How to do “comps” in a book proposal

Every book proposal includes “comps” — competing books. You need to show the potential publisher that you know what other books are out there and how you can differentiate your book from other similar books.

Why you need comps

There are three reasons to include comps in your proposal.

- Show you know your market and demonstrate your knowledge of what other books are available.

- Show that similar books are selling well.

- Show that your book is differentiated from other books in its market.

Publishers you pitch will already know some things about your general market (say, leadership books or books about being a new parent). In part, they read your list of comps to see if you see the market in the way they already do, or differently. But they will also use your list to educate themselves about the details of your specific market (say, leadership for millennials) that they didn’t previously know.

Finding comps

You need to compile a list of about six to 15 books that are similar to your own. (Strangely, nobody in publishing wants to take a chance on a book that’s completely different from everything else, so there are always some sort of comps.)

What does “similar” mean?

- Similar topic. If you wrote a book on content marketing, what other content marketing books are there?

- Similar audience. If you’re targeting Gen Z job seekers, what other books are there for Gen Z’s hoping to make a professional impression?

- Similar appeal. If you’re writing a memoir of your life as a woman in startups, what other books are memoirs of women in challenging professional settings?

- Similar format. This applies only if your format is unusual. If your book is a book of cartoons about corporate politics, what other similar cartoon books are there? If you have a book of data visualizations in color with elements identified and called out, what other books feature color illustrations with callouts?

How do you find the comps? Start with the ones everybody knows. For example, Ann Handley and C.C. Chapman’s Content Rules was a popular and influential content marketing book. It’s crucial that you know these iconic books in your field, because leaving them out would demonstrate that you’re out of touch with your own topic.

Do some searches on Amazon for key terms. But also do searches on Google. For example, if you’re writing a book about women in the military, here’s a blog post listing must-read books about women soldiers.

It also helps to ask your friends. Post on Twitter, Facebook, and Linked In and ask “What are the most important and successful books that you know on topic X?” You can also ask individuals who you think are knowledgeable about the field.

If a book in your field made a particular impression on you, include it as well.

Culling the list

You may find 30 potential comps. But you don’t need to list them all. Some books aren’t really relevant.

To help cull the list, you’ll want to examine the Amazon and Google Books listings of the books you’re potentially positioning against.

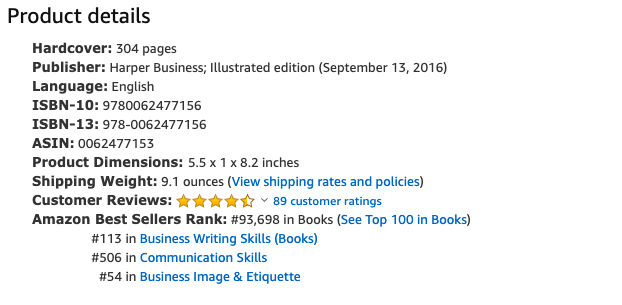

Pay close attention to two qualities of each book: the number of Amazon reviews and the publication date. You can find the number of reviews, publisher, and pub date by scrolling down to the Product Details section of the Amazon listing. Here’s what that section looks like for Writing Without Bullshit, for example:

Which books should you eliminate? Cull books that are:

- Old. Books first published more than 20 years ago don’t belong on the list, unless they are perennial sellers (like, say, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People).

- Unpopular. If a book has fewer than 15 reviews, it probably made very little impact. Including it in your list of comps won’t show much. Exception: if the book is extremely similar to your book, you’ll need to explain why your book will succeed where this one failed.

- Self-published. If the publisher is “Amazon Createspace,” “Kindle Direct Publishing,” or “Ingram Spark,” the book is self-published. If you don’t recognize the publisher name, Google it — if it’s a traditional or hybrid publisher, you’ll find an extensive publisher site; otherwise, it may just be a publisher name made up by the self-published author. Self-published books with more than 40 reviews are still worth including, but you can ignore the rest.

These indicators tend to go together — self-published books often have few reviews, as do books that are so old they were published before Amazon came into existence in 1994.

What you are left with should be the credible books that are most popular or most similar to your own.

Now you need to add commentary

For each book on your list, you need a little story. Your story should imply that you’ve read or at least investigated the book and have an understanding of how it stacks up to yours.

Start your story about the book with a short summary of how it impressed you. Include indicators of sales, such as whether it made the New York Times bestseller list (if it did, the Amazon description will certainly mention it) and how many reviews it has. Here’s a rule of thumb: a book with more than 300 reviews was popular and one with more than 1,000 reviews was extremely popular.

Then you’ll need to explain how you position against the book. This bit is in one of three basic categories.

- This book sold extremely well, and my book is another example of the same sort of book, so my book will also sell well.

- This book was somewhat popular — my book is different and better, and here’s how.

- This book was not that successful, because of [reason]; my book will do well because it is much better.

For example, here are some of the comp descriptions from the original proposal for Writing Without Bullshit. Notice that when a book is good, I say so: there’s no point in disparaging other excellent books.

The Elements of Style (by Strunk and White, 4th edition, Longman, 1999): A fantastic book for a general audience. Great tips, but it was originally written before there were computers, smart phones, or word processors. I genuflect in Strunk and White’s direction, but we now need a guide for writing in a very different environment.

On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction (by William Zinsser, 30th anniversary edition, Harper Perennial, 2006). Originally written for a general audience, rather than business writers. Updated in 2006, but it does not acknowledge how computers and the Internet have changed the way we consume writing.

The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century (Steven Pinker, Viking, 2014). Pinker is a genius, and this is a nicely done manual on writing. But like most writing books, this is a general style manual, not one designed for businesspeople. Pinker himself says his book is for those writing in the “classic style” of narrative, rather than what he calls “practical style,” or writing that gets stuff done.

The Dictionary of Corporate Bullshit (2006), The Dictionary of Bullshit (2006). Novelty items; these are not writing manuals.

Why Businesspeople Speak Like Idiots: A Bullfighter’s Guide (Brian Fugere, Chelsea Hardaway, and John Warshawksy, Free Press, 2005). A devastating takedown of corporate blather and why it happens. Very strong on motivation, but it’s not really a writing manual or how-to book.

Everybody Writes: Your Go-To Guide to Creating Ridiculously Good Content (Ann Handley, Wiley, 2014). This is an excellent book and workaday manual for writing in the Internet and smartphone era, covering everything from email to blog posts. It’s written in very short chapters with a highly practical bent. Writing Without Bullshit is more ambitious — I go into a lot more detail about motivation and what it is that makes writing for on-screen reading most effective. Basically, while Ann’s book tells you how to write, I tell you how to stand out in your career by writing well.

You don’t have to read the books

If you’ve read the book, the comp descriptions are easier to write.

But if you haven’t, you can still write them with other material you can peruse quickly. This includes:

- The description on the Amazon site.

- What you can see in the “Look inside the book” on the Amazon site, which usually includes the table of contents and the introduction.

- Reviews of the book online.

- Your impressions after buying the ebook and skimming it. (Once you buy an ebook, you can instantly read or skim it at read.amazon.com).

- Your impressions from skimming the book at a bookstore. (I suppose some people do this; it seems pretty inefficient to me.)

Reviewing competing books is good for you

While you have to do comps for your proposal, it’s actually a worthwhile activity in its own right.

If you discover a successful book just like yours, that’s your cue to either give up or find a new way to differentiate.

If other books are similar to yours but not the same, this helps direct you towards creating unique elements so your book can stand out.

We are all in a community of authors. Reviewing comps will help you figure out where you belong in that community.

This is extremely helpful. My only question is, when you include a book in your comps that is similar but it is one of three in a series (and yours is not), do you give all the details for each one, or just mention that it wasn’t a stand-alone book? Obviously the newest one should be the main one mentioned. I think in the instance I’m referencing, though, the first one may be more similar to mine than the other two. Maybe it just feels that way.