Julia Roberts’ holes — a musing on the cost of early carelessness and late edits

The local paper of Jamestown, New York, The Post-Journal, has now revealed that 51-year-old actress Julia Roberts’ aging holes are doing well. Up close and personal is fine for a profile, but this closeup seems a bit extreme. Even so, it made me think about how many more mistakes we see these days, and why.

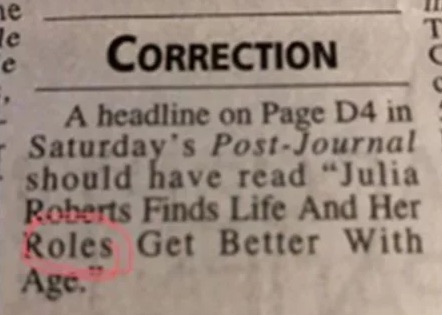

Here’s what readers saw:

The original AP story, of course, is about Julia Roberts’ roles. Although, judging from what I’m hearing from my dentist, my otolaryngologist, my urologist, and my gastroenterologist, if she actually has any holey health secrets I want to know what they are.

Naturally, the paper published a correction.

Hey, I’m sure they corrected it online. (Although I can’t find it in the post-journal.com site any more . . . I wonder why?) So why does it matter if we print mistakes now?

Write first, fix later

The traditional writing cycle used to look like this:

Write

Edit

Rewrite

Perfect

Proofread

Publish

This cycle was honed in the days where making revisions was expensive. And as long as publishing has existed, one fact has been true: the later in the process that you correct a mistake, the more expensive it is (and the greater the chance that you inadvertently create another error). So for books, magazines, and newspapers, editing before publishing was essential.

Because I was a writer, editor, and publisher in an earlier life, I can tell you what once would have happened with something like this. Layout people would paste this stuff up to make a page image. Somebody would proofread that (and hopefully find the error). They’d then photograph the page to turn it into a printing plate. If someone noticed the error in the photo impression, they might even fix it with a razor blade, or they might take a new photograph. And if an error like this got into print, somebody would get fired.

Now the page layout and headlines person puts this into a page layout program and the results start coming off the presses and going up online. There’s not as much revenue going around, so the proofreader, if there is one, is probably overworked and underpaid.

Today’s writing cycle tends to look more like this:

Write

Rewrite (optional)

Publish

Promote

Perfect (optional)

Why worry about errors if you can fix it afterwards?

(And yes, given the number of typos that make it through in this blog, I am just as guilty as the next person.)

It’s not just text. The same process applies to code, where you’re supposed to distribute a “minimum viable product,” see how people react, and then fix the bugs. When we were shipping software on diskettes, bugs in shipping products were mortifying. Now they’re just part of the process.

Seth Godin even shrugged it off when copies of his new marketing book started shipping with pages upside down.

And our president can’t be bothered to correct his spelling when he’s ranting about “smocking guns.”

“Democrats can’t find a Smocking Gun tying the Trump campaign to Russia after James Comey’s testimony. No Smocking Gun…No Collusion.” @FoxNews That’s because there was NO COLLUSION. So now the Dems go to a simple private transaction, wrongly call it a campaign contribution,…

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 10, 2018

But here’s something to know about writing: it actually improves when you work on it. If you want to escape writer’s block, remember that shitty first drafts are way better than nothing. The second draft can be better than the first draft, especially if you have some feedback from an editor. And as you get towards the end and closer to publishing, you should keep the changes small and minor. Making big changes (in writing or in software) at the end significantly increases the chances that you will soon suffer your own “Julia Roberts’ holes” moment.

This is why, on the last book I collaborated on, I had a huge fit when my coauthor substituted a page and a half of new text for a paragraph in the final draft, just before the book was set to go to copy edit. It wasn’t about the quality of what he wrote, it was about the risk he was taking. (The fact that it happened when I was on vacation on a mountain in Vermont and hadn’t budgeted time to review new material had nothing to do with it. Well, maybe a little.)

Speed to publish is a competitive imperative in today’s world. But quality requires moving steadily towards perfection, not publishing first drafts. When you’ve completed something, you’re not done. Keep making it better. And when it’s time to publish it, do what you can to make sure it’s perfect.

[Currently hunkering down waiting for you all to point out all my typos.]

I understand the MVP mindset and even teach Reis’ book at ASU.

Still, an MVP doesn’t work for every product. Cars, airplanes, and pharmaceuticals quickly come to mind. We don’t want to fix those planes while they are in the air.

It’s unfortunate that speed kills today—quality often be damned. Still, I’m curious. I’d love to see some data on mistakes now vs. two decades ago. Has the percentage of errors increased? Or do big ones just get a good deal of publicity like this one?

https://slackiebrown.com/fuck-face-story-behind-billy-ripkens-legendary-fleer-baseball-card/

Reminds me of the ancient joke —

CORRECTION

~~~~~~~~~~

An article in yesterday’s Chronicle referred to Mr. John Jones as “a defective on the police force.” This, of course, was an error. Mr. Jones is in fact a detective on the police farce.

I absolutely love this post, Josh. There’s something to be said about speed in today’s fast and furious authoring process, but sloppiness is not a substitute for solicitude. Ironically, I was just reading a different article about Julia Roberts yesterday… guess I should go back and see what typos it contains. 🙂

Great post, Josh. I worry about this whenever I tell people to write the ugly first draft first. The Publish button is so tempting. But newspapers should have processes to protect against egregious errors, even when working on deadlines.

A few typos are inevitable in an imperfect world. Egregious typos betray a failed process.