Mary Norris, Comma Queen, and my fraught love for copyeditors

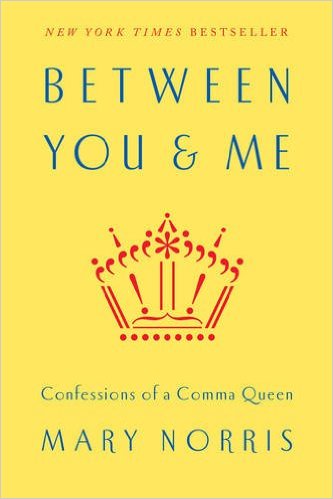

I vastly enjoyed Between You and Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen, the memoir of New Yorker copyeditor Mary Norris.

I vastly enjoyed Between You and Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen, the memoir of New Yorker copyeditor Mary Norris.

The pas de deux that the writer and editor dance together is lively and invigorating, because both want nothing more than for the writing to be perfect. But it’s a fraught affair, because your partner’s job is to be a nag. The challenge is in deciding what is perfect. As Norris writes:

. . . [G]ood writers have a reason for doing the things they way they do them, and if you tinker with their work, taking it upon yourself to neutralize a slightly eccentric usage or zap a comma or sharpen the emphasis of something that the writer was deliberately keeping obscure, you are not helping. In my experience, the really great writers enjoy the editorial process. They weight queries, and they accept or reject them for good reasons. They are not defensive. The whole point of having things read before publication is to test their effect on a general reader. You want to make sure when you go out there that the tag on the back of your collar isn’t poking up — unless, of course, you are deliberately wearing your clothes inside out.

And, like me, the New Yorker is willing to embrace the occasional obscene word. So I loved this:

My colleagues and I have argued in the office over whether it should be rendered F-word, F word, “F” word, or “f” word, bu twho really gives a fuck about the proper form of a euphemism?

Any book with an erudite chapter on the history and variations of the singular they gets my vote. We don’t agree on everything — New Yorker style prefers “copy editor” to “copyeditor,” for example — but that’s what makes it interesting.

I have just completed reviewing the copy edits on my own book. Each one bothered me. In each case I had to ask myself “Why do they think it is better that way?” and try to justify my own usage, if I wanted to keep it. (And despite my use of the genderless “they,” it’s nearly always a “she” that I’m having my virtual argument with.) I preserved a few of my commas, my uses of “they,” and all of my numerals (it’s “26%,” dammit, not “twenty-six per cent”), but thank God she caught my misspelling of Sergey (Brin).

To most authors, copyeditors are just faceless machines that spits back prose with niggling corrections. But I’ve had the pleasure of collaborating with copyeditors at my job and learned to love their passion, their persistence, and their indefatigable optimism about language. So it sort of amused me that in my manuscript, when I suggested that you should reward good copyeditors, preferably with chocolate, my own copyeditor commented “You must be very popular.” I smiled because it confirmed that there was human on the other side of that computer screen.

Here’s the human who wrote Between You and Me, speaking at TED. She sounds just as I pictured her.

A comma story, as related by my husband.

Once upon a time there was a young 1st year psych major taking his obligatory English 101 class. Like many smart and brash young men, he did not pay attention in his high school English classes. His English 101 Prof stressed the importance of proper punctuation in writing assignments. Realizing his weakness, and still being a brash young man, he handed in his paper with a long string of commas at the beginning. These were accompanied by a parenthetical note: (I have no idea where they go, so here are a whole bunch – you put them where you want them!)