How Zoom is reclaiming its brand . . . and why it will succeed

Zoom is the easiest to use of all videoconferencing systems, but its security was questionable. After two weeks of spectacular advances, it’s now on a path not only to fix its security, but to restore its brand.

Zoom surged in popularity because it was easy to use for both novices and experts in a variety of formats and on a variety of devices. That success brought scrutiny, and revealed questionable security practices. Zoom’s CEO Eric S. Yuan promised to fix things.

If you follow the rise and fall of technology companies, you’ve heard this story before. Company is revealed to be behaving badly. Company vows to fix things. Often, somebody senior gets fired. And then, everybody in the company and outside just keeps doing what they were doing before. Nothing much actually changes. (That’s pretty much what’s going on at Facebook, from my perspective.)

For me to believe Zoom isn’t like all those other companies, I’d have to believe two connected things. First, that Zoom could actually change its culture. And second, that it could restore its brand at the same time.

This post explains why I believe both those things are happening.

Zoom’s problem was different

Facebook makes money from ads. It believes that the more of your data it has, the more successful it will be. Privacy is a source of friction, not a goal. This is why I don’t believe Facebook’s culture will ever change.

Zoom, on the other hand, does not take ads. It succeeds based on the satisfaction of customers who pay for its service. To be successful, it has to be awesome. Privacy and security are part of being awesome, not an impediment.

Why did Zoom go wrong? Clearly, its engineers prioritized the customer experience over all else. If it can keep a little server on your machine, even if you are not a subscriber, then it can start quicker. Better experience! If you can join a meeting quickly with your camera on, the meetings start better. Better experience! If it can route traffic through China when there is congestion elsewhere, you’re less likely to have a video glitch. Better experience again.

Of course, all of these choices that Zoom’s engineers made had negative consequences. The culture appeared to be, “Make it work great, and we’ll fix the security and privacy stuff if it’s a problem.”

Well, it was a problem. Like many Silicon Valley companies, Zoom got ahead by making things easier for users and breaking rules its competitors abided by. The question now is, can Zoom fix the problems (and the culture) and stay easy to use?

How Zoom is fixing everything

The speed with which Zoom followed through on its commitment to fix the security problems is breathtaking. (And remember, just like you, Zoom’s management and engineers are doing this while working from home with all the distractions that entails.)

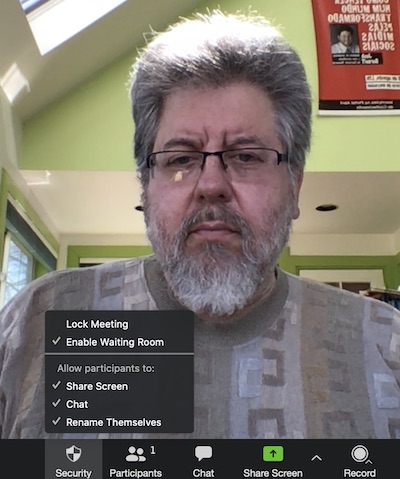

In addition to just fixing things that were wrong, Zoom implemented security fixes in its own inimitable way — with a better interface. For example, I recently ran a public Zoom meeting, just the sort of meeting that is sometimes subject to “Zoombombing” (trolls joining the meeting and disrupting it with offensive audio or video). But there is a new feature on the Zoom control bar — a security icon.

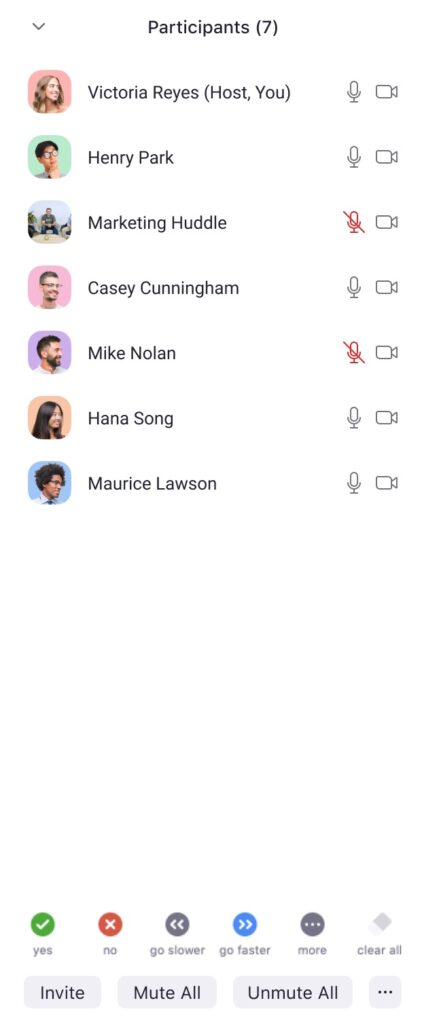

When you click on the security icon, you can set up your meeting so that new participants have to wait in a waiting room, and you can prevent participants from sharing their screen or chatting. You can prevent new participants from entering by locking the meeting.

You also have new tools to manage participants. In the same space where you admit people from a waiting room, you can easily mute them individually or all at once.

There are a number of other technical changes. For example, all meetings now require passwords, but if you share the meeting in a scheduling application, the password is incorporated into the invitation, so you can still get in with one click. And the meeting ID is no longer displayed during meetings, which makes it harder for people to identify it, share it, and invite disruptors to the meeting.

The CEO has conducted “ask-me-anything” meetings to answer questions from security pros, addressed critical accounts from academics, and changed its governance to include respected security advisors.

My experience as an analyst covering technology companies tells me that this is not a typical response. It’s not lip service. It’s cultural change, generated from the top, with actual product engineering changes to match. Zoom is not standing still, it’s not just defending itself with empty statements, it’s actually engaging with critics and re-engineering both the product and the company to be more respectful of security — and doing all of this, while dealing with a massive traffic increase, a massive increase in public scrutiny, and a lockdown that affects everybody’s productivity.

This is not business as usual.

What about the brand?

As Zoom’s example shows, you build a brand in years and damage it in a day.

But the damage doesn’t have to be permanent. (Do you still take Tylenol?)

To rebuild the brand, you must do all of these things:

- Admit the problem.

- Describe how you will fix the problem, even if the fix is painful.

- Follow through and fix the problem.

- Continue to message about normal features along with the fixes.

- Maintain a focus on the customer throughout.

- Avoid relapses — additional problems like the first one.

Zoom is doing all of these things. Of course, we have to wait and see what happens with the last one.

Where will Zoom’s brand be a year from now?

It will still be the easiest possible choice for videoconferencing.

It will have the largest market share, although that share will have declined a bit.

One by one, security people will change their minds, assuming the company continues to follow through. There will be positive accounts of the recovery to go along with the negative accounts we’ve already read.

And the company may be in a position to get back to thinking big about the next steps for virtual meetings, like augmented reality, joining meetings from autonomous cars, or enabling videoconferencing with minimal hardware and low bandwidth in countries with poor infrastructure.

There is no guarantee all of this will happen. It could still crash and burn, especially if more serious security and privacy problems emerge.

But based on what I’ve seen in the last few weeks, Zoom is on a better path than that. I’m optimistic. Are you?

In a word, yes.

As you point out, Zoom is the anti-Facebook. The latter’s customers are advertisers and users are a means to an end. Zoom is very different in this regard and, perhaps more important, there’s plenty of competition in the area. Researching Zoom For Dummies, I was amazed to discover how many companies are out there capable of providing similar service.

I saw Alex Stamos post that he is consulting with them. In my opinion that’s a pretty big feather in their cap to have that help.

“Zoom got ahead by making things easier for users and breaking rules its competitors abided by”

Were they naive, or were they malicious?

Assuming it’s the former, is it okay in 2020 for a tech company to be naive about security? It’s a great product, and a great UI, but I’m not convinced yet. Only time will tell.

Josh,

Let’s consider two of the more serious issues:

1. Zoom said falsely that it used end-to-end encryption.

2. Even after you uninstalled the program, it remained on your computer.

It seems disingenuous to suggest that Zoom made these decisions to benefit the customer.

I’m glad Zoom is making changes — and it’s impressive they’re doing so with such speed under such trying circumstances. Also, Zoom is a great product.

But I think it behooves us to balance our praise with an acknowledgment that they screwed up.

Zoom is powerful,.easy to use, and dead wrong on their encryption policy. I realize that many corporations won’t care, but others will. https://www.theverge.com/2020/6/3/21279355/zoom-end-encryption-calls-fbi-police-free-users