Newsletter 22 August 2023: Think twice before automating; corpus-robbers; ification-ification

Week 6: Railing against automation, purloined corpus, everybody’s -ificiationizing, plus 3 people to follow, 3 great reads, and plugliness.

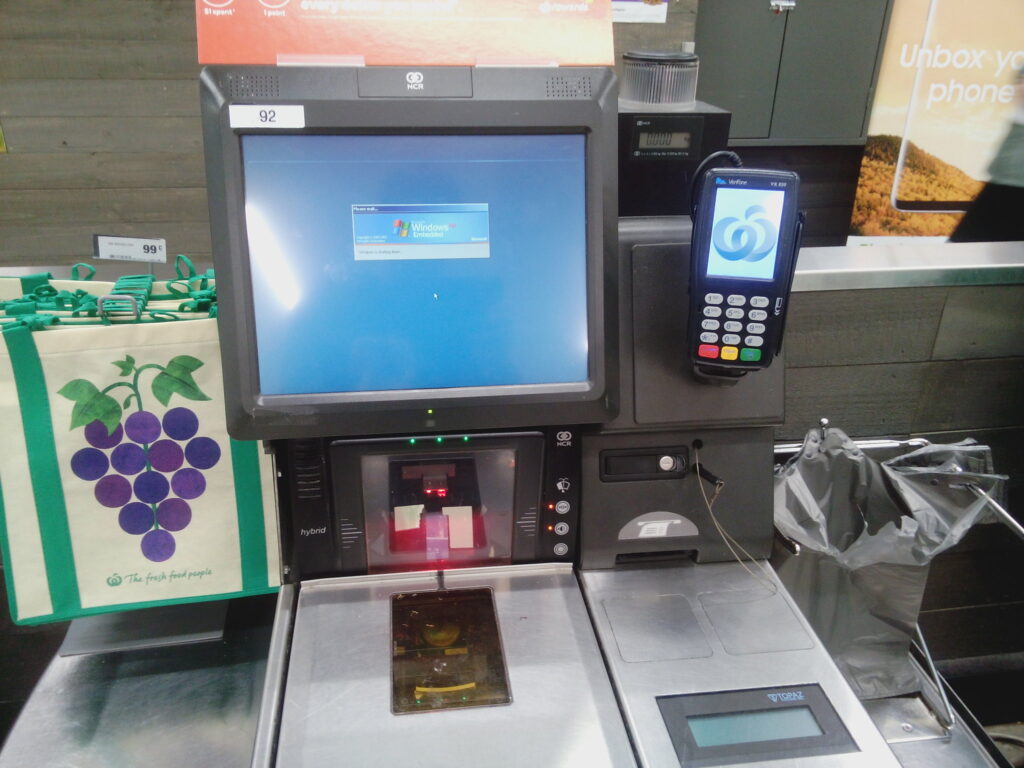

Automation: how to eliminate employees and annoy customers

There’s a massive technology industry — both big old tech companies and startups alike — dedicated to the idea that all humans must be eliminated. This is automation, and it the one religion that unites diverse businesspeople everywhere.

Sometimes automation makes things better. GPS is better than maps from gas stations. Bar code scanners make grocery checkout faster and more accurate than the checkers of yesteryear who had to punch prices in manually.

But the first question that businesses ask when faced with automation is not “Will this make things faster, better, or more accurate?” They ask “Will this eliminate a worker?” If it will, and if it functions (even if barely), then business adopts it.

Is self-checkout at the drugstore faster or more accurate? No. It is more tedious to check out your own stuff. There is the little camera implying that you are probably going to steal things if we don’t keep an eye on you. If you don’t put things in the bagging area the right way, you get an error. We need to send somebody over if you buy something too expensive or something that only people over 18 should buy — even if, like me, you’re obviously an awful lot older than 18.

You have to figure out how to pump your own gas at the automated machine. I’m not better at that than the gas pump jockeys were, but there is no choice. My mom, age 89, doesn’t really want to learn to pump her own gas — so her kids have to fill up her tank for her.

When you call for customer service, you have to navigate the voice-mail tree and evade the options that will just give you an automated report (if that’s what you want, you probably already checked it online). If you go to leave a complaint about a company on its website, a chatbot tries (and usually fails) to answer your question.

Now we’re getting self-driving cars. Sure, they sometimes drive into wet cement and they occasionally hit the brakes for no reason, causing accidents, but if we can eliminate a human, we have to do so.

The latest “innovation,” according to the Washington Post, is Google’s attempt to replace audiobook narrators with a synthetic voice called “Archie.” Archie will never miss a word or read a question as a statement. But Archie also won’t capture the excitement of the hero’s close escape from doom or the dread of the entrepreneur in the business narrative who has just realized he can’t make payroll.

The traditional response to these complaints is two-fold. First, according to Clayton Christensen’s classic disruption theory, lame, cheap down-market solutions will eventually move upmarket and get better. (Really? Is that self-checkout any better than it was five years ago?) And second, consumers interacting with machines and having a poor experience will find alternatives where they get to deal with people instead. Except they don’t. Are you going to a drugstore with human checkout or the one that takes your insurance and allows you to renew prescriptions on an app? Human-moderated experiences are not only generally more expensive, they’re rarer.

What can you do?

If you’re in a company making decisions, don’t just ask if automation can eliminate a job. Ask if it will actually make things better for the customer. Push back if it can’t.

And if you’re a consumer, interact with humans — restaurant servers, cashiers, service people, craftspeople, editors, and designers, for example — and enjoy the process. Smile. Shake hands. Thank them. And tell them you value their work.

We may not be able to stop the mindless march to automation, but at least we can try to slow it down.

News for authors and others who think

According to Alex Reisner in The Atlantic, many of the large AI models were trained on a corpus of text called Books3 including more than 150,000 stolen copyrighted books. This is a lot clearer version of copyright theft than it appeared, and may seriously kneecap the legal position of tools like Meta’s LLaMA.

In the “any verb can be nouned” department, The New Yorker documented a language trend: the “ification” of almost everything. My favorite coinage: ‘alternative facts’-ification.

Jane Friedman theorizes that the onslaught of AI-generated crap books may cause Amazon to crack down on all self-published books where Amazon itself supplies the ISBN. That would be the simplest automated solution — and would put a serious kink in the self-publishing model.

Three people to follow

Michelle Garrett for her intelligent commentary about PR and freelance life.

Ronan Farrow, who keeps exposing unspoken but profound truths in The New Yorker. His latest target: Elon Musk.

Douglas Burdett of The Marketing Book Podcast, the most diligent and intelligent interviewer in the book business.

Three books to read

The End of Reality: How Four Billionaires are Selling a Fantasy Future of the Metaverse, Mars, and Crypto by Jonathan Taplin (Public Affairs, 2023). Peter Thiel, Mark Zuckerberg, Marc Andreesen, and Elon Musk are selling you a corrupt version of the future built on crypto, the metaverse, and all the other buzzy buzzwords.

Social Media and the Public Interest: Media Regulation in the Disinformation Age by Philip M Napoli (Columbia University Press, 2019). Still the smartest book about what government can do about ethically bankrupt social media sites.

A Beautiful Constraint: How To Transform Your Limitations Into Advantages, and Why It’s Everyone’s Business by Adam Morgan & Mark Barde (Wiley, 2015). Stop thinking of limits as a problem and start thinking of them as an opportunity.

Plugliness

Just follow my blog. New thinking every weekday. Subscribe already.