How to cite research that isn’t crappy

If you’re writing, you’ll want to cite published research that you didn’t do yourself. Here’s how to find research worth citing — and avoid citing crap research.

Think of me as your mom, saying “Don’t put that research in your document. Do you have any idea where’s it been?”

Finding research to cite

How do you find points to cite? If you made notes about or recalled something you read earlier, go back to it. But if not, you’ll start like everyone else: with Google.

Let’s look at an illustrative example. How are companies now dealing with remote working policies?

Perhaps you type this into Google: “remote work survey covid”

Here are the top results I see (your results may vary, depending on your search history):

So let’s see what’s worth citing. When you’re reviewing any survey research, ask these questions:

- Who did the research? Is this a source I can trust? Is there a bias?

- How recent is it?

- How many people did they survey? What kinds of people?

- What is their sampling method? Is it representative?

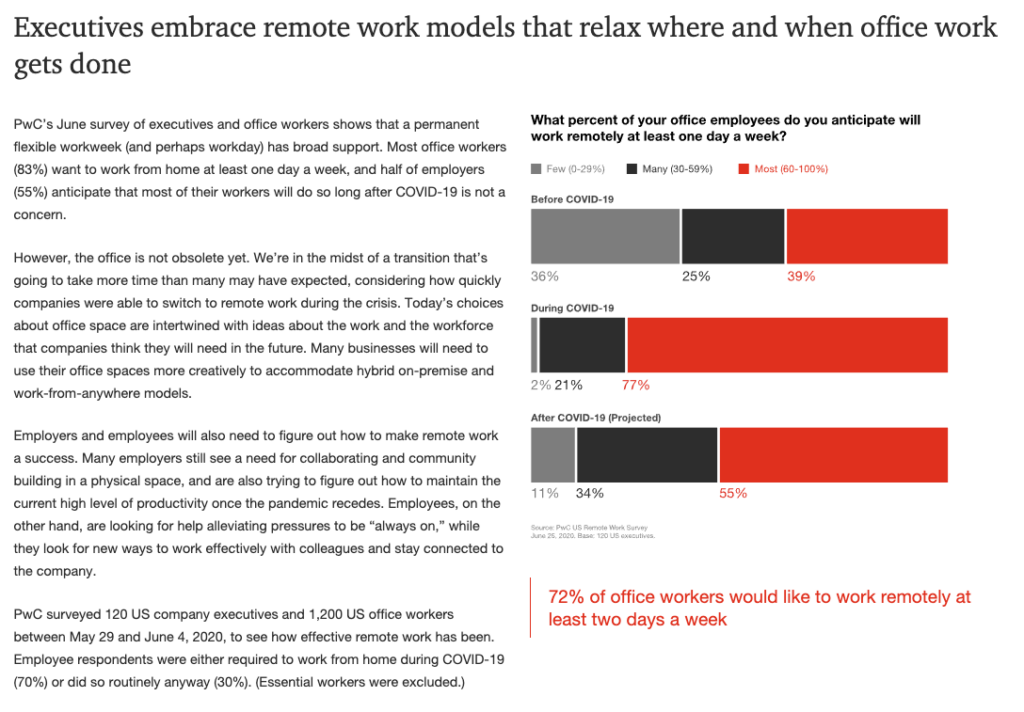

Let’s start with the PwC link. It looks promising. Here’s a sample:

Can we trust it? Well, first off, PwC is a large global consultancy, so I’d expect quality research without significant biases. The survey was done in early June, 2020; things may have changed since then, but it’s far better than a survey from January or March. It reached 120 executives and 1,200 office workers. I’d be skeptical of results from only 120 executives, including the ones shown in the bar chart, but the larger sample of workers is likely to have valuable insights.

There’s more about the sample. At the bottom of the page is information about the survey methodology:

PwC surveyed 120 US executives between May 29 and June 4, 2020. All respondents were from public and private companies in three sectors: financial services (42%), technology, media and telecommunications (29%), and retail and consumer products (29%). Eighty-three percent of respondents are from companies with annual revenues greater than $US 1 billion. Of the participants, 40% have Chairman, CEO or Executive Director titles, and 18% have Vice President titles.

To understand employee needs, PwC surveyed 1,200 US office workers from a range of industries between June 1 and June 4, 2020. They all identified themselves as employed and currently working remotely — either because they were required to work remotely due to shelter-in-place mandates (70%) or were already working in a flexible arrangement with their employer (30%).

Now we see a few more biases. the executives are in only three industries, and are skewed towards companies with $1 billion in revenues. So you’d be making a mistake by citing this to represent decision-makers in all companies, including companies with revenues below $1 billion.

You could cite a statistic from this survey like this:

In a June 2020 survey of 120 executives, mostly from large finance, technology, media, telecom, retail and consumer products, PwC found that 55% anticipate that most of their employees will work remotely at least one day a week.

What about some of the other sources? The WorkTango link isn’t a survey, it’s suggested questions for your own survey.

The Slack link leads to a March survey of 2,877 knowledge workers — so you have to be careful with it since conditions have changed since March. And when Slack states that “Remote workers who use Slack are more likely than non-Slack users to report that their productivity actually improved when working from home. They’re also less likely to experience feelings of loneliness, isolation and disconnection while working remotely,” you need to acknowledge that the source is biased. (What did Slack find that was negative, so they didn’t publish it?) There is nothing deceptive here, nor am I suggesting that Slack skewed the data, but the source matters for statistics like this.

Some sources require you to dig deeper. Others you should avoid.

News articles often cite statistics. For example, consider an article from yesterday in CNN, “The shift toward remote work could leave blue-collar workers behind.” The author has thoughtfully done research for you. Consider this passage:

According to a June 2020 report, 42% of the US labor force — about 70 million people — were working from home, while 26% were continuing to work on-site. (The remaining 33% were not working.)

You could quote this directly. But that would be lazy. Where did that 42% number come from? Click on the link and you find a June 29 interview with Stanford Economist Nicholas Bloom, who says “We see an incredible 42 percent of the U.S. labor force now working from home full-time.” But how does he know? A link within the interview leads to a study from the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR). The number is from a May 2020 survey of 2,500 US residents aged 20-64, earning at least $20,000 per year. That’s what you should cite, not the CNN article. Note that it took two clicks and a fair amount of reading to get to this result. Research is work — you have to go a little deeper to get it right.

There are two sources you should avoid citing altogether.

One are random blogs you might find, which includes articles in Medium or Huffington Post. And when citing sources from Forbes, use caution. Forbes has sullied its brand with thousands of “Forbes Contributors” who have no particular qualifications. For example, you might be tempted to cite this article: “Will The Remote Work Boom See A Rise In Digital Nomadism?,” by Forbes Contributor Adi Gaskell.

But who the heck is Adi Gaskell? According to the blurb at the bottom of the article, Gaskell is “a free range human who believes that the future already exists, if we know where to look. From the bustling Knowledge Quarter in London, it is my mission in life to hunt down those things and bring them to a wider audience. I am an innovation consultant, writer, futurist for Katerva, and the author of The 8 Step Guide To Building a Social Workplace.” In other words, a random “thought leader” with an opinion.

The second source you should avoid citing is Wikipedia, since anyone can edit it to say anything.

This is not to say that Forbes contributors or Wikipedia are useless as sources. They often contain links to more definitive sources. But track down the extra links and cite them, not the Forbes contributor or Wikipedia.

Sloppy research creates a terrible impression

Any time I see a number or quote in print, I wonder where it came from.

If it is the result of primary research that the author conducted, I’m impressed.

If it’s from a reputable source, properly cited, I find it credible.

If there is no source cited, or the source is questionable, the author’s credibility goes way down. You may think you’re shoring up your argument with such facts and quotes, but you could be creating quite the opposite impression.

So take the time to do research properly and you won’t undermine the rest of what you’re writing.

Please don’t forget librarians and libraries. Many businesses and institutions have both and can provide excellent sources that may or may not be found in Google. In fact, in these days of pandemic and social distancing, many research services provided by librarians are accessible virtually. And don’t overlook your local public library – many have excellent database collections and highly knowledgeable librarians.

I love your blog. Thank you.

I would repeatedly tell my students to consider the source. Anyone can find “proof” of anything on the Interweb. I tend to take software vendors’ claims with a 50-lb. bag of salt.

Thank you Josh. This post is so good I am sharing it with 150 participants in my white paper writing course. Naturally, I’m urging them to do deep research. You give excellent examples of how to do this.