New voting systems would benefit moderates, according to this voting simulation

The average American politician is far more extreme than the average American voter. Our current voting methods encourage these extreme viewpoints. To investigate how new voting systems like ranked choice voting and “jungle primaries” could change this, I created a simulation of different voting systems and tested it on various types of voting districts.

How the simulation works

The simulation models 1000 voters in a district. It is simplified, and therefore not completely realistic, but it is quite revealing. (As the statistician George E.P. Box said, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.”)

The simulation makes the following simplifying assumptions:

- All voters in a district are at some point on a linear ideological scale from liberal to conservative.

- All candidates fall on the same scale.

- All voters vote in all elections.

- When voting in an election where there are not choices between parties, voters will vote for the candidate closest to their own ideological position.

- When voting in an election that requires choices between parties, voters may vote either on party lines, or along ideological lines (I modeled both).

- Voters determine party affiliation by their ideological position — left-of-center voters are Democrats, and right-of-center voters are Republicans.

The ideological scale I used puts the center of the nation at zero, with more liberal voters and candidates to the left, and more conservative voters and candidates to the right. The units are arbitrary, but I use a system where a value of, say, 1.5 indicates 1.5 standard deviations in a conservative direction (right) of the national mean.

I simulated two districts — one with a mean of 0.1 units to the left and one with a mean of 1.0 units right. Voters are distributed along the ideological continuum on a (normal) bell curve centered on the mean with a standard deviation of 1.0 units. I also simulated a third district with left-leaning majority combined with a far-right minority.

Each of the simulations includes four candidates.

- Priscilla Progressive is 2.0 units to the left (liberal) side of average. Think Bernie Sanders.

- Linda Liberal is a moderate liberal, 0.2 standard deviations to the left of average. Think Kyrsten Sinema.

- Connie Conservative is a moderate conservative, 0.2 standard deviations to the right of average. Think Susan Collins.

- Robbie Righteous is 2.0 units to the right (conservative) side of average. Think Ted Cruz.

None of these assumptions is completely accurate in practice. In reality, not everyone votes in every election, nor do they vote rationally, nor do they vote based solely on ideological position, nor is it fair to characterize them solely by a single ideological position. And I have put every voter into one of two parties, ignoring independents.

But for the purposes of benchmarking voting systems, these simulations reveal useful things about the differences in ways to resolve elections.

In the Azure (light blue) district, all voting systems yield similar results

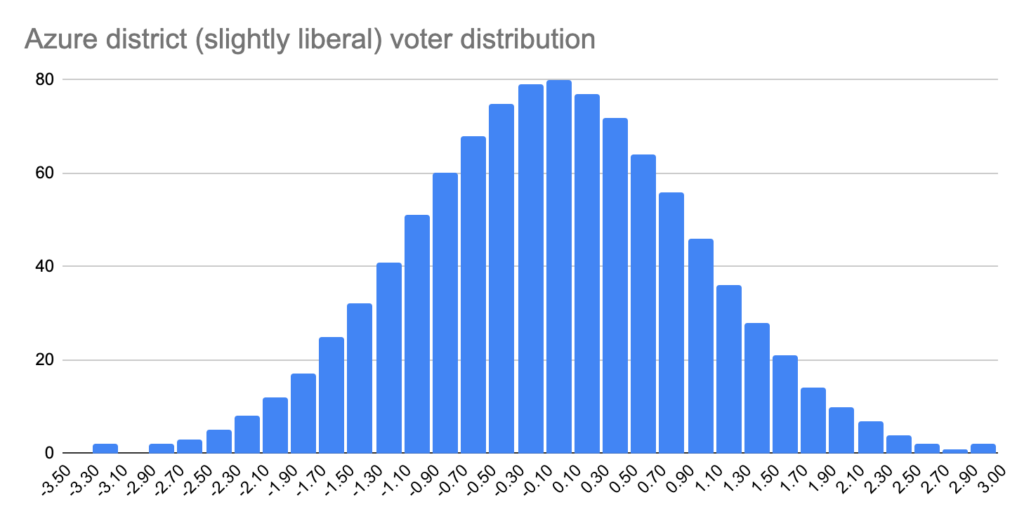

Here’s the distribution of voters in the Azure district, which has a mean of -0.1 units (slightly to the left of the population average of zero) and a standard deviation of 1.0.

In this centrist and well-balanced district, all the voting systems generated the same result.

Of the 1000 voters in this ideal district, 520 are Democrats and 480 are Republicans. Their distribution causes them to be more likely to vote for more centrist candidates. In the Democratic primary, the results are:

- Priscilla Progressive: 147

- Linda Liberal: 373

In the Republican primary, the results are:

- Connie Conservative: 355

- Robbie Righteous: 125

When Linda Liberal faces off against Connie Conservative in the general election, if voters vote along party lines, Linda Liberal wins, 520 to 480. If they vote along ideological lines, which allows people to cross party lines, the result is exactly the same.

What about more interesting voting systems?

In ranked choice voting, voters select a first, second, third, and fourth choice. In each round of counting, candidates at the bottom are eliminated, and their second places votes allocated to the other candidates. What happens in a ranked-choice election in the Azure district, assuming voters rank the candidates by how far they are from the voter’s own ideological position?

Here are the results of first place votes in the first round:

- Priscilla Progressive: 147

- Linda Liberal: 373

- Connie Conservative: 355

- Robbie Righteous: 125

After eliminating fourth-place candidate Robbie Righteous and reallocating his votes to their second-place choices, here’s the result in the second round:

- Priscilla Progressive: 147

- Linda Liberal: 373

- Connie Conservative: 480

So Connie Conservative has picked up all the votes from Robbie Righteous voters. But now we have to eliminate the weakest remaining candidate, Priscilla Progressive. In the final round, the results are as follows:

- Linda Liberal: 520

- Connie Conservative: 480

Linda Liberal wins, as she picks up all the second-place votes from Priscilla Progressive voters.

Finally, let’s look at a “jungle primary,” also known as a blanket primary. In this system, all the candidates from all parties run in a single primary. The top two finishers then compete in a runoff to determine who wins. Jungle primaries are particularly helpful in districts where one party dominates, since they ensure that the winners of a party primary don’t just skate into a general election without opposition.

In the Azure district jungle primary, the votes are distributed just the same way as in the ranked choice election, because everyone votes on ideological lines for the candidate closest to their views:

- Priscilla Progressive: 147

- Linda Liberal: 373

- Connie Conservative: 355

- Robbie Righteous: 125

In the general election runoff, the two leading candidates, Linda Liberal and Connie Conservative, face off. And of course, given that it’s a slightly left-leaning district, Linda Liberal wins by the predictable margin.

- Linda Liberal: 520

- Connie Conservative: 480

At this point you are likely thinking, why bother with all these exotic voting systems? They seem to yield the same result. And indeed, in a balanced district like the Azure district, they do. That’s reassuring in a way — the voting systems shouldn’t cough up weird results in a normal district.

But in a more skewed district, the different voting systems do deliver different results — results that tend to favor more centrist candidates.

In the Crimson district, extreme conservatives win in traditional elections, but moderate conservatives win with more innovative voting systems

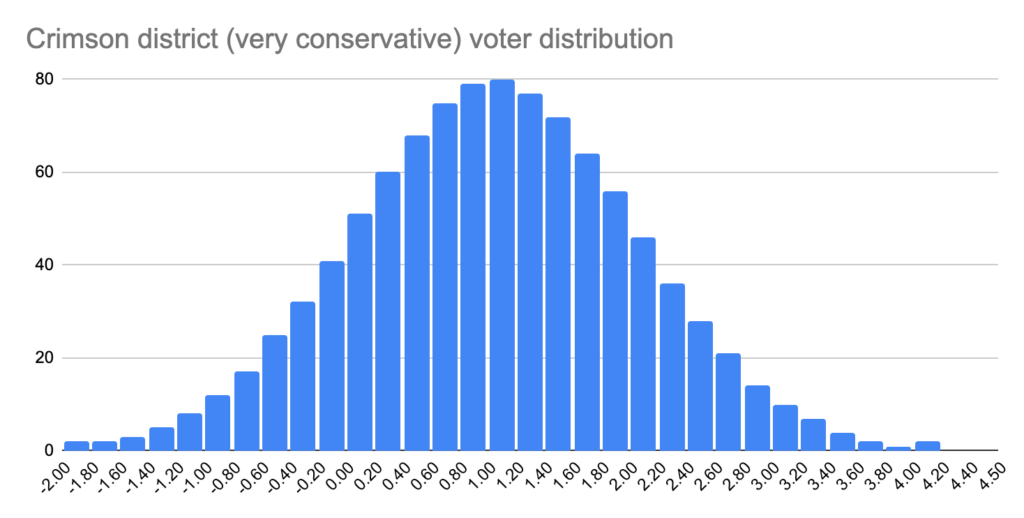

Now let’s consider a district where the voters are far more likely to be at an extreme position on the ideological scale. In the Crimson district, the average voter is 1.0 units further to the right than the country as a whole. The standard deviation remains one unit.

In a traditional election in this district, what matters most is the Republican primary. And of course, the more extreme candidate, Robbie Righteous, wins that primary:

- Connie Conservative: 373

- Robbie Righteous: 480

If voters vote along party lines in the general election, the 853 Republicans in the district will sweep Robbie Righteous into office; Linda Liberal, winner of the Democratic primary, will only get 147 votes. If, in the general election, voters instead vote on ideological lines for the candidate closest to their position, some Republicans will vote for Linda Liberal, finding her more palatable than the extreme Robbie Righteous, but Robbie Righteous will still win, 560 votes to 440 votes.

This is in some sense a perverse result, because the candidate closest to the mean voter in the Crimson district is not Robbie Righteous, but the less extreme Connie Conservative. In a way, the primary victory of Robbie Righteous has robbed the bulk of moderately conservative voters in the district from getting the candidate closest to their position.

The other voting systems cure this problem. In ranked choice voting, it looks like this in the first round:

- Priscilla Progressive: 16

- Linda Liberal: 131

- Connie Conservative: 373

- Robbie Righteous: 480

Since Priscilla Progressive doesn’t stand a chance in this district, we reallocate her votes. And after the second round, we reallocate votes from Linda Liberal. In the final round of the ranked choice vote, the results are as follows:

- Connie Conservative: 520

- Robbie Righteous: 480

Connie Conservative has picked up all the votes from liberal voters who find her preferable to the extreme candidate Robbie Righteous. So Connie Conservative prevails. Ranked choice favors the moderate in a way that the primary party system doesn’t.

A similar outcome happens in the jungle primary. The two candidates who remain after the first round are Connie Conservative and Robbie Righteous. And when those are the two choices, Connie Conservative wins.

So ranked-choice voting and jungle primaries mitigate the power of extreme voters that carried far-right candidate Robbie Righteous to victory in the traditional primary system. The more moderate candidate, who is more representative of the population’s average position, wins.

In a bimodal district, innovative voting systems again mitigate the power of extreme voters

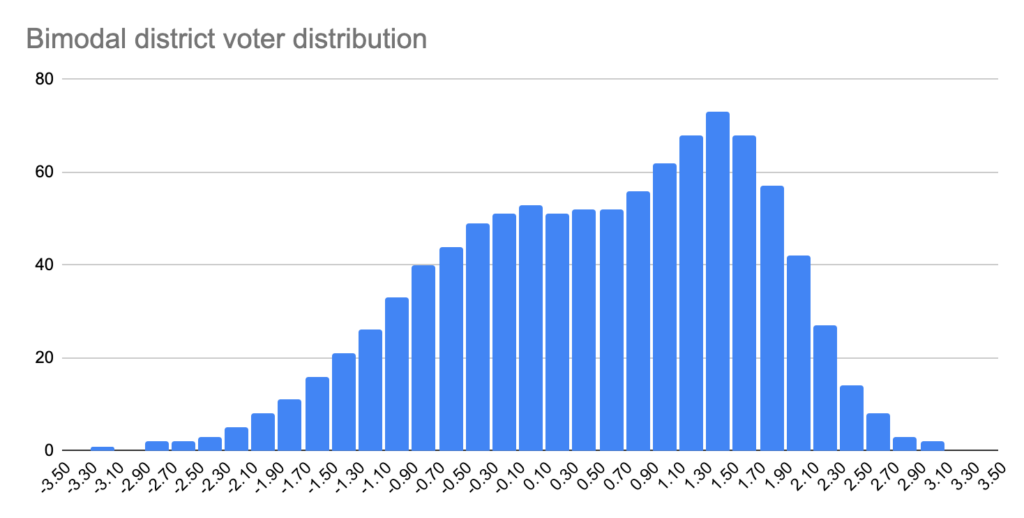

In American politics these days, the Trump wing of the Republican party dominates the party. A voting district that reflects this might have a normal distribution of voters overlaid with a smaller collection of more extreme voters — a distribution that also might arise in a gerrymandered district that brings together two highly different groups of voters. How would different voting systems address this phenomenon?

To see, I created a district with 650 voters who are slightly liberal, like the Azure district, and 350 voters who are more extreme. The extreme group has a mean of 1.5 units to the right of average, and a more tightly bunched standard deviation of only 0.5 units. The distribution is “bimodal” because it has two peaks (statistically, “modes”) representing the two voter collections.

As in the Crimson district, traditional voting favors the extreme candidates, and the more innovative voting systems favor the more moderate candidates.

This district includes 338 Democrats and 662 Republicans. Linda Liberal wins the Democratic primary, since she’s closer to the average positions of the Democratic voters. But the far-right group propels Robbie Righteous to victory in the Republican primary, 362 to 300.

In the general election, the Republican Robbie Righteous wins if people vote on party lines. But if they vote on ideological lines, Linda Liberal wins, since she is closer to the center of the opinions of the whole district. Regrettably, in today’s voting environment, voters are more likely to vote by party in the general election, fearing what would happen if, as Republicans, they send a Democrat to a narrowly balanced Congress (or vice versa). In an election for a local office such as governor, where parties are less important, Linda Liberal might win this district over an extreme opponent like Robbie Righteous.

Ranked choice voting yields interesting results in the bimodal district. Here are the results in the first round:

- Priscilla Progressive: 94

- Linda Liberal: 244

- Connie Conservative: 300

- Robbie Righteous: 362

Priscilla Progressive is too extreme for this conservative-skewing district, so her votes get reallocated — predictably, to Linda Liberal. The second round looks like this:

- Linda Liberal: 338

- Connie Conservative: 300

- Robbie Righteous: 362

The leaders are the candidates at the center of the two peaks in the bimodal distribution– one moderately liberal (Linda Liberal) and the other extremely conservative (Robbie Righteous). Connie Conservative is less appealing, falling between the two peaks. So her votes get redistributed. And there’s a surprising result in the final round:

- Linda Liberal: 576

- Robbie Righteous: 424

Linda Liberal wins this district, even though the district contains far more Republicans than Democrats. If you are a party loyalist, this seems wrong. But when you look at the ideology of the district as a whole, it’s fair. Linda Liberal is the popular candidate closest to the center of the distribution, and Robbie Righteous is too extreme for the bulk of the voters in the district. Linda Liberal is acceptable as the second or third choice of the voters who are not at the extreme right, so she wins.

What happens in the jungle primary in this district? Here, the two highest vote getters are the two conservatives:

- Priscilla Progressive: 94

- Linda Liberal: 244

- Connie Conservative: 300

- Robbie Righteous: 362

So the general election pits Connie Conservative against Robbie Righteous. And with the help of the voters left of center who no longer have a liberal to vote for, Connie Conservative wins soundly:

- Connie Conservative: 638

- Robbie Righteous: 362

The two more modern voting systems give different results. But they favor the moderate candidates, Linda Liberal and Connie Conservative, over the more extreme Robbie Righteous who only appeals to a minority of voters.

These election systems could save America

This model is clearly not fully representative of how people actually vote. But it does reflect some modern realities of voting in America. Extreme candidates can dominate a primary election, and then party-line voting causes them to win the general election. And this a particular problem in districts that are shifted far from the center, like the Crimson district, or where a sizable minority has a more extreme viewpoint, like the Bimodal district.

It’s interesting to me that relatively moderate Republican candidates like Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski can win in states with ranked choice voting (Maine and Alaska) or jungle primaries (Alaska). These systems diminish the influence of parties and disadvantage extreme candidates whose appeal is greatest within partisan primaries.

Voters may be swinging back to the concept of moderate candidates as a backlash to the polarizing extremes of the last few election cycles. It’s notable that Democrats nominated Charlie Crist, a former Republican, to run against the far-right Republican incumbent Ron DeSantis in the election for Florida governor. And in Massachusetts, the moderate Republican governor, Charlie Baker, won two elections in an overwhelmingly Democratic state. If Republicans in Massachusetts nominate far-right candidate Geoff Diehl in this election cycle, he’s almost certain to lose to the Democrat, Maura Healey.

If the only alternative to an extreme candidate you don’t like is an extreme candidate pulling further in your own direction, we’re unlikely to end up in a place where America can continue to be governed in a rational way. We’ll just swing from political pole to political pole depending on who wins the tug of war that day. That’s not stable. But alternate voting systems like the ones I’ve simulated here could allow moderates to generate appeal for the mass at the center of the electorate, diminish the pull and influence of parties, and maybe even knit America together again.

I don’t claim to be a mathematician, but I’m curious about why Connie Conservative picked up 22 of Robbie Righteous’s votes in the ranked system. Why would people who voted for him under the current system change their minds in a ranked one when presented with the same candidates????

You detected a bug in my model. I’ve fixed it now and the numbers should reflect that. The number of votes that Robbie Righteous gets is the same in the first round under both systems.

Ah, the HAG Theory pops up again. The A stands for Ken Arrow who applied the underlying principles to voting systems. The theory also explains why gerrymandering is, amongst other interesting results.

Unfortunately, all systems have defects that cannot be corrected for all circumstances, leading to whacky results, despite the bias built into the system.

It is fine to recommend changes to systems, but everyone needs to know the above paragraph.

I’m betting that if everyone votes based on where they and the candidates are on a continuum, those contradictions don’t come up in the same way.

That may not be the real world, but it is a valuable way to understand it. All models are wrong . . . but some are useful.

In my view the main issue is the primary approach. A small minority of highly motivated people vote in these elections and that tends to favor extreme position candidates. It is almost never a cross section of voters, let alone all.

I like the more all-in approaches but I think it’s also true that ranked choice and what you call jungle voting tends towards the common denominator candidate. That’s fine if you favor the status quo. If you’re looking for change, however, you will be disappointed.