How you can achieve Ikigai, fulfillment

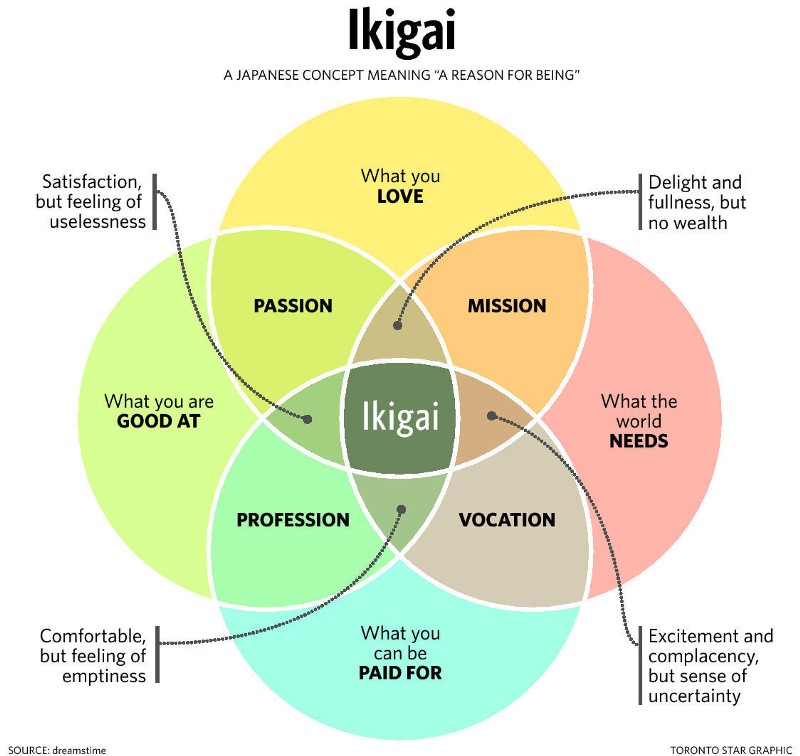

There’s a graphic making the rounds; I first saw it posted by Jeremiah Owyang. It’s about the “Japanese concept” of Ikigai, or “a reason for being.”

This graphic attracts us because the circles — what you’re good at, what you love, what the world needs, and what you can make money at — are certainly part of what many of us are striving for.

I am here to announce that I have achieved Ikigai.

This is nothing special. In fact, you can achieve it easily as well. All you have to do is lower your standards. If you imagine that you are good at something, you enjoy it, the world needs it, and you have enough money, then congratulations, you too have achieved Ikigai. All you need to do is delude yourself and you’ll clear the bar in all four areas.

Obviously, this method of achievement leaves a little to be desired. This concept is obviously about striving, not settling. But there is some truth to the idea — specifically, that happiness lies in the convergence of your abilities and your dreams, and you will have to adjust both to be happy.

So let’s dive into this question a little more carefully, in search of strategies that might help you get closer to the center of the diagram.

Start by considering your privilege

While you are striving for Ikigai, some person you are passing on the street, or have never heard of in Bangladesh, is attempting to scratch out a living. She may not have enough to get the medications that would allow her to strive for anything. He may live in a place where getting enough food or water is a full day’s work. These people are not thinking about Ikigai, they are thinking of survival. If you are an educated person in a rich and safe part of the world, you are already starting way ahead. So I recommend that we start by being thankful that striving for fulfillment is even an option.

The other thing that is not on this diagram is the concept of unavoidable setbacks. If your mother died when you were two and your stepfather abused you, you may find this diagram to be taunting you as you face your own emotional difficulties. If you have medical problems, must care for an autistic child, suffer from addictions, or are being stalked by racist trolls, perhaps Ikigai is not at the top of your list of priorities — fixing your problems is. Admittedly, such a fix would help get you on the path, but I want to acknowledge that considering fulfillment is a luxury.

I was born into an educated life; my father was a college professor, and I was gifted with mathematical ability. My family and I have our share of medical and other challenges, but at least we have a stable family that can support each other. So I have the luxury of contemplating this diagram.

One other thing. While I will not go into my family’s personal issues, there are many who, if they heard my story, would feel we were in need of sympathy, or even pity. I prefer to see myself as lucky to have the resources to face these challenges, which look more to me like the work of being human. Whatever you’re facing, if you can find a way to get to a place like this, it will certainly help.

Improving in four dimensions

If you’re not in the center of the diagram, you have some work to do. How can you do it?

Getting paid

When you are young, finding a job that pays is a challenge. Many young people with degrees are now working as retail salespeople or other jobs that don’t necessarily lead to a fulfilled career path. But eventually, most of us find a way to get onto that bottom rung of the ladder.

There is a strong social pressure to continue to advance by chasing promotions, switching jobs, and squashing rivals. Unless the pursuit of money is your primary motivation, this path is unlikely to leave you happy. (If the pursuit of money is your primary motivation, you’re either very shallow, deep in debt, or headed for a midlife crisis.)

A smarter path is to identify which of your talents and abilities are most valued by employers, and invest in those. That might be coding, managing, organizing, coaching, or any of a hundred other skills. If you can get noticed for those talents, people will hire and pay you more, you’ll get better, and you’ll ascend.

But what if the work you like doesn’t pay much? What if you’re a teacher or welfare case worker or firefighter and that’s what you love?

To increase your overall compensation, you might:

- Find an area to specialize in, where talents are rarer and pay is higher.

- Marry someone highly paid, so there is less pressure on you to be the primary earner.

- Move to a place where prices are lower.

- Make living frugally part of your ambition.

- Develop a higher-paying sidelight — what do you do that’s not a career, but people will pay for?

- Ask for stock options.

Getting good at things

College is not training for a career. College is training for getting started in a career. It’s rare that people begin in the workplace as experts.

To get good, you need experience. But more than that, you need to pay attention. You cannot learn until you recognize that you need to learn — and that there are others from whom you can learn.

Part of this task of development is to recognize that you may not yet know what you are going to be good at. There are areas in which you are not yet skilled (Public speaking? Project management? Design?) that might be places where your talent can develop.

To get better at work skills, you might:

- Find something you think you’re good at, and do as much of it, as often, as possible.

- Identify a mentor who is better than you, and tap her expertise as you learn.

- Identify the next level of mastery; set that as a goal.

- Find role models — when you think of success, who do you want to be like?

- Find learning resources, such as seminars, events, and advanced training certifications.

- Try new things you don’t know about to see if you might be good at them.

- When you fail, concentrate on what you would need to change to be better.

Loving what you do

People tend to love what they are good at. Skill creates pleasure.

Still, I know many people who have jobs where they can do things easily, and are bored.

Part of developing this enjoyment is a question of attitude. The guy who cleans my house is one of the happiest guys I know. He has found a way to take joy in house cleaning. Is there any joy in the things you are doing? How closely have you looked for it?

To enjoy what you do more, you might:

- Identify which parts of your work make you happiest, and focus more on those.

- Determine if there are toxic elements of your work that interfere with your enjoyment (a bad boss, for example, or a poisonous company culture) and make a change to get away from those antagonists

- Look for people who are happier than you doing similar work, and ask them where that happiness comes from

- Concentrate on developing happiness in your home and family life, to improve your attitude

- Try some completely different things, both at work and outside of it, to see if they make you happy

Doing work that matters

When I was young, I met a man who had a business doing options valuation. He identified my mathematical talent and attempted to hire me. I could clearly do the work, but in the end, I was uninterested in doing it, because securities valuation seemed meaningless to me. I was much more interested in doing work that helped people (then, technical writing; now, blogging and writing books).

It is a terrible mistake to spend your time doing work that lacks meaning. You will find it hard to get to the end of the day, no matter how talented you are or how much you get paid. Such work is a dead end.

To add meaning to the work you do, you might:

- Think harder about the meaning in what you do. All jobs are meaningful, but sometimes you need a bit of research to identify how.

- Shift into a sector where the work is more meaningful, such as nonprofit work or services.

- Figure out who your are jealous of based on the work they do — is it trainers, or writers, or coders, or managers? Then seek assignments that allow you to sample those roles.

- Find meaning outside of work, through volunteering, community service, friends, or family.

The journey matters more than the destination

I’ve been working for 36 years now. Getting to a state where I am well paid, skilled, happy, and creating meaning took a long time. It is a path worth pursuing, with many twists and turns along the road.

I have enjoyed following this road, and I do not feel like I’m near the end of it.

Everything I do has led to something better. That includes getting divorced, being laid off, creating a book production department that wasn’t in the job description, firing people who I’d made mistakes in hiring, and working with a few idiots along the way. I learned from all of it. I could not have gotten to this relatively happy place without those experiences.

I think the greatest skill I have learned is a skill that nobody puts on the Ikigai chart: the skill of enjoying challenges. Building a business was a challenge. So was writing research reports. So was finding ways to get paid for giving advice. So was standing up in front of a crowd and speaking. So was writing stuff that wasn’t bullshit. So was raising a family. I have learned that throwing myself into these challenges pays off.

They were hard, and I failed a lot.

It was worth it. And it continues to be worth it.

If I stop taking on challenges, check my pulse, because I’m probably dead.

I wish you success on your own voyage to Ikigai.

Protractor City. Color Wheels. Infographics gone wild. 9 miles of bad road.

12 layers of pain. 5 aces mean trouble. Bullshit.

Old Zen saying: Can’t see the moon? Burn down the barn.