How the empathetic expert generates trust

I was thinking about why I trust one particular doctor more than others. It comes down to two things: expertise and empathy. Neither, by itself, is sufficient.

The doctor is Caroline Levine. She is a specialist who I visit at least twice a year, and who is protecting my health from serious jeopardy. She has also done several minor surgeries on me with caring and precision.

My experience with Dr. Levine is probably similar to yours with the medical professionals you count on — complicated. She must explain complex concepts in an environment where there is more than a little fear. She’s dressed professionally; I’m sitting there vulnerable with lots of skin hanging out. She has to do painful things to me that are necessary for my health. And I am, by nature, a skeptic (as any regular reader of this space is aware).

All of these factors have complicated our relationship. And yet, I feel a solid trust with this professional and am highly likely to follow her advice in any area related to her expertise.

Why? Where does trust come from?

Why expertise and empathy are both necessary

I’m a believer in facts and logic. I like to believe that I think for myself. I am well-read and thoughtful on a variety of topics.

This means that if you don’t know what you’re doing and lack experience — or if it appears that way — then I am not going to fully trust you.

(When my primary physician was unavailable for a regular appointment recently, the office recommended a substitute. “He’s new here, but he has been practicing for a while,” the office person told me on the phone. My response: “Practicing is fine, but I sure hope he’s gotten the hang of it by now.”)

That’s expertise: the experience and wisdom to recommend the right course of action, and to logically justify it based on verifiable facts and knowledge.

What about empathy? I don’t just want an expert. I want an expert who understands what’s best for me. That means they need to care about me as a person and understand what I’m going through. If they can communicate that, it goes a long way. “I know this will be painful, it will be over soon.”

The empathetic expert knows, not just what to do, but how you feel. They know you may be anxious or uncertain. They know you are part of a family who may also be affected by your decisions. They know you are in a vulnerable position when you ask for their help. And their response comes from a human place — they can understand how you feel, and take that into account when they response.

Both expertise and empathy are necessary here.

If you have empathy but no expertise, you generate resentment. “There, there, you’ll be fine, that must be awful for you.” When I hear that, my back goes up. I have no interest in your uninformed, generalized caring. I’m here to get help, not love. Professionals like this often wonder, “Why do people respond negatively to me?” It’s because instant, uninformed empathy is false. It doesn’t generate trust.

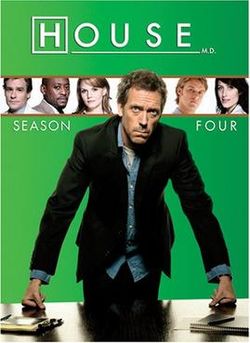

On the other hand, if you have expertise but no empathy, you are also hard to trust. I think about House, MD, in the medical series “House.” He always knows the right thing to do, but sees patients only as problems to be solved, not human beings. I have known doctors like this, who are always delivering bad news soullessly as if the naked truth is all that matters. It’s very hard to take advice from people like this, because your own emotional situation is part of the equation, and they are ignoring it. I prefer to take advice from people I like, and people with no empathy are hard to like.

If you give advice for a living, this should matter to you

A lot of us now make our living by consulting — giving advice to people. I do this as an editor and in writing workshops. I am telling people what to do.

My expertise allows me to be credible. When I tell you how to write better, it’s based on seeing dozens of books in progress and, literally, millions of business communications. I know what works and what doesn’t. I’ve been thinking about it for many, many years and have tested and refined my ideas in practice.

My empathy is important, too. I have attempted to rally people to a cause with email and I know how that feels. I know how hard it is to write a book chapter. I am not just dictating what is right and wrong from on high — I am explaining based on what I perceive as your context. I’ve been there.

This has been a winning combination. People accept — and rarely resist — my advice, because they know it coming from a position of expertise and empathy. You can trust me. And as a result, you will likely come back, expand the relationship, and refer others to me.

Anyone who gives advice is going to have to deal with this. You are going to tell people they’re wrong, they need to do things differently, they need to scrap work they did and start over in a new direction. This is hard. Without empathy, they’ll perceive you as condescending and hostile. Without expertise, they’ll perceive you as arbitrary and untrustworthy.

Empathetic expertise. It’s a winning combination. It’s hard to build up, but it’s essential to your success as a consultant.

Love this. It’s the perfect example of Aristotelian ethics at work. Artistotle outlined logos, pathos and ethos as the fundamentals of persuasion. Logos is your expertise, or how you marshal facts and logic; pathos is how you establish empathy and related to others; ethos is your integrity or the trust established as a result.

Your experience with your doctor effectively illustrates all three.

Love this!

And it relates (somewhat) to the current Covid mess, especially the widespread resistance to the vaccines.

The authorities charged with informing and advising the public (Fauci, etc.) are high in expertise; they have decades of experience (research and practical applications) dealing with infectious disease, immunology, vaccine technology, etc.

However, they fall short in empathy. They’re often ineffective communicators, because they don’t understand how *emotional* reactions affect how people interpret and act on information. When people are already emotionally aroused (here by longstanding fear), they’re primed to react emotionally to anything that triggers the fear; they’ll hear a message *emotionally*, and thus bypass the facts/logic. In persuading people to do what seems best from a public health standpoint, these experts should phrase their comments strategically. “How” it is said is as important as “what” is said.