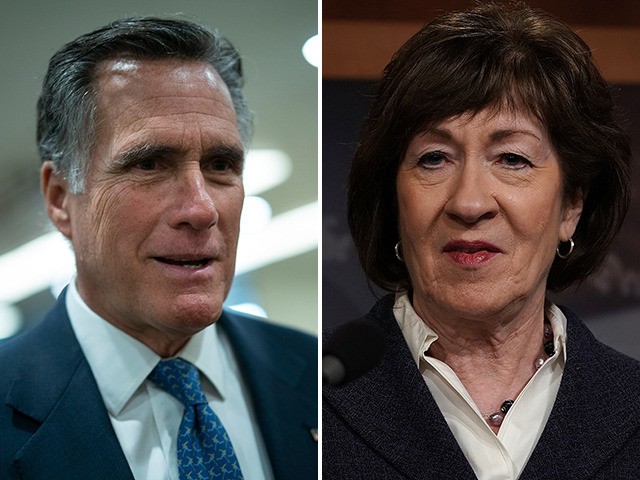

No bullshit impeachment statements from Mitt Romney and Susan Collins

On Saturday, Republican Senators Mitt Romney and Susan Collins joined five other Republicans and all the Democrats and independents in the Senate in voting to convict former President Trump in the impeachment inquiry. Rather than equivocating, these Senators issued direct, clear, and declarative statements.

Mitt Romney’s statement is short and direct

Romney, the only Republican Senator who had voted to convict Trump in the previous impeachment, issued this minimalist statement:

After careful consideration of the respective counsels’ arguments, I have concluded that President Trump is guilty of the charge made by the House of Representatives. President Trump attempted to corrupt the election by pressuring the Secretary of State of Georgia to falsify the election results in his state. President Trump incited the insurrection against Congress by using the power of his office to summon his supporters to Washington on January 6th and urging them to march on the Capitol during the counting of electoral votes. He did this despite the obvious and well known threats of violence that day. President Trump also violated his oath of office by failing to protect the Capitol, the Vice President, and others in the Capitol. Each and every one of these conclusions compels me to support conviction.

These 133 words are completely in active voice and include no qualifiers or weasel words. If you want to quibble, you could take issue with the redundancy of “each and every one,” but other than that, it’s about as brief, clear, and direct you can get.

When he was our governor in Massachusetts and later ran for President, Romney shifted positions on issues like abortion frequently enough to paint him as a flip-flopper. But since being elected in Utah, he has voted his conscience, heedless of the cost in angering Trump voters.

Susan Collins goes on at length, but is similarly direct

Self-styled moderate Susan Collins from Maine, the only Republican Senator from New England, had voted against the previous impeachment, saying that Trump had “learned his lesson.” (He didn’t.)

But this time around, the newly re-elected Collins voted to convict. It took her 1300 words to say what Romney said in 130. Here’s her statement with commentary.

The hallmark of our American democracy is the peaceful transfer of power after the voters choose their leaders. In America, we accept election results even if our candidate does not prevail. If a candidate believes that there is fraud, the courts can hear and decide those issues. Otherwise, the authority to govern is vested in the duly elected officials.

On January 6, this Congress gathered in the Capitol to count the votes of the Electoral College pursuant to the process set forth in the 12th Amendment to the Constitution. At the same time, a mob stormed the Capitol determined to stop Congress from carrying out our constitutional duty. That attack was not a spontaneous outbreak of violence. Rather, it was the culmination of a steady stream of provocations by President Trump that were aimed at overturning the results of the presidential election.

The President’s unprecedented efforts to discredit the election results did not begin on January 6. Rather, he planted the seeds of doubt many weeks before votes were cast on November 3. He repeatedly told his supporters that only a ‘rigged election’ could cause him to lose. Thus began President Trump’s crusade to undermine public confidence in the presidential election — unless he won.

Early on the morning of November 4, as the ballots continued to be counted, President Trump claimed victory and asserted that Democrats were trying to ‘steal’ the election. On November 8, the day after several media outlets had declared Joe Biden the apparent winner based on state-by-state results, President Trump tweeted ‘this was a stolen election.’ With that, his post-election campaign to change the outcome began.

Up to this point, Collins’ statements are a simple recitation of the facts in the order that they happened.

Over the ensuing days and months, the President distorted the results of the election, continuing to claim that he had won while court after court threw out his lawsuits and states continued to certify their results. President Trump’s falsehoods convinced a large number of Americans that he had won and that they were being cheated.

The President also embarked on an incredible effort to pressure state election officials to change the results in their states. The most egregious example occurred on January 2. In an extraordinary phone call, President Trump could be heard alternating between lobbying, cajoling, intimidating, and threatening the election officials in Georgia. ‘I just want to find 11,780 votes,’ he stated, seeking the exact number of votes needed to change the outcome in that state. Despite the President’s pleas and threats, the Georgia officials refused to yield to the presidential pressure as did state officials in other states.

At this point, the account begins to move into emotional rather than factual territory. Weasel words (ill defined qualifiers and intensifiers) start to appear, including “large number of Americans,” “incredible,” “egregious,” and “extraordinary,” as well as emotionally charged words like “falsehoods,” “threatening,” and “pressure.” (I am documenting the shift in language, which is real independent of whether you believe the statements are accurate.)

In December, President Trump’s post-election campaign became focused on January 6 – the day that Congress was scheduled to count the Electoral College votes. Although this counting is a ceremonial and administrative act, it is nevertheless the constitutionally mandated final step in the electoral college process, and it must occur before a new president can be inaugurated.

On December 19, President Trump tweeted to his supporters: ‘Big protest in D.C. on January 6th. Be there, will be wild!’ In response, some of his campaign supporters changed the date for protest rallies they originally had scheduled to occur after the inauguration to happen instead on January 6.

Having failed to persuade the courts and state election officials, President Trump next began to pressure Vice President Mike Pence to use his role under the 12th Amendment to overturn the election. The President met with Vice President Pence on January 5, then increased the pressure by tweeting hours later: If the Vice President ‘comes through for us, we will win the Presidency.’ That’s what his Tweet said.

Vice President Pence, however, refused to yield. He issued a public letter on January 6 making clear that his ‘oath to support and defend the Constitution’ would prevent him from unilaterally deciding ‘which electoral votes should be counted and which should not.’

Now we’re back to a simple narrative about what happened.

During his speech at the Ellipse on January 6, President Trump kept up that drumbeat of pressure on Vice President Pence. In front of a large, agitated crowd, he urged the Vice President to ‘stand up for the good of our Constitution.’

‘I hope Mike has the courage to do what he has to do,’ President Trump concluded.

Rather than facilitating the peaceful transfer of power, President Trump was telling Vice President Pence to ignore the Constitution and to refuse to count the certified votes. He was also further agitating the crowd, directing them to march to the Capitol.

Collins sets the stage with more facts.

In this situation, context was everything. Tossing a lit match into a pile of dry leaves is very different from tossing it into a pool of water.

And on January 6, the atmosphere among the crowd outside the White House was highly combustible, largely the result of an ill wind blowing from Washington for the past two months.

President Trump had stoked discontent with a steady barrage of false claims that the election had been stolen from him. The allegedly responsible officials were denigrated, scorned, and ridiculed by the President, with the predictable result that his supporters viewed any official that they perceived to be an obstacle to President Trump’s reelection as an enemy of their cause.

That set the stage for the storming of the Capitol for the first time in more than 200 years.

Collins’ metaphor of the lit match and the combustible situation is telling. The literalist Senators who rejected the impeachment were unwilling to connect the dots and see what Trump did as incitement. Collins eschews that defense and makes it clear that she holds Trump responsible.

Nearly 30 minutes after the Capitol first came under attack, Members of Congress, law enforcement, and everyone else here in the Capitol waited in vain for the President to unequivocally condemn the violence and tell his misguided supporters to leave the Capitol. Rather than demand an end to the violence, President Trump expressed his frustration once again that the Vice President had not stopped the vote certification as he had urged. Shortly after the Vice President was whisked away from this very Chamber to avoid the menacing mob chanting ‘Hang Mike Pence,’ President Trump tweeted, ‘Mike Pence didn’t have the courage to do what should have been done.’

Instead of preventing a dangerous situation, President Trump created one. And rather than defend the constitutional transfer of power, he incited an insurrection with the purpose of preventing that transfer of power from occurring. Whether by design or by virtue of a reckless disregard for the consequences of his actions, President Trump, subordinating the interests of the country to his own selfish interests, bears significant responsibility for the invasion of the Capitol.

Remember, these Senators were present in the Capitol during the time of the insurrection. Collins clearly felt as if Trump had abandoned his duty to keep them safe.

This impeachment trial is not about any single word uttered by President Trump on January 6, 2021. It is instead about President Trump’s failure to obey the oath he swore on January 20, 2017. His actions to interfere with the peaceful transition of power – the hallmark of our Constitution and our American democracy – were an abuse of power and constitute grounds for conviction.

Now we read the actual offense, which Collins states logically and straightforwardly.

Two arguments have been made against conviction that deserve comment. The first is that this was a ‘snap impeachment,’ that the House failed to hold hearings, conduct an investigation, and interview witnesses. And that is true. Without a doubt, the House should have been more thorough. It should have compiled a more complete record. Nevertheless, the record is clear that the President, President Trump, abused his power, violated his oath to uphold the Constitution, and tried almost every means in his power to prevent the peaceful transfer of authority to the newly elected President.

Second is the contention that the First Amendment protects the President’s right to make any sort of outrageous and false claims, no matter the consequences. But the First Amendment was not designed and has never been construed by any court to bar the impeachment and conviction of an official who violates his oath of office by summoning and inciting a mob to threaten other officials in the discharge of their constitutional obligations.

A direct and clear dismissal of the counterarguments.

My vote in this trial stems from my own oath and duty to defend the Constitution of the United States. The abuse of power and betrayal of his oath by President Trump meet the constitutional standard of ‘high crimes and misdemeanors,’ and for those reasons I voted to convict Donald J. Trump.

Finally, Collins returns to the issue and hand and concludes her reasoning.

Susan Collins has a reputation of taking middle positions, neither fully conservative nor fully liberal, which probably accounts for her survival as the only moderate Republican in a mostly liberal part of the country. Some of her equivocations in the past have seemed strained. But in this case, her narrative is clear and persuasive.

I’m trying to figure out how anyone could read these no-bullshit statements and still vote not to convict President Trump. The constitutional arguments regarding convicting former officials, while not addressed in these statements, are weak — if you can’t convict an ex-President, then there is no way to punish him for acts taken at the end of his term, and no way to disqualify him from running again. The narrative, as laid out by Senator Collins, is clear and damning.

I’d be happy if we never had to go through this again. But that hope is probably overoptimistic, given the currently polarized state of our “union.”

Shays’ Rebellion, the Boston bankers’ foreclosure of the Western Mass foreclosures of Rev War Veterans still unpaid, prompted Thomas Jefferson to express the view that “a little rebellion now and then is a good thing for America” in a now-famous letter to Madison.

What happened on June 6 was a demonstration conflated by an incompetent Capital Police which had no plan, training, or equipment to keep Congress safe and deal with a crowd that was not going after the police, but merely wanted to mostly respectfully trespass the Building (i.e. didn’t trash the many portraits on the walls).

Capital Police fired the only shot. What if there was a Timothy McVey embedded?

Had Romney and McConnell bravely faced the crowd, allowed them to sit-in in the Senate and make their voices heard, this demonstration would have passed with a footnote?

************************

History of Civil Disobedience “Sit-Ins”

Chanting slogans like “Kick the ass of the ruling class-end war research”, students marched to the Sloan building on October 3 and attempted to enter a closed meeting of the MIT Corporation-the body (still) responsible for deciding how MIT is run. The marchers were confronted at the entrance by the administration and the campus police, and after a brief struggle with the administration and campus police, a handful of the marchers were allowed into the meeting. Almost two weeks later, the October 15 moratorium took place. 100,000 people protesting the Vietnam War rallied on Boston Common and listened to speakers that included professor Howard Zinn (A People’s History of the United States). In November, 300 students participated in a sit-in near the administrative offices of building 3. The goal was to obstruct these offices until the administration capitulated to the demands of the protesters (the demands hadn’t really changed since the last action). After several attempts by authorities to break through the sit-in, the demonstrators left peacefully after three hours.

Throughout the campus actions, President Johnson had maintained that it wasn’t in his power to end government funded research, a claim the protesters apparently ignored. The sit-in tactic was used again in January as students broke into and occupied the office of MIT president Howard Johnson. When authorities threatened arrest, the demonstrators left only to march to the house of President Johnson, again demanding an end to war research.

On April 30, 1970 Nixon announced to the world that U.S. soldiers had invaded Cambodia. Campuses around the country mobilized to strike. 1,500 students voted to strike on May 5. With the news of the four students at Kent State shot to death by the National Guard, and with the support of the faculty and administration, students filled Kresge Oval with placards and anti-war sentiments, as classes were cancelled for the week. MIT was mobilized. The Bush room was turned into communication central as MIT students began outreach campaigns all over the state. Students distributed information about the war to the public, postcards were sent to congressmen, the neighboring high schools were given guidance by MIT students as to mobilizing efforts on their own campuses.

Before the war in Vietnam was over, thousands more would rally on the Common, and MIT students would continue demonstrating for peace.

This is irrelevant. The issue is whether Trump incited the riot, not the history of riots.

Yep.