How long does it take to write a book? A detailed analysis of author hours.

“I want to write a book,” you say. “That’s a huge undertaking,” your author friend responds. But how big is “huge?” Here’s a detailed way to think about the time it will take.

How to use this planning tool

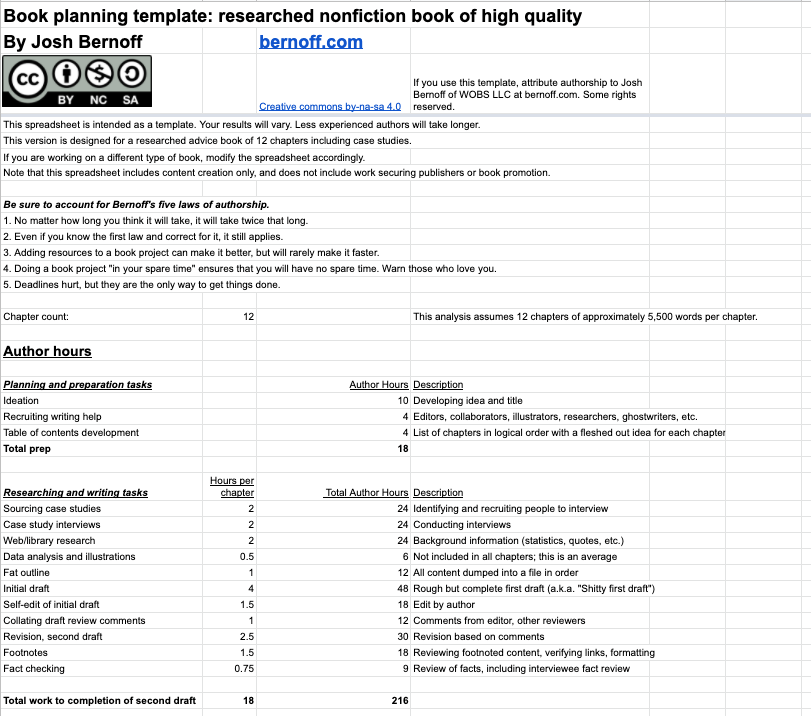

To make your planning more effective, I have created a publicly available spreadsheet showing book tasks and the time it takes to complete them. You’re welcome to review this. If you want to use it for your own purposes, make a copy and work from that. (Feel free to modify or republish the spreadsheet, but any public use requires attribution to me at bernoff.com and with the same sharing rules.)

This spreadsheet addresses the types of books I work on most frequently: researched nonfiction advice books of high quality. If you are working on a different kind of nonfiction book, you’ll want to modify this spreadsheet to account for the tasks associated with your type of book, but the template should still be helpful to you. (If you write fiction, I have no idea the tasks associated with that, so I can’t help you.)

I cannot emphasize enough that your mileage may vary. Some books require far less research and may not include cases studies. Some authors write very quickly or very slowly. Some authors are willing to publish first drafts and don’t worry about quality (and if you are one of them, please get off my blog).

If you are creating a book of high quality, this analysis applies regardless of your publishing model — traditional, hybrid, or self-publishing. However, this analysis does not account for the time spent to create a book proposal for traditional publishing. It also accounts only for research, planning, writing, and revision, and does not include any of the additional effort you will need to spend on promotion.

Finally, to make your planning more realistic, here are Bernoff’s five laws of authorship:

- No matter how long you think it will take, it will take twice that long. There’s always something you don’t anticipate, and most people overestimate their own productivity. This is especially true for first-time authors.

- Even if you know the first law and correct for it, it still takes twice as long as you think.

- Adding resources to a book project can make it better, but will rarely make it faster. You can add a ghostwriter, but then you have to supervise their work. You can add an editor, but then you have to address their comments. You can add a researcher, but then you have to determine what part of what they find is worth including. These sorts of efforts may reduce the number of hours you need to spend on the book, but won’t make it go much faster.

- Doing a book project “in your spare time” ensures that you will have no spare time. Warn those who love you. If you’re lucky, you can budget time away from your other projects. If you don’t do this, progress will be difficult and painful.

- Deadlines hurt, but they are the only way to get things done.

The planning and preparation stage

The first thing to do when writing a book is not to write. It is to plan.

Planning includes title and idea development, which is a task you undertake, usually with the help of others, do define the main idea in your book. It also includes sourcing and hiring freelancers (or people within your organization) to help as developmental editors, collaborators, illustrators, researchers, or ghostwriters. Finally, you should put at least four hours into developing a detailed table of contents as a roadmap for the writing process.

For a quality, researched nonfiction book, the total time spent on these tasks is about 18 hours.

The research and writing stage

Now you can start creating. That’s not the same as starting to write.

For each chapter, you’ll need to undertake the following tasks to prepare before you start writing.

- Sourcing case studies. Identifying and contacting people to interview so you can tell their stories.

- Case study interviews. Conducting the interviews.

- Web/library research. Identifying the work of others that you can cite and include, such as studies, statistics, and quotes.

- Data analysis and illustrations. If you have data, you need to spend time analyzing it. And you’ll need to consider some conceptual illustrations.

- Fat outline. Assembling the ingredients in a rational order.

Now you can start writing and revising. That process includes these stages:

- Initial draft. Turn your fat outline into an actual prose draft.

- Self-edit of initial draft. Revise the draft on your own. Then send it out for review to your developmental editors and other reviewers who are helping you.

- Collating draft review comments. Gather feedback from your reviewers. If you have an editor, this often includes a phone call or video call to review what they found.

- Revision, second draft. Revise based on the feedback.

You’re sort of done now, but every chapter also needs some checking to be complete.

- Footnotes. Assemble and correctly identify the sources you cite.

- Fact checking. Review your original research to make sure you have everything correct.

How much time does this take? It depends on how much research you do, how fast you write, and how much revision you need to do. In my template, I estimate a total of 18 hours per 5500-word chapter, or a total of 216 hours for a 12-chapter book. If you think you can do this in less time, examine the spreadsheet and tell me where you will be going faster than I say. (And don’t forget the first and second laws.)

The manuscript completion and production stage

Once the manuscript is complete, there’s still a lot of work to do. Specifically:

- Completion of full, consistent manuscript. Inevitably, writing conventions shift between the first chapter you write and the last, because you learn things from practice. There are also often problems like duplicated content to fix and holes to fill. At the end of that work, the manuscript is complete, consistent, and ready to go to copy edit.

- Review of copy edits. When the manuscript comes back from the copy editor, the author must accept, reject, or address all of the copy editor’s comments.

- Review of first pages. When the publisher (or whoever is doing the page layout) pours the manuscript into a page layout program, the result a set of pages. The author is responsible for reviewing these pages and commenting on layout problems (like widows, orphans, and placement of graphics).

- Review of final pages. After the production/layout people have addressed the problems that the author cited, there are typically one or two more passes to get the pages perfect. The author has to review the various drafts of the pages and make sure there are no remaining problems.

- Admiring completed book. Set aside half an hour to sip a glass of wine and admire your finished book.

The total amount of work here is about 30 hours. And those are hours that authors typically don’t realize need to be included in the schedule.

What does this work look like for your book?

The total time budget in this template is 264 hours. If you do a book the way I do, you’ll need to find that time.

If you do the book differently, the template is still useful. You can copy and modify it based on your own assumptions. But the framework is still useful: determine how much time you need for planning, how much you need per chapter for writing and revising, and how much you need for manuscript completion and production.

Where will you get that time? That’s your problem. Just don’t go into a book project like this without an idea of the time you need and where you’ll get it.