Great writing about food: Combat-Ready Kitchen

Now I know who’s responsible for all the packaged, processed food in the supermarket.

Now I know who’s responsible for all the packaged, processed food in the supermarket.

It’s the Army.

I’ve just read Anastacia Marx de Salcedo’s Combat-Ready Kitchen: How the U.S. Military Shapes the Way You Eat, a new book published this week. I’ve known Anastacia a long time, but I had no idea she could write like this.

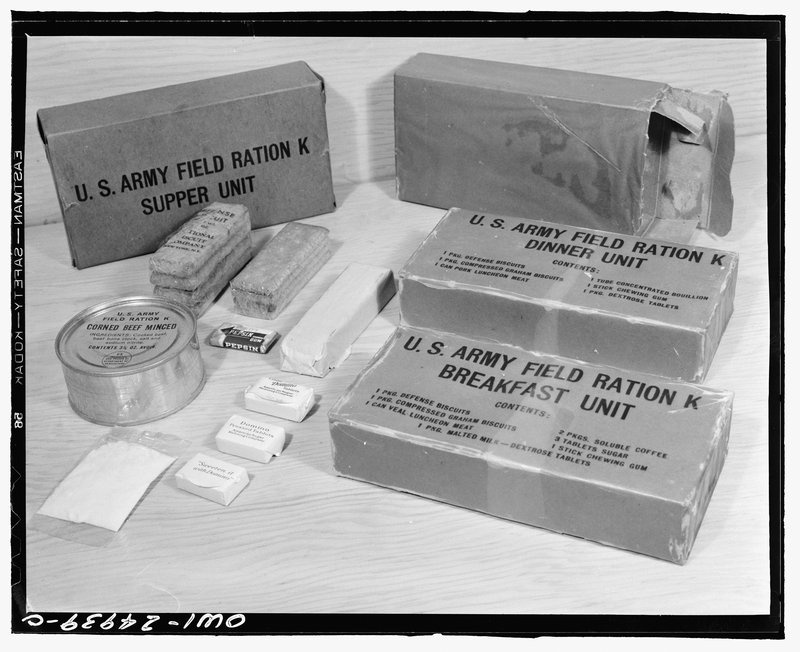

Here’s the premise: The armed forces need food. After a fascinating historical romp through feeding soldiers throughout history, we learn that there’s a massive military-nutritional complex. America’s soldiers need to eat, but food doesn’t travel well. So the nation’s food labs (and the Army’s own, in Natick, Massachusetts) gear up to find ways to prepare and package food that can get to the soldiers in massive quantities without tasting too horrible.

Need nutrition in a compact, chewy, bar? They figure out how to make it. And then spread the technology to 100 companies making everything from Power Bars to Clif Bars to Kind Bars. And we all end up eating little rectangles and pretending that they are food and not rations.

Need bread that never goes stale? The labs find the right combination of enzymes and exotic ingredients to make bread last a long time. Commercial bakeries glom onto it and we end up chewing something with only a passing resemblance to what comes out of a local baker’s oven.

Need bread that never goes stale? The labs find the right combination of enzymes and exotic ingredients to make bread last a long time. Commercial bakeries glom onto it and we end up chewing something with only a passing resemblance to what comes out of a local baker’s oven.

Now I know where processed “cheese food” came from and why everything is wrapped in plastic. We’re all eating army rations, whether we know it or not. If it’s convenient enough for a soldier on the go, it’s certainly convenient enough for working parents making dinner for the kids or packing their lunchboxes.

The best food writers, like Michael Pollan and Eric Schlosser, create poetic prose that evokes the sensory experience of manufacturing, preparing, and eating food. So does Anastacia. Here are a few samples to get your mouth watering:

Cheese purists the world over exalt their mummified milk. Their silken Goudas and savory Emmentalers. Their fetid fetas and squeaky queso frescos. Their moldy Roqueforts and runny Camemberts. These disks of rotted dairy are the pinnacle of thousands of years of experimentation that began when a herdsman carrying a ruminant’s stomach brimming with milk found that by journey’s end, he had a bag full of curds and whey.

The American carnivore — whether hypo, meso, or hyper in her habits — can go an entire week, month, or even year without confronting the animal origins of her favorite food. . . . [T]he morning begins with bacon, once a hunk of pork belly but now an almost Art Deco assemblage of crispy, striped strips . . . Lunch . . . inevitably includes restructured protein, which quietly overtook all other forms of fauna-based products in the 1990s. Dinner is the closest she gets to the real deal — ground beef; boneless, skinless chicken breast; pork tenders.

[There’s an] important reason to lace our breakfast cereal, bread, lunch meat, chips, soups, heat-and-serve meals, and cookies with salt and sugar. Our food is geriatric, and these two common chemicals do an ace job at mummifying and bestowing false youth — bright colors, firm shapes, soft textures — to edibles way past their prime.

[D]oes this stuff — immature dough whipped up with air and inoculated with exogenous enzymes — really deserve the name bread at all?. . . [A]ll those neatly packaged loaves in the supermarket — the farmhouse white, the 100 percent whole wheat, the multigrain — which have risen only fifty minutes, are not bread. What are they? In the words of the army-funded contractors whose 1950s research on enzymes helped to create them, they are “non-staling bread-like products.”

The Combat Feeding Directorate . . . is toward the back, in an H-shaped, teal-and-aqua striped building surrounded — like that drive you crazy neighbor’s house — by slightly rusting vehicles, except in this case there’s a Humvee, a camouflage-tarped assault kitchen, a shower/laundry unit, and a ten-by-twenty-foot steel box with a containerized chapel.

A good non-fiction narrative like this does three things: it evokes imagery, it keeps you turning pages, and it entertains (disks of rotted dairy? assault kitchen!). Combat-Ready Kitchen does those things, and it also taught me a lot about food, a subject that fascinates me.

Anastacia, I’ve got one quibble. “Combat-Ready Kitchen” is not a great title. It takes the focus off both the food and the people, and it’s neither provocative, nor euphonious, nor memorable. Next time, call me and we’ll brainstorm. Here are some title/subtitle ideas you could have used. (Admit it: don’t you think “Chow”or “Why You Eat Like a Grunt” sound like the titles of bestsellers?)

Chow

How Military Rations Transformed the Food We Eat Every Day

On Its Stomach

The Military Origins of the Food You Eat

Why You Eat Like a Grunt

How the U.S. Military Shapes the Way You Eat

Engineering People Rations

How the U.S. Military Shapes the Way You Eat

Food Warriors

The Story of the Geniuses Who Feed Our Soldiers . . . and How They Have Transformed the American Diet

Food Under Fire

How Military Rations Forever Transformed Civilian Food

Rations for a Hungry Nation

The Military Origins of Everything We Eat

Armed for Dinner

How Engineered Food Became the American Way of Eating

—

Photo: Library of Congress

Love that “Food Under Fire” – works on several levels!