Killing widows and orphans, and other lost skills

I’ve got a long history in the print business. I’ve got detailed knowledge of an obsolescing technology. I can’t help but wonder what that means.

Ink is in my blood. My grandfather was a linotype operator for the long-gone Philadelphia Bulletin (an afternoon paper); he worked with hot lead and his hands were so tough he could pick up a hot potato and not feel it. While I didn’t work with lead, I did the next best thing — I set type (digitally) and did pasteup for the program book of the World Science Fiction Convention, Noreascon Two, in 1979. In the startups I worked at in the eighties and nineties, it wasn’t enough to work with words; I had to work with designers and printers, too, because we were actually making things: boxes, manuals, diskettes with stickers on them, Tyvek envelopes, and bound four-color printed textbooks. I’ve bought millions of dollars worth of that stuff.

I worked at the frontier of digital publishing and my all-digital operation became a significant advantage for the textbook company I worked for. But somewhere, there was always a machine making things.

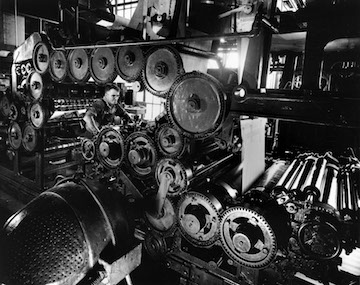

I’ve spent plenty of time “on press” — dwarfed by the massive, clanking, churning machines on all sides, like a kid surrounded by a lot full of school buses. They took rolls of paper the size of sumo wrestlers, printed them, and turned them into the folded “signatures” that get bound into books. I’ve given the thumbs down when the color isn’t quite right and watched the ink-stained pressmen — and yes, they were all men — baby, persuade, and tweak those leviathans until the colors and the pages were what they ought to be. I was in awe of their knowledge.

It’s loud and busy in the press room. It’s smells of fresh ink and lubricating grease (and I still get a flashback when I hold something freshly printed, damp and fragrant, in my hand). You had to stand your ground with those guys, but when it came out right and you saw those sheets and pages and books coming off the line, everybody smiled, because we know that we had worked together and made something useful.

Those skills are not obsolete. On my most recent book, I was the publisher, not just the coauthor — I chose the materials, managed the layout process, worked with the artists who did the color separations for the photo on the cover, approved the proofs, arranged for the warehousing and shipping. (I didn’t go on press; our publishing partner never understood why I wanted to.) Forrester Research is a digital business that sells ideas, but for a little while we built books, owned inventory, generated profits from people buying bound rectangles made of paper and buckram and board. I loved every page, because I knew it was right; the words, the look, the knowledge, the feel, the whole damn package.

I’ve been surprised, this week, to find those skills still worth something. As I look at the page proofs of Writing Without Bullshit, I wrinkle my nose every once in a while as I see a font gone awry, an awkwardly placed graphic, an unevenly typeset table, an orphan, or a widow. (A orphan, as anyone with a typesetting or layout background will tell you, is a single word that ends up on a line of its own at the end of a paragraph, while a widow is a single line that ends up spilling onto the next page. Widows and orphans interfere with the flow of reading, tripping the reader up like an uneven step in a staircase. You must have no mercy; you have to kill them.)

The same skills have come up as I’ve managed the design of my first report on The State of Business Writing (copies coming this summer, unless you’re at my workshop at the Content Marketing Conference next week). Designs that looked great on screen seemed a bit tight on the proof, because printing is an analog thing — sometimes the staples don’t land right in the middle, the page gets trimmed a half-millimeter off, or the gutter that seemed adequate on the screen isn’t quite right when you hold it in your hand.

The irony is not lost on me: that my report and my book — my printed report and book — are about how to write for people who read on-screen. A lot of effort now goes into making on-screen reading better, even as media sites continue to create ad formats that make it worse. We haven’t mastered the digital equivalent of killing widows and orphans.

But I still know how to kill them in print.

I remember my grandfather, retired, reading the newspaper, grimacing and scoffing about the horrible way that computers typeset the news. Linotype operators knew enough to break “forecast” between the e and the c, but the computers didn’t. Progress? Harumph.

Is that me? Am I destined to be a curmudgeon as I extinguish widows and orphans that nobody cares about any longer? But I know that if you read my book, you’ll probably be reading it in print. So I’ll keep killing those widows and orphans as long as I can. I’m doing it for you.

Orphans and widows… These things have always bothered me when I write or review documents and I always thought it’s because I’m slightly OCD; I didn’t realize they’re an actual thing. I’m glad to know how to call them now! Thank you for sharing.

I loved working in printing and miss it tremendously! It was so much fun to go “on press” and manipulate color until it was exactly right. Thank you for the flashback!

One thing I noted at the beginning of this article is the use of “I’ve got.” I would have thought you’d use “I have.” “I’ve got” has proliferated our everyday speech but I detest it! Please, Josh, don’t succumb!

I worked in print for many years. I cringe when I see page layouts run amok or awkward typesetting in either print or online. I’ve re-written lines many times to make them fit better on the page.

BTW, when you get a new book, the first thing you do is open it (gently) and smell the ink and paper. Right?

I recently walked by the Chieftain newspaper in Pueblo, Colorado, and caught a whiff of ink. It brought me back to those days when the newsroom and the pressroom were in the same building.

I read all my books on Kindle. But I will buy your hard copy, thanks to this wonderfully nostalgic column.

I too started in the print world, working at a university press. That’s where I learned the value of great writing and thoughtful design, both skills that serve well no matter the medium. One of the journals I managed was printed on hot metal, and I still remember how the pages felt, the slight impression you could feel on all the words.

Sigh, times gone by… Glad you got to revisit the experience with your book!