How to plan and write a useful memoir

Have you had an interesting life? Could others benefit from your experiences? Then you might write a memoir. But how should you structure it? Let’s look at two ways to structure a memoir filled with valuable lessons.

I’m working with several authors on memoirs right now, and I developed these approaches to help them. One has been a senior executive in some of the most consequential startup companies in the last 20 years; the other had a distinguished military career that led to a fascinating entrepreneurial journey in the private sector. Both share a common problem: how to structure the narrative?

The obvious answer is “chronologically.” And for the startup executive, that’s exactly the right answer, because one experience leads into another. But for the military leader, a chronological approach wouldn’t be the best approach to communicate the lessons they’ve learned over their career.

To analyze structure, create a memoir idea chart

If you believe your life has lessons to teach, take this opportunity to list out those lessons. Let’s call them “principles,” since they reflect basic truths that you hope the reader will take away. For example, your list of principles might look something like this:

- Courage under pressure. Don’t wilt when the going gets tough.

- Deciding is better than equivocating. Any decision is better than no decision.

- Balance life and work. Don’t get so swallowed up with work that you lose what matter most.

- Bad news first. Don’t just hope, address problems.

- Eliminate toxic team members. Assholes destroy everything.

These are obvious platitudes, but in a memoir, you could make them meaningful with stories. I made them up — yours will be different. (I hope — if these are your principles, feel free to use them.)

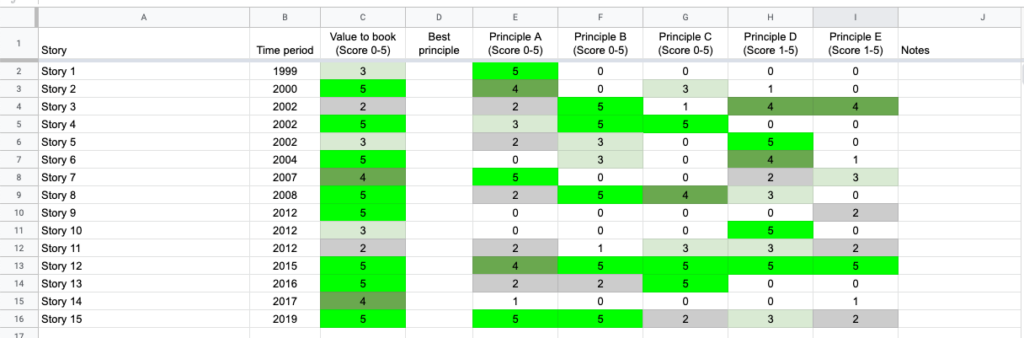

Now make a chart like the one below that lists the stories in your life, one per row. Include the date. Score each story from 0 (worthless) to 5 (fascinating) on the value to the book (basically, how interesting is it and how instructive is it). Also include a 0 to 5 score rating each story on each principle. You’ll create a spreadsheet that looks something like this, except your principles and stories will have actual names (like “getting fired from first job). In the version shown here, I’ve color coded the scores with conditional formatting; that’s optional.

You’ll notice some patterns immediately. First off, you’d better have a lot of 4’s and 5’s in the Value column. But look down the other columns. Some have a of good stories for them. Others have fewer stories to illustrate them.

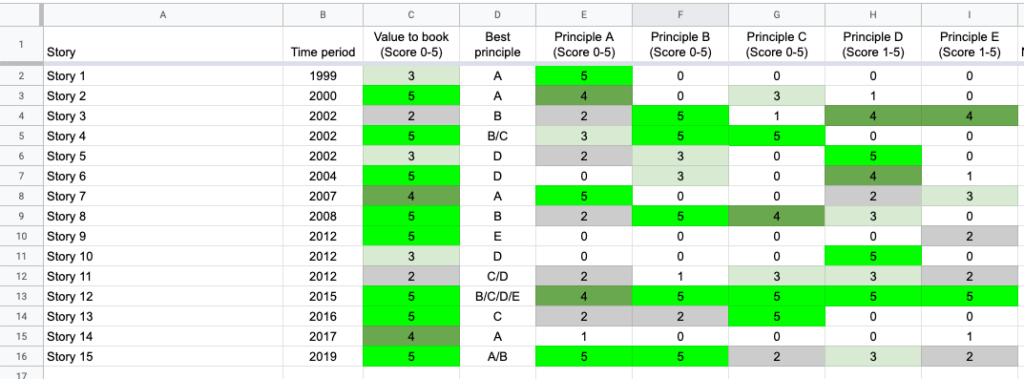

Ideally, you’d like to have a chapter for each principle. But do you have enough stories to do that? Add a notation about the best principle for each story in the “Best principle” column. Now you’ll have something that looks like this:

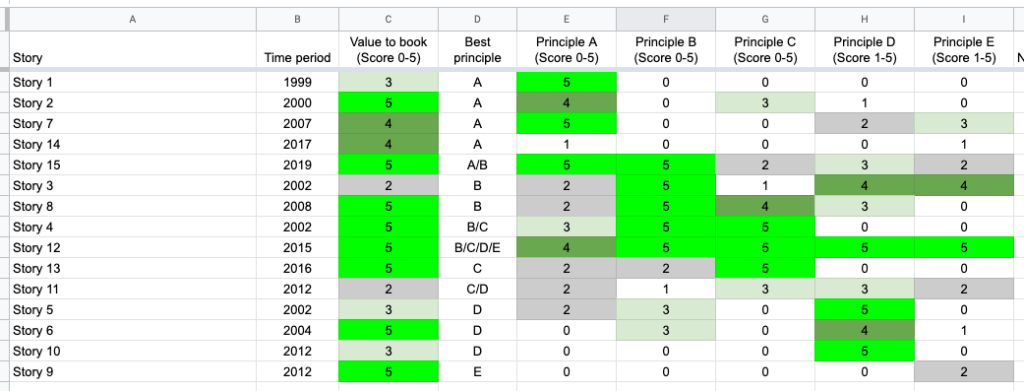

Now sort based on the “Best principle” column. (If you make sure to keep one story per row, you’ll be able to do sorts like this, which is crucial to this method.

The stories are no longer in order; now they’re organized by the principles they illustrate. And some things are immediately clear.

You have many stories for principles A, C, and D, but you are very thin on principle E. The stories for principle B are shared with other principles — which chapter do they belong in?

Assuming you tell each story only once (which is best to avoid repetition), you can now reclassify stories based on where they are needed most and sort again. For example, Story 12 had better go under principle E because even though it illustrates so many principles, The chapter on Principle E is the one that needs it most.

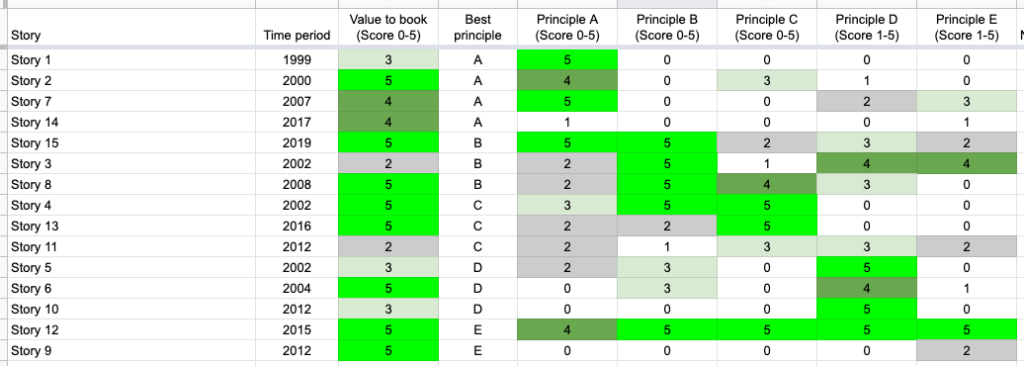

Now the sheet looks like this, after resorting.

Now you know the health of your manuscript.

- The chapter on Principle A has three good stories. You could easily dump Story 14, which appears to be pretty weak.

- The chapter on Principle B is fine with three good stories.

- The chapter on Principle C has two good stories and one weaker one. Consider whether you need another story or a way to make Story 11 stronger.

- The Chapter on Principle D has three strong stories.

- The Chapter on Principle E has only one good story, and one weak one. Consider what other stories you can think of that would help here, or reconsider you definition of Principle E.

This analysis tells you what stories to keep, which ones to dump, where you need more, what order they belong on, and might even suggest ways to rethink the principles.

Even if you decide to write your memoir chronologically, a tool like this can help you draw out the themes you’ll emphasizes and the chapters in which you’ll refer to them.

You can also use a chart like this to take non-memoir material, such as research information that backs up your principles, and organize that research in ways that best fit your memoir.

Of course, a chart like this is only a starting point. But it’s like an x-ray of your manuscript before it’s even assembled. And that’s a useful diagnostic tool to use before you start laying down text about your recollections and wondering what it really means.