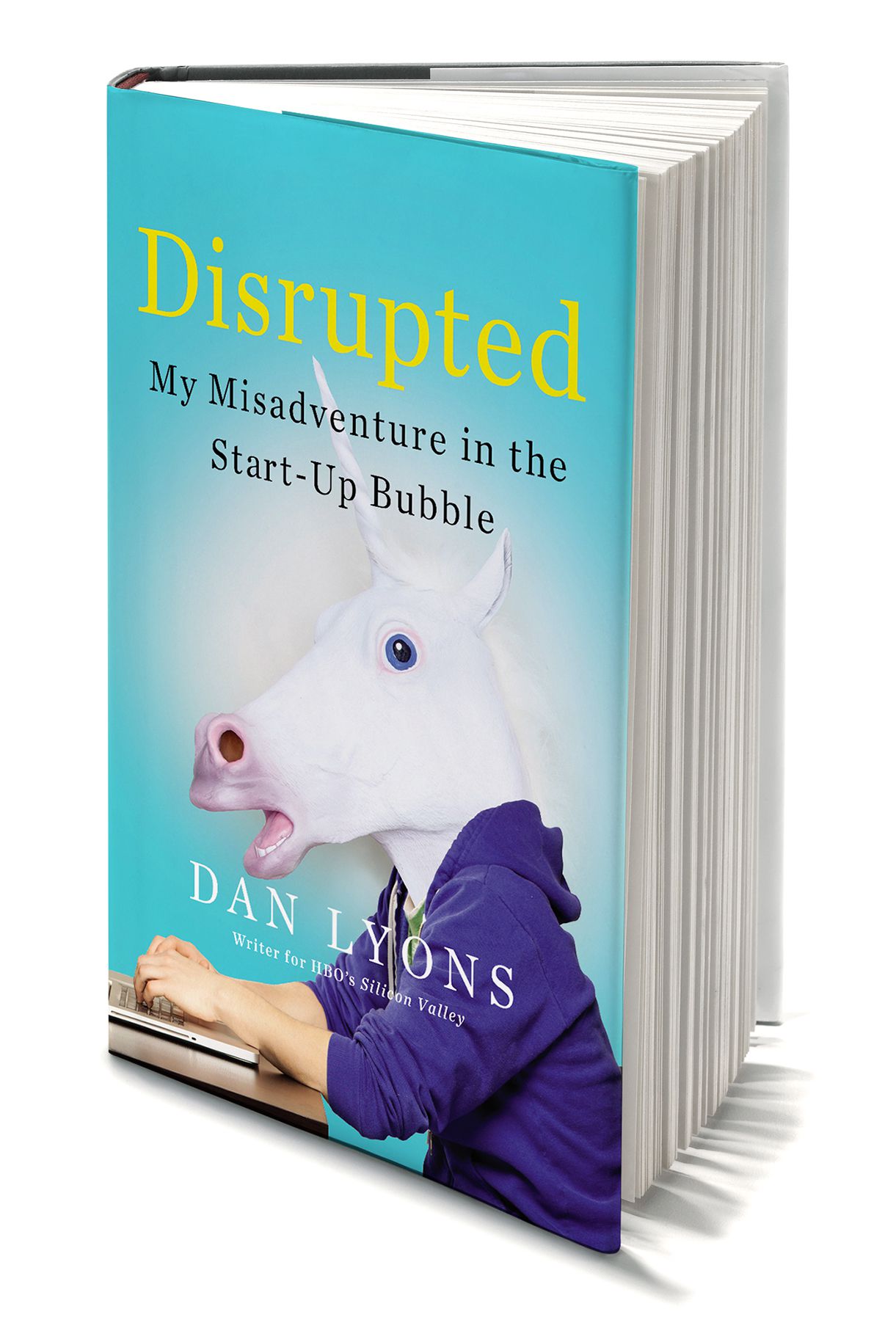

Lessons from the Dan Lyons HubSpot fable “Disrupted”

You should read Disrupted, by Dan Lyons. And you should take notes, because this is not just a story about startups, culture clash, and the technology industry. It’s full of lessons for every worker and every business.

You should read Disrupted, by Dan Lyons. And you should take notes, because this is not just a story about startups, culture clash, and the technology industry. It’s full of lessons for every worker and every business.

My post is biased, because I know nearly everybody involved here (for full disclosure*, see the end of the post). At first I thought that meant I should stay out of it, until I realized it actually meant I should wade in. I interviewed Dan, got email responses to my questions to HubSpot, and spoke off the record to other people familiar with what happened.

Disrupted is a fascinating view of culture clash

Dan Lyons is an awesomely talented storyteller and smartass. He was the Fake Steve Jobs and wrote a book on that. He’s a writer for HBO’s Silicon Valley.

Disrupted: My Misadventure in the Start-Up Bubble is a diverting and revealing story, vividly told. Dan starts by losing his job as technology editor at Newsweek and, soon after, leaving a management position at ReadWrite. At age 52, as he puts it, “Losing my job sent me into a tailspin.” So he interviews with Brian Halligan and Dharmesh Shah, the leaders of HubSpot, a “powerful, easy to use, integrated set of applications for businesses to attract, engage, and delight customers.” In other words, HubSpot makes cloud-based marketing tools.

HubSpot focuses on inbound marketing, which means activities you undertake to draw customers to you, such as blogging and social media. HubSpot also helps small and medium-sized companies to manage the leads which that activity generates, nurture them, and sell to them. The CMO hires Dan as a marketing fellow, to write blog content and advise management.

The best thing about this book is the nakedness of the story. Dan holds nothing back in his descriptions of his coworkers and, most importantly, in his description of his own feelings and emotions as he goes though this epic saga. It’s written in the present tense, which makes it feel more real.

Disrupted is a tragedy. Dan finds HubSpot filled with enthusiastic, inexperienced workers, nearly all white and very young, who operate in an orange-colored frenzy of passion for the company’s mission. The senior managers who hired him don’t have time to manage him; somebody much younger ends up as his boss. They can’t figure out what to do with him; he’s overqualified for everything they throw at him. He hangs onto the job for appearances, having a salary, and health insurance.

The hinge of this story is culture clash. HubSpot is about moving fast, growth, and a go-go culture that, as Dan tells it, values enthusiasm and “teamwork” over efficiency, strategy, or profit. Dan is an experienced journalist whom the rest of the workers just can’t seem to puzzle out. He’s got a wife and kids, while they’re hard-charging “bros” and young women who all seem to wear the same clothes and have the same haircut.

Dan’s perceptions of the misunderstandings, personality clashes, bizarre incidents, social media faux pas, and HubSpot’s cult of belief make the story come alive. And when the fun is over and he finally leaves HubSpot, there’s even an epilogue about an FBI investigation of people allegedly attempting to hack computers and steal the manuscript.

Is it true? The facts match what I’ve seen. But everyone has their own perspective on the truth. People who were there tell me that context is missing. Dharmesh has written his own rebuttal.

HubSpot has a dedicated customer base and its products have a lot more value than Disrupted implies. (They claim revenue retention exceeded 100% for 2015, which implies happy customers — upsell is exceeding churn.) But I have no trouble believing that the chaotic environment Dan describes was real.

If you want to decry age discrimination in technology, lack of diversity, profitless startups, stupid investors, greedy VCs, bubble mentality, and the venality of technology leaders, you can fuel your concerns with this book. But I don’t think whining — or this book — will change much; the current system is making a lot of money for a lot of people and churning out successful innovations from Facebook to Tesla to Uber, employing millions. It’s a terrible system that chews up people like Dan and leaves the rubble of broken startups littering the landscape. That’s just how it works.

But you can learn from this. Dan made plenty of mistakes (and fearlessly documented his own failures here). And HubSpot did a bunch of stupid things, too. So after you’ve finished this entertaining story, don’t just smile. Do things differently.

What you can learn from Dan Lyons’ experience

Here’s an incomplete list of what Dan did wrong, with some of his commentary from our interview.

Here’s an incomplete list of what Dan did wrong, with some of his commentary from our interview.

- Don’t ignore your actual talents. I was amazed that Dan felt such a strong need to line up a “real job” — a situation that I suppose a lot of journalists are in about now. As he said to me, “Without a job, who are you?” The most important lesson here is to make sure you have an answer to that question. Dan Lyons actually had a great answer — he’s a wicked funny and insightful storyteller — and he ran away from that answer until Silicon Valley came calling.

- You are going to lose your job, so prepare. You’re going to get laid off or fired. The time to polish up those contacts, update that Linked In, and put aside a bunch of money is when you’re happily employed. Then you won’t feel so desperate. (Even if you don’t lose your job, you won’t regret the preparation.) As for the 52-year-old thing — there are plenty of companies willing to hire a clever and flexible person in that age range. But you’ve always got to be thinking of how you’ll make it, because the warm bosom of your employer and your cozy desk at work won’t always be there.

- Check out the culture before jumping. Dan explained to me that several months after he took the job, a VC told him that everyone knew HubSpot had “a wacky fucking culture” and was surprised that Dan hadn’t been aware of it. You don’t find that out by interviewing the CEO, you find it out by digging around with the employees (a skill that a tech reporter should have). Don’t do this, and you could end up miserable (and unlike Dan, you probably can’t write a book about it). As he says in the book, “It’s turns out I’ve been naive. I’ve spent twenty-five years writing about technology companies, and I thought I understood this industry. But at HubSpot I’m discovering that a lot of what I believed was wrong.”

- Don’t crap on the senior leadership, especially publicly. At one point, Dan posts on Facebook about Brian Halligan’s ageist quote in a New York Times interview: “We’re trying to build a culture specifically to attract and retain Gen Y’ers.” Then his bosses and HubSpot PR have a fit. Look, I don’t care if you only post for your friends, social media is public, and you can’t dump on the CEO. As Dan told me “That was a kamikaze thing. I just should have known better.” Yup.

- Back up your ideas with politics and lobbying. At one point, Dan brings an awesome idea to Brian and Dharmesh about a high-end blog for thought leadership. As he tells it, they agree, some time passes including a vacation for Dan, and then he comes back and the commitment to the idea has vanished. Speaking as someone who has done some unusual things at companies I’ve worked for, that’s not how you make change happen. You have discussions, you line up allies, you get it in writing, you fend off challenges, and most of all, you get budget committed. Dan had the right idea, but didn’t work the politics.

- Loyalty is bullshit. Dan finds it chilling when his boss (not the original guy, but a more senior one they brought in) says, about his potentially being fired, “The company doesn’t need a reason to fire you. The company can do whatever it wants.” The truth is, unless your contract has a time commitment in it (and most don’t), you are an “at will” employee — of course they can let you go. Feel free to be as loyal to a company as you want. But don’t be shocked when you lose your job — their loyalty goes only as far as company economics and the whims of your managers.

- Don’t count on your stock options. Stock compensation favors senior management and investors. Your options are likely to be worthless. If they pay off, great. If they don’t, that’s normal. I’ve experienced both.

- Don’t do anything scary on the day of the IPO. Dan makes a small joke on social media on the day of HubSpot’s initial public offering. HubSpot’s PR “overreacts.” But face it, an IPO is the biggest, most important financial and image moment a company has in its lifetime, and “quiet period” rules mean they can’t respond freely to statements about the company. I wouldn’t even criticize the CEO’s tie on the day of the IPO. Pick another day to be a smartass.

- PR people are people. “Spinner,” the main PR person at HubSpot, doesn’t trust Lyons and he feels humiliated to have to apologize to her. In my own experience, PR people are image experts and you have to respect that — and they get so little respect that they really appreciate people who notice the work they do. And in the end, Spinner was right about Dan, who took a huge dump on the company’s image in the form of this book.

- Don’t write a book. You’re not as talented as Dan. But if you do write a book, and the company miraculously doesn’t sue you, nobody will hire you in your next job. They don’t want to be featured as “Trotsky” or “Cranium” in your next book.

What companies can learn from HubSpot’s experience

A lot of the criticism and absurdity in Disrupted hits home. If you help run a company, don’t just laugh at this. Learn from it.

A lot of the criticism and absurdity in Disrupted hits home. If you help run a company, don’t just laugh at this. Learn from it.

- Diversity is not just a hoop to jump through. HubSpot sounds like a fun place to work, and boasts a raucous culture and an impressive net promoter score for its employees. But HubSpot’s homogeneous culture of young, inexperienced white people, as Dan describes it, leads to blind spots. (Dharmesh says they’re working on fixing it: “We already have programs in place to improve diversity and we’re making progress. But there is much more work to be done.” ) A diversity of people — including minorities and older workers — will save you from a lot of stupid mistakes.

- Explain the path forward, honestly. One of Dan’s biggest criticisms, not just of HubSpot, but of the whole technology business, is the focus on growth over profit. In the end, every business needs to make money. But investors will support a plan that prioritizes growth over profit, as long as the growth continues. In the end, HubSpot needed to make it clearer to people like Dan how the path they were on would lead to either (1) a profitable endgame or (2) acquisition by a company like Adobe or salesforce.com. Nobody at HubSpot talks about acquisition, but it’s one way companies like this end up.

- Go easy on the company jargon. It’s clear from the book that HubSpotters used their own special language to encode the culture of the company and create an insider feel. I’ve seen this at lots of places — it works, to a point. But if somebody outside your company listens to you talk and can’t make head or tails of it, you’ve gone too far. Dharmesh admits that calling it “graduation” when somebody leaves the company wasn’t such a good idea.

- Give people severance. Dan describes people leaving in tears after getting fired. If you’ve been in a job for years, you deserve some time to get back on your feet. Give people some weeks or months of salary, depending on their tenure and rank, and you’ll damp down some of the ill feeling that such ex-employees tend to spread once they’re on the outside. (For the record, Dan says in the book that he got six weeks severance after working there for less than two years.)

- Make room for grownups. Just hire some adults and listen to what they have to say. If HubSpot tripled the number of people over 40, it would still be a very young company, but it might be better prepared for business success. It’s not a coincidence that young founders like Mark Zuckerberg hire experienced managers like Sheryl Sandberg to help run things.

- If you say you’re transparent, be transparent. Transparency is one of HubSpot founder and cultural leader Dharmesh Shah’s key tenets. But if there’s one thing this book shows, it’s that they’re not that good at being transparent — the company concealed a lot of things from its staff and and from Dan. That transparency promise is now in tatters. Workers will put up with a lot, but hypocrisy is deadly.

- If you make a high-profile hire, make it work. Until his new boss shows up, HubSpot’s attitude towards Dan borders on neglect. This festers, until he decides to make his time at HubSpot into an anthropology experiment and a book. This was a tragic waste of talent. If the people who had originally hired Dan had worked a little harder to get value out of him, there’s a lot he could have done there. It’s not all their fault, but recognize that if you’re in this situation, you’ve got a job to do to help your high-profile hire to succeed.

- For lord’s sake, don’t allow people you hire to write stuff like this. I’ve bridled under company confidentiality and noncompete agreements, but they did their job. Now I am wondering how people get to write stuff like Dan did. Can’t a company put a clause in their employment agreement that says you can’t write a book about your experiences? In any case, criticizing the company publicly (including on social media) is typically grounds for dismissal — so if you see people doing this, warn them and then fire them.

Disclosures*

I said I was biased, and I am. If you want to know my relationship with the people and companies in Disrupted, here’s a list of disclosures, which is rich with its own ironies.

- I’ve spoken with Dan Lyons several times and have been on panels with him. I even contacted him at one point to talk about content opportunities at HubSpot (which, given what I’ve just read, qualifies as theater of the absurd).

- I’ve had dinner with HubSpot founder Dharmesh Shah and have bumped into him and Brian Halligan at various functions around Boston. I’m friends with David Meerman Scott, who advises the company and has coauthored a book with Brian.

- I got a free pass to last year’s HubSpot conference and blogged about my experience in a post called “The Humble Disruptor.” (Any similarity to the name of Dan’s book is purely coincidental.) I will be applying to speak at HubSpot’s conference this fall.

- My first consulting gig after leaving Forrester was to edit a report for HubSpot. Some of the people I worked for are featured in the book. (I am not currently doing any work for HubSpot and don’t expect future work, although it’s possible.)

- I know and have friendly relationships with several senior people there including their media relations head Laura Moran, who previously worked for both Forrester Research and Harvard Business Press. Her jobs at those jobs included promoting my books. (Laura is not “Spinner,” that’s somebody else.)

- I know the Boston Globe reporters who broke the story last year about HubSpot employees allegedly attempting to procure the manuscript of Disrupted. One of them is the guy who invited me to dinner with Dharmesh.

Now you know. Please judge what I’ve written based on its content, but you deserve to know what biases I might have.

This is a really good, relatively objective analysis. Helps that you’re biased in both directions 🙂

A few thoughts:

1) Isn’t the desire to be transparent — even if not fully realized — contrary to using nondisparagement clauses and NDAs to keep former employees quiet? While I’m sure HubSpot COULD have come down hard on this, wouldn’t that violate the desire to have a transparent culture? Seems like a no-win.

2) It took me a long time to accept that lobbying for ideas at my company was important, but it is. When you have a small, simple team with a narrow focus it’s not necessary. But as a company grows there WILL be people with different ideas and priorities. Selling those ideas is part of being a senior employee. However, you also have to sometimes accept losing. If HubSpot isn’t a company going after the large-enterprise space, they’re not going to support a marketing initiative aimed there.

2b) THAT begs the question of hiring talented people and THEN trying to find a role, which is a common tactic in tech where talent acquisition is incredibly competitive. That’s one of the root causes here — someone who wasn’t a good fit for the needs for the team was hired because he was very talented, but then there wasn’t anything for him to do. It’s a rare occurrence that usually happens when someone is “internet famous” or has a particularly compelling skill set.

Not2b) because I can’t have a 2b without adding that.

3) Diversity is an issue for all of society, not just companies. As a hiring manager, it’s a difficult balance between wanting to actively grow diversity and being responsible to shareholders to hire the best available talent that’s willing to be where your offices are (probably a bigger problem than you’d think to get people to move to a frigid and expensive city like Boston). Companies need to be aware of and control for hiring biases (there are good ways to do that), but society needs to help them fill the pipeline by working on the achievement gaps in education and encouraging more occupational diversity. Hiring someone who’s unqualified because of what demographic they represent hurts the company AND the employee, because a failure wastes their time and makes it harder to land the next job. This is a critical area of focus for all companies, and good mechanisms exist for controlling for hiring biases, but there’s no easy and clear answer to the pipeline issue here.

4) On hiring “grownups”: Early-stage startups are HARD and likely doomed to fail. Your early team needs to be willing to work hard FAR more than 40 hours a week to have any shot at success. This tends to attract people who are young and don’t have families. It’s also one of the root causes of the playful office — I’m far more likely to be willing to work 60+ hours if my office is actually more fun and more relaxing than my apartment (and has a better beer selection). The key is to bring IN “grownups” (here defined as experienced people who expect a work/life balance) once you scale and have enough people and consistency that every single email isn’t a critical emergency. If there’s a startup that grew to be successful with no one ever working more than 40 hours a week, I’d love to know their secret.

5) Related to #4, stock options decrease in value as a company grows and takes more rounds. Early employees working crazy hours to make it happen usually make out REALLY well, but if you come in after 5 rounds of fundraising (as one of those work/life balance folks) your stock options may be enough to cover the down payment on a house but not much more. Which, to be fair, is still a better benefit than most people have available to them these days.

Great post, Josh. There’s a lot to which I can relate, here. I’ve been a successful digital leader, strategist and communicator for 20 years, but I’ve seen and felt many of the things that Dan has about ageism and insular cultures. I’ve bristled at companies that make really silly mistakes in social media and marketing, and (right or wrong) suspect it is because too many companies value enthusiasm and youth more than experience and maturity.

The only point on which I might disagree is when you say “the current system is making a lot of money for a lot of people.” I do not think this is true–the current system makes a lot of people paper wealthy for a while but has proven to leave few people with “a lot of money” in the end. We saw it in the dot-com bubble, and we’re seeing it again now with the over-investment and subsequent down-rounds in tech. (You allude to this later in your article when you mention–correctly–that people should not count on their stock options. )

My point is that maybe there is something we ought to learn here beyond what you suggest–that perhaps there is a different leadership, culture, hiring and organizational mentality that ought to be considered by tech (and agencies and even Fortune 500s). Perhaps we could learn not just from Dan’s book but from the repeated mistakes made by startup leaders who act like the gravy train will never end, by investors (particularly of the late-round variety) who seem more motivated by hype than actual financial analysis and by employees who have stars in their eyes but often are left with only modest sums in their pockets.

One lesson is that organizations do need a variety of people and that experience and leadership matter. Another lesson is that what gets your budding business to your B and C round is not what gets it to long-term stability, profitability and success. Another lesson may be that we ought to be A LOT less excited about VC-fueled valuations and a lot more excited about the hard work of building a profitable, stable business model.

You provide great advice, but I think there is something deeper to be said about the value of leadership–the kind that succeeds not just in the hype machine of the startup world but that builds something that lasts and changes lives for both employees and customers.

I’m really glad you wrote this since you confirmed my instincts about the book (major culture clash, poor communication) after reading the nytimes review. While I’m extremely curious to read the book, I didn’t want to purchase it and thus support the author’s vindictive message, especially since I’m a really happy Hubspot user and advocate. Still curious to read it, however 🙂

Hi Rebecca, I read the book and you are right to think that some of it is vindictive. It is. And journalists sell more papers by creating outrage and scandal. So it’s never going to be ‘my fun time at..’

But it’s worth a read, there’s lessons to be learnt. Not just about culture clash etc.

It’s more insightful than that.

It really challenges a broader segment of the digital industry – Hubspot is just the case study.

It got me thinking about marketing and authenticity…! And people.

But before that read ‘The Fourth Industrial Revolution’, by Klaus Schwab.

Klaus gives the world view and Dan gives the worker view.

There’s always your local library.

I was really keen to read this blog post because the blog is called ‘without bullshit’. But I come away thinking that, to spare the b.s., this post is using b.s. to justify b.s.

‘That’s just how it works’ is just not good enough.

…. don’t just read the book and learn how to play the game better.

Get mad, change the game.

A bit of anectdotal insight might be in order for balance here, and as an aside from what the relationship between an ambitious startup in a niche market can or should do with experienced (and in the article perhaps alluded to as), wasted talent, here are some obvious observations.

Changing the perceived landscape of a tangible geography bolsters, and creates a cult-like atmosphere in the workplace, and yet ultimately, a spade is still a spade – we all want a fun workplace, yet it is still work, and a lack of real vision will only go so far in saturating a market until the mundane nature of real work begins to erode the facade of inventive culture.

We’re talking about a company and a former employee of that company whose business product that focuses on a very understood and moving target – driving internet web traffic to a customers product and helping them to drive sales. This is a model that has overshadowed focus on the customer’s actual product itself, with zealous attention to bringing in prospects regardless of whether that customer has a viable business offering.

That is okay, because, as a provider of a service in a b2b relationship, it isn’t our responsibility to care whether a customer’s business product is viable, but rather, to deliver our service to the customer availing them of leads from which they can close their own deals.

In the long run, the customer will appreciate unprecidented financial windfalls or flounder depending upon whether their business product had intrinsic value.

Although the value of this particular b2b service can be measured initially in terms of immediate results, their customers will sink or swim based on the value their consumers perceive.

Considering that the business of driving people to a sales force is a bit of psychological guesswork and informed estimation, the book by Dan exposes a severe problem in the post dot com bubble world – that we haven’t learned our lessons about startups and corporate culture and deft funding by venture capitalists. We simply must, at some point, take the business of doing business seriously.

How much guitar strumming on our own strings has been implied in this blog post by the parties on both sides? And how much forward vision on where the company is going to go when the tides change has been invested?

I once wrote a web based application called, “Spyderbait”, which was, upon general release, extremely successful and exceeded my wildest expectations in terms of both sales and its effectiveness in driving “inbound marketing”.

It was so successful that the small company which I was the CTO of could not handle the myriad of different industry sectors that were interested in having search engines throwing traffic at them in the form of potential clients.

Fortunately, this was not the only focus of our business and that was but one business product we produced, having the benefit of a CEO whose (dare I say) age, wisdom, and experience mandated that we not put all of our eggs into one basket.

At the time, being a young man, about as experienced in business as the vivid description of the employees in Dan’s book, I saw myself as retiring on this one script – while he refused to allow any of us to not look toward the future.

One day, I was awakened by a very frantic employee (one of my junior admins), stating that the phones were ringing off the hook because what appeared to be all of the customers of this product were livid, finding that none of their websites were listed any longer in any of the search results at the search engines.

What I charged my customers almost a thousand a month for stopped working.

Things change, and if there’s a lesson to be learned from the book, from the company he worked for, or the industry itself, is that things change, and I don’t think there’s a single financial advisor out there who won’t urge you to diversify your portfolio.

Enthusiasm will take you a long way as long as you don’t become complacent and think that you should disregard diversify in both the focus of your business and the enrichment that this same sort of diversity in employee demographics.

Not utilizing a valuable resource with respect to an employee was pointed out as one of the failings of this company, and not valuing the notion of some modicum of respect for the company was pointed out as one of the failings of the author – somewhere in between lies the answer to whether a company such as this will survive the changing nature of social networking.

“For lord’s sake, don’t allow people you hire to write stuff like this. I’ve bridled under company confidentiality and noncompete agreements, but they did their job. Now I am wondering how people get to write stuff like Dan did. Can’t a company put a clause in their employment agreement that says you can’t write a book about your experiences? In any case, criticizing the company publicly (including on social media) is typically grounds for dismissal — so if you see people doing this, warn them and then fire them.”

This is horrific. Employers already have a great deal of influence over their staff; they control pay, health insurance, retirement plans, etc. You want to give them control of employees even after they quit? Abusive employers get away with their nonsense, in part, because no one knows they are doing it. Confidentiality agreements are another way for these businesses to get away with mistreating their staff.

Look, Lyons made some missteps, but can you really blame him for calling out Halligan’s admission to the New York Times that HubSpot discriminates on the basis of age? Or should we all be silent about such things? If Halligan had said the same thing about black people no one would defend him, nor should they.

Also, I just can’t take seriously a company in which its founder not only brings *a teddy bear* to meetings–and talks to it!–but is lauded as an “innovator” for doing so. I don’t know how anyone else can, either.

I think Dan Lyons is awesome and he crushed it with his book!!!!!!!!! I also think he exposed a lousy company that takes advantage of a bunch of inexperienced people. The bros at the helm seem like major douchebags too. Loved the book.

“Can’t a company put a clause in their employment agreement that says you can’t write a book about your experiences?”

Absolutely no. This is a violation of freedom of speech.

Freedom of speech says the government can’t stop you from speaking. It doesn’t say a company can’t.

It’s common for companies to restrict speech of employees after they leave with confidentiality and non-disparagement clauses.

If HubSpot had done that, this book would not exist.

Without Bullshit? Sorry, this blog post was pure bullshit. I’ve worked in tech for 30 years–not in marketing, nor PR, nor any of that fluffy crap, but in IT, doing the actual work that people like these douchebags in this book take and turn into riches for themselves. The bottom line is these “disruptive” technology companies are poorly run, exploitative, and border-line criminal, operating fast and loose in gray areas that I am now inclined to believe need to be turned into no-go areas. We need a Teddy Roosevelt for a new digital robber baron era to ram a big stick up the self-righteous ass of companies like HubSpot with strong legilation that makes illegal most of these business practices, including going public without a profit in sight. These people aren’t working on a cure for a disease; there is no justification for “go public or go broke.” There is no reason that pensioners and other investors should be putting money in the pockets of these charlatans who can’t even handle day-to-day tasks properly.

And there is no excuse for your defense of them. I will goddamn live as I see fit and do my job as I see fit, and not be told I am here to kotow to trash like this just because they were lucky enough to be my boss. Your right to be treated decently doesn’t end just because you pay my wages. Your apology for them makes you as scummy and useless as these people. Hey, maybe they’ll reward you with a job. You’d fit right in, shitting all over people like you know more than them. I don’t think Dan needs your advice. Nor any of us.