Nichelle Nichols and the integration of the fans and nerds

Nichelle Nichols, best known for playing Lieutenant Uhura on Star Trek, died yesterday. Most of what you’ll read about her celebrates her rule as a trailblazer for Black actors on network television, and what that did for America’s perception of Black people. I’d like to talk about what her appearance meant for me, a sheltered white boy in the affluent and pale white suburbs of Philadelphia.

My childhood (lack of) experience of Black people

Put simply, as a child, I had no significant interaction with Black people.

A Black woman cleaned out house once a week. There were no Black kids that I remember in my elementary school — and only one Black teacher, the gym teacher. By the time I got to high school, about 10% of the kids were Black. There was still only one Black teacher, the same gym teacher who’d been in my elementary school.

This was the early 70s when there was lots of discussion about race, but very little engagement. There was not much bigotry that I can remember — the ideas of equality and tolerance were certainly what we were learning and talking about in social studies class. But it was all theoretical. While there was no explicit segregation in the school, the white kids and Black kids didn’t interact much. The Black kids all came from a different neighborhood, and were generally poorer than the white kids. I saw very little in the way of racial tension — we just did our stuff and they did their stuff and we coexisted without any reason to have much of an opinion of each other.

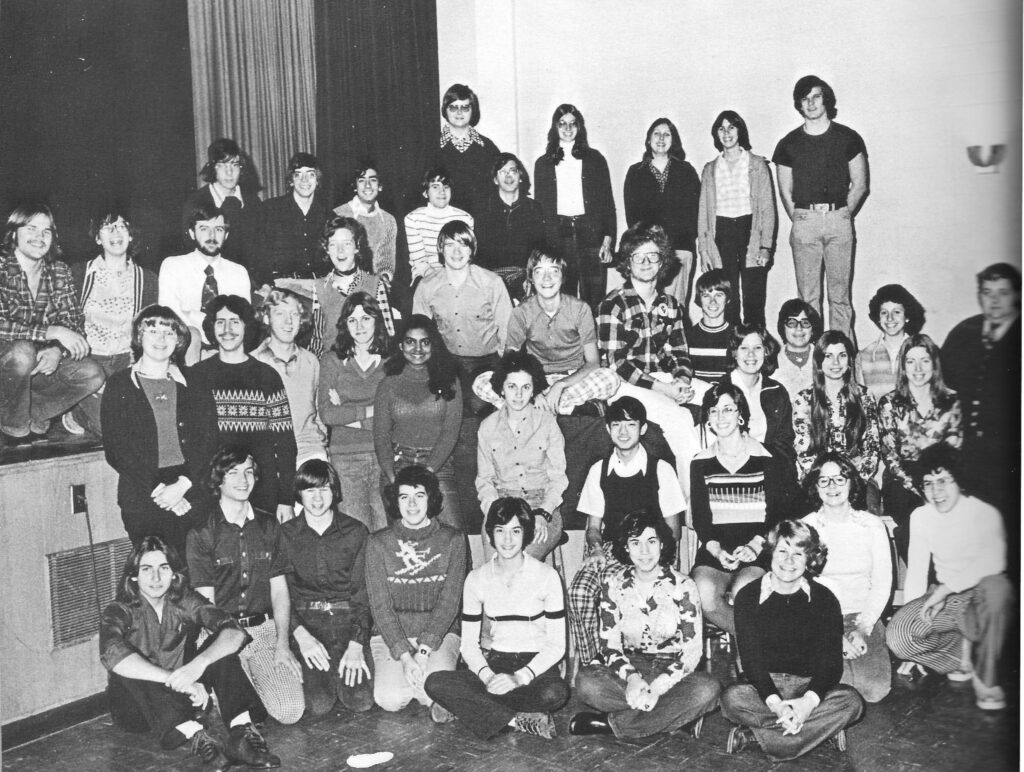

I was a nerd (although that word hadn’t really caught on yet). I was in all honors classes and focused on science, math, and English. My friends were in those same classes. The photo in my yearbook of the Ecology Club (hey, it was the 70s); it has about 35 students in it, of which all but one were white and one was South Asian. The Honor Society had 35 kids, all white. You hang out with your clique in high school, and mine was full of white kids.

My only interaction with the Black kids was as statistician for the football team. I sat up in the press box with the other statistician, Flossie, and we kept track of what happened on each play — who tackled, who ran, who caught the pass, how many yards. Much of the team was Black, and Flossie was, too, but it’s not like we were friends — she knew all the players quite well, so she’d tell me, often excitedly, that Fred or Charlie just caught the pass and I’d write it down. On the bus on the way home from away games, there’s no way the players, who were twice my size, would talk to me — they had just sweated their way through a tough experience together, one that I had nothing to do with.

Star Trek changed things

Star Trek (The Original Series) aired from 1966 to 1969. I was eight at the start of that run; while my parents watched it, they deemed it too mature for me. But I watched it (and The Animated Series) incessantly in reruns in my teens. Nobody got tattoos back then, but if I did, the tattoo would have said, “He’s dead, Jim” or “Beam me up, Scotty.”

For those of us who watched, Star Trek was our model of what the future ought to be like. It wasn’t perfect — it’s incredibly sexist, with the short-skirted female crew and the “captain’s yeoman” as female window dressing — but the series creator Gene Roddenberry clearly wanted to show a crew in which humanity and its allies had put racial issues behind them.

Nichelle Nichols’ portrayal of Uhura was solidly at the center of that idea. She was an essential member of the bridge crew, even if for most episodes, she acted as a glorified switchboard operator. (Asked her favorite episode, Nichols once quipped, “Any time where Uhura got off the bridge.”)

She did get a few opportunities to show off more acting versatility — pretending to be an evil version of herself in a midriff-baring uniform in “Mirror, Mirror;” singing, sometimes accompanied by Mr. Spock, in the crew lounge; cooing over tribbles in “The Trouble with Tribbles;” telekinetically forced to kiss Captain Kirk in “Plato’s Stepchildren;” having her memory erased and relearning to read in “Changeling;” and fighting in an arena against other slaves in “The Gamesters of Triskelion.”

But what mattered more than all of this was Uhura’s role as a professional in the crew. As a lieutenant, she clearly had the respect of the rest of the bridge crew, much more so than the white women in the crew whose roles were often little more than the sexiest possible love interests for Captain Kirk, Dr. McCoy, or Mr. Spock.

And you may not have noticed it, but Uhura actually takes over the helm when she’s needed in an emergency. She’s trained and she’s got skills, even if they didn’t make a big deal about it.

The presence of Uhura, as portrayed by Nichols, stated without the usual heavy-handed speechifying on Star Trek that Black people belonged alongside everybody else running the starship. And that mattered. As Whoopi Goldberg recalled, when as a child she first saw Uhura on Star Trek, she shouted out “Momma! There’s a Black lady on television and she ain’t no maid!”

It wasn’t just Uhura. There was a Black doctor that subbed for Dr. McCoy on occasion, and had to treat Mr. Spock by slapping his face repeatedly — an image that certainly would have challenged audiences in the 1960s. Star Trek also made what at the time was a daring choice to cast the estimable Black actor William Marshall as the brilliant but tragically egotistical computer scientist Dr. Daystrom. And in one of the cleverest episodes, Trek skewered the futility of racial prejudice in “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield,” in which Frank Gorshin, an alien policeman named “Bele” tasked with enforcing racial prejudice against people whose faces are colored the opposite of his, engages in this astounding exchange:

BELE: It is obvious to the most simpleminded that Lokai is of an inferior breed.

SPOCK: The obvious visual evidence, Commissioner, is that he is of the same breed as yourself.

BELE: Are you blind, Commander Spock? Well, look at me. Look at me!

KIRK: You’re black on one side and white on the other.

BELE: I am black on the right side.

KIRK: I fail to see the significant difference.

BELE: Lokai is white on the right side. All of his people are white on the right side.

SPOCK: Commissioner, perhaps the experience of my own planet Vulcan may set an example of some value to you. Vulcan was in danger of being destroyed by the same conditions and characteristics which threaten to destroy Cheron. We were once a people like yourselves, wildly emotional, often committed to irrationally opposing points of view, leading, of course, to death and destruction. Only the discipline of logic saved my planet from extinction.

BELE: Commander Spock, I am delighted that Vulcan was saved, but you cannot expect Lokai and people like him to act with self-discipline any more than you can expect a planet to stop orbiting its sun.

Back to the fans and the nerds

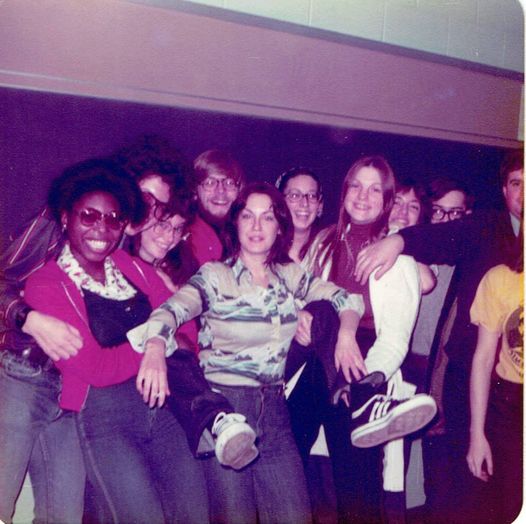

Naturally, when I arrived at Penn State in 1976, I sought out other science fiction fans. I was soon treasurer of the (yes, this was real) United Federation of Star Trek Fans. And while we were certainly not in a position of esteem among the rest of the students, we esteemed each other.

And there were Black fans in the group, with every bit as much commitment to the ideal of Star Trek as the white fans. It certainly seems likely that, seeing Nichelle Nichols on the screen, much like Whoopi Goldberg, they said to themselves, “That could be me.”

We had a good time together, and for the first time I found myself in a tight social group that was not all white. We didn’t talk much about race. We talked about science fiction and the future and, of course, what it would take to get Star Trek back on the air, which didn’t happen for another decade.

When Nichelle Nichols was ready to quit Star Trek after the first season, no less a figure than Dr. Martin Luther King talked her out of it, explaining that America needed to see her up on that screen every week, to normalize the idea that Black people belonged in spaces as key contributors where people are working together to get useful things done.

Let’s be honest. It’s a small thing, acting in a TV series as a glorified switchboard operator who bares her navel on occasion to appeal to the male gaze. But that small thing, as Dr. King recognized, was essential to getting the next generation of white boys, like me, to develop not just “tolerance” but appreciation and respect for Black people in professional spaces, like the bridge of the starship Enterprise, and social ones, like the United Federation of Star Trek Fans.

It was a small but essential first step. And as tough as things are with racial justice in America right now, we’re further ahead than we ever would have been, thanks to Nichelle Nichols as Lt. Uhura.

I am about the same age as you, although my parents were cooler than yours as they let me watch Star Trek when it was on network TV. And like you, it had a great influence on me; while “Let that be your last battlefield” wasn’t the best episode of the show, I would argue that it was one of the most important. It was the one that taught millions of kids that racism is complete and utter bullshit.

Thanks for this thoughtful post on an otherwise sad day for us all.

May we all live long and prosper in a more tolerant world.

I’ll admit that I’ve never fully appreciated the original Star Trek series as much as its successors. Hopefully Nichelle was able to enjoy how more fully developed Celia Rose Gooding’s portrayal of Uhura 50 years later has been and how much screen time she actually gets in each episode.

(On Strange New Worlds)