Fake news detection for kids? How about adults?

Quartz published an awesome analysis of how teachers are attempting to teach kids to spot fake news — and how bad we all are at it.

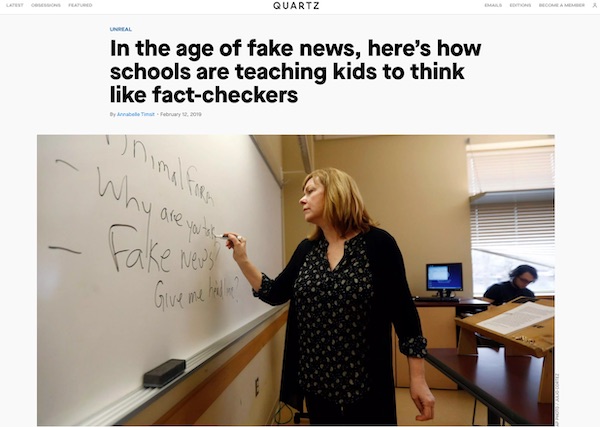

Here are some highlights from the article: “In the age of fake news, here’s how schools are teaching kids to think like fact-checkers,” by Annabelle Timsit:

About Stanford University researchers surveying young people’s ability to spot fake news:

In their own words, the researchers initially found themselves “rejecting ideas for tasks because we thought they would be too easy”—in other words, that students would find it obvious whether or not information was reliable. They could not have been more wrong. After an initial pilot round, the researchers realized that most students lacked the basic ability to recognize credible information or partisan junk online, or to tell sponsored content apart from real articles. As the team later wrote in their report, “many assume that because young people are fluent in social media they are equally savvy about what they find there. Our work shows the opposite.”

The Stanford study confirms what many teachers know to be true: Today’s students are not prepared to deal with the flood of information coming at them from their various digital devices.

Fixing it:

. . . social media and the ubiquity of digital platforms have made spreading false or biased information easier. But the core issue isn’t just technology—and neither can it be solved with better fake-news filters or algorithms. As Richard Hornik, director of overseas partnership programs at the Center for News Literacy at Stony Brook University, explains, “this is a human problem. This is us.”

In other words, people seem to be irresistibly drawn to fake news. Robinson Meyer writes in The Atlantic that “Fake news and false rumors reach more people, penetrate deeper into the social network, and spread much faster than accurate stories” because humans are drawn to those stories’ sense of novelty and the strong emotions they elicit, from fear to disgust and surprise. As the authors of a large MIT study wrote in 2018, fake news does so well online “because humans, not robots, are more likely to spread it.”

This is crucial:

The real problem is that we haven’t developed the skills to absorb, assess, and sort the unprecedented amounts of information coming from new technologies. We are letting our digital platforms, from our phones to our computers and social media, rule us. Or, as [Stanford Professor Sam] Wineburg says, “The tools right now have an upper hand.”

Current approaches to teach the problem are outdated:

As Joanna Petrone, a teacher in California, writes in The Outline:

“To the extent that teachers and librarians have been training students to spot “fake news” and evaluate websites, we have been doing so using an outdated checklist approach that does more harm than good. Checklists…provide students with long lists of items for them to check off to verify a website as credible, but many of the items on the list can be poor indicators of reliability and even mislead students into a false sense of confidence in their own abilities to spot a lie.”

. . . fact-checkers practiced “lateral reading,” meaning that they checked other available resources instead of staying only on the site at hand. That, [the authors of a Stanford study] concluded, is a practice at odds with available fake-news checklists, which focus on the outward characteristics of a website, like its “about” page or its logo, and don’t encourage students to look for outside sources. “Designating an author, throwing together a reference list, and making sure a site is free of typos doesn’t confer credibility,” they write. “When the Internet is characterized by polished web design, search engine optimization, and organizations vying to appear trustworthy, such guidelines create a false sense of security.”

And a suggested solution:

A better approach, according to experts like [Stonybrook University expert Richard] Hornik, would be to teach kids at a young age the skills of lateral learning, including how to “interrogate information instead of simply consuming it,” “verify information before sharing it,” “reject rank and popularity as a proxy for reliability,” “understand that the sender of information is often not its source,” and “acknowledge the implicit prejudices we all carry.” Anything short of that is a waste of time and resources.

Sharing is a political act

I read everything with a skeptical eye today. Every media outlet has bias; all facts are in question. The fact is, we have created an environment in which all news is easily accessible and sharable, regardless of quality. While technical fixes in the environments like Facebook are a good step, I think the resourcefulness of the propagandists at exploiting our human desire to see and share what we want to believe will always outpace technical solutions.

It’s time to recognize that reading is a political act, and sharing is voting. You wouldn’t vote for a governor or senator or president without taking a moment to research their positions. Similarly, before sharing a news item, it’s your responsibility to evaluate not just the source (Raw Story and Daily Wire are skewed and biased), but the context. What else has been written? Does this make sense in context? What makes you believe it, and what makes you skeptical? The recent video of young people visiting Senator Diane Feinstein’s office — with an edited version that delivers a story very different from the unedited version — is a perfect example of the value of context.

“I shared it because I believed it” is this century’s “I was just following orders” — it means you have abdicated your moral responsibility. If checking your news is just too much work, then don’t share it.

Each of us also has a responsibility to admit when we’ve made an error and shared something fake or doctored. I see some of this on my feeds, but have also encountered plenty of friends who are unwilling to admit they’ve been played — and even say things like “It’s the kind of thing he would do.“

News is easy. Sharing is easy. Behaving like a citizen is work. Teach your children and remind your friends — gently, but remind them.

A key line in your comments is clearly false. “You wouldn’t vote for a governor or senator or president without taking a moment to research their positions.” My impression is that vast numbers of people are in fact largely uninformed and vote based on just the kind of information that is the topic of this post.

In my post, “you” refers to my educated and thoughtful readers . . . not the general population 😉

Josh – Are we heading into a future polarisation of fake vs. trustworthy at a macro level?

Here’s the bit that caught my eye:

“I shared it because I believed it” is this century’s “I was just following orders” — it means you have abdicated your moral responsibility. If checking your news is just too much work, then don’t share it.

You might do that, and I might do that, but I don’t think the bulk of social users will do that.

Why? Because fact checking, that moral responsibility, takes time and energy. Versus the quarter of a second it takes to click Share.

The general bias for social IMHO seems to be not to converse and discuss issues with your friends; it’s to increase your own perceived self-worth by getting your ‘friends’ to ‘like’ you. I’m not talking about your readers here, but social in general.

Basically you can share crap and if it makes your friends laugh and they click Like that’s good enough.

Vs. Taking the time to check something and then add a well considered comment, intro, or follow-on to promote discussion.

While I hope I’m wrong, I just don’t see the general population rising above the “I shared it because I believed it” or “I shared it because I liked it so I think my friends will like it” mentality.

So where does that leave the future?

Does it eventually polarise new sources into a black and white fake vs. trustworthy? Facebook, Twitter, etc. bring the former. The BBC, the NY Times, the Washington Post, etc. being the latter.

And so does this give us a trust nothing vs. trust everything model?

Rather than trying to teach people to spot fake news on social, would we be better trying to teach the world to trust nothing that appears on Facebook and trust everything that appears in the NY Times?

This is not so new and not limited to young people. I can’t tell you how many times my 80-year-old mother would send me an email forwarded from my brother or other people her age that contained what we now call “fake news”. You know, those emails defaming people because of the flag, religion, race, NRA, politics, etc.

And I would spend about 20 seconds checking Snopes or Politifact and send an email back to my mother and the sender of the original email with the findings. And usually, I’d get a response of “don’t bother me with facts, I know this is true”. In some cases, if I was the direct recipient and the sender had a huge list of TO:, I’d reply all. Just to try to contain some of the crap. My brother still won’t speak to me because I “embarrassed” him to his friends by fact-checking a racist email he’d sent out.

Unfortunately, with the speed of Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, etc. it’s becoming harder and harder to check these things.