Discovering emptiness — why I feel for Ernest Rutherford

In the early 1900s, the physicist Ernest Rutherford discovered the emptiness at the heart of everything. In 2015, so did I.

Ernest Rutherford, born in New Zealand, was an early experimenter in the field of radioactivity. Working at the University of Manchester, England, he investigated the mineral uranium and the stream of particles it emitted, which he called alpha particles. He and his assistant, Hans Geiger, could actually see and count the particles, which appeared as flashes of light as they smashed into a screen of zinc sulfide. (Perhaps the tedium of counting the flashes led Geiger to invent a more convenient device for detecting radioactivity, the Geiger Counter.)

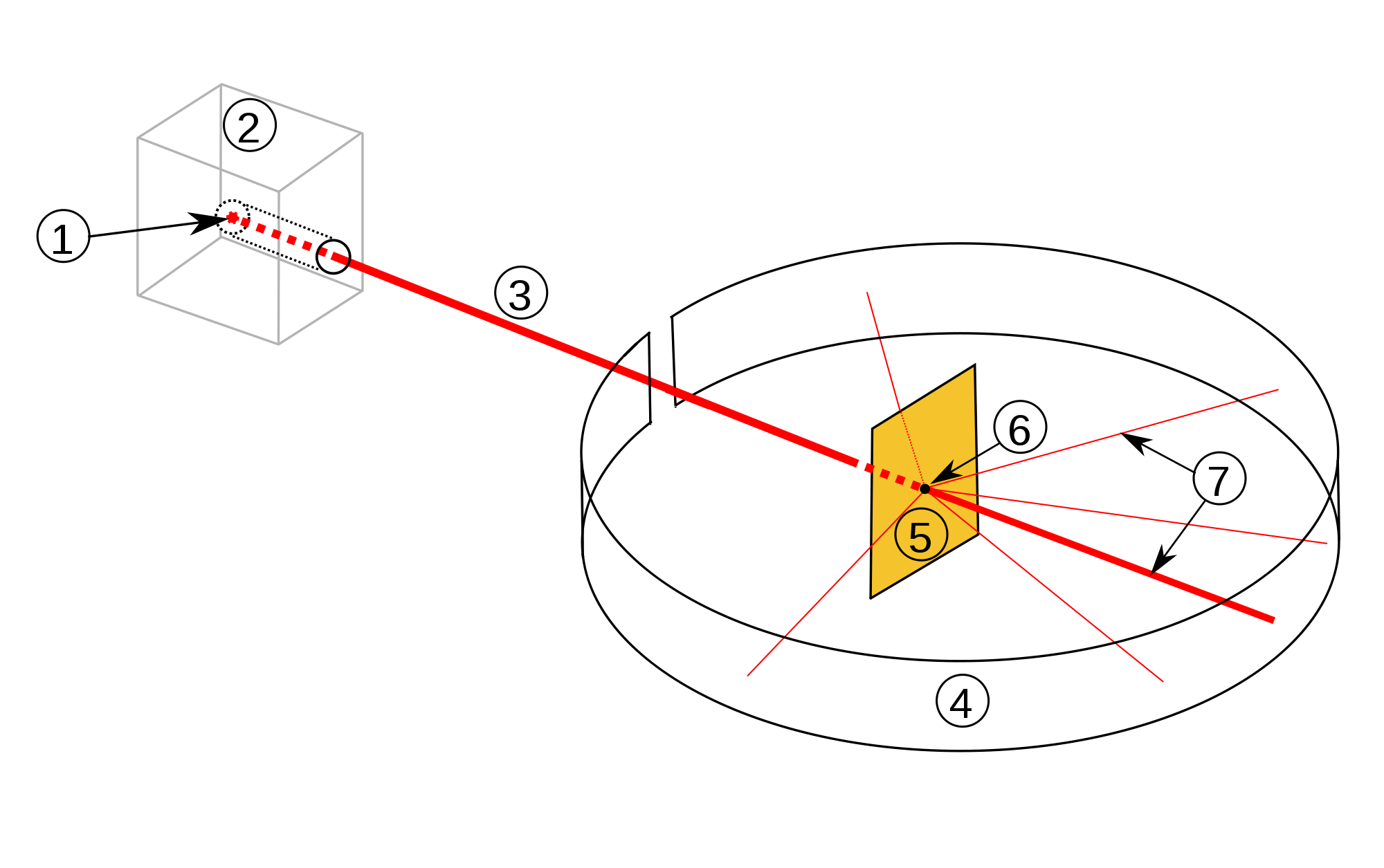

Like any good scientist, Rutherford wanted to put his knowledge of radioactivity to work. What would happen if you shot alpha particles at matter? Could you see what was inside it? So Rutherford, Geiger, and grad student named Ernest Marsden conducted an experiment. They put an extremely thin sheet of gold foil (4 millionths of a centimeter thick) in the path of the alpha particles. They put the zinc sulfide screen on the other side. Then they monitored the flashes to determine if anything inside the foil was changing the path of the particles. Here’s a picture of the experiment; the red line is the beam of alpha particles.

Scientists at the time knew about atoms, but had no clear idea of what was inside of them. If, as most of them thought, the mass and charges inside the atoms were basically all mixed up — this was called the “plum pudding” model — then the alpha particles would shoot right through or be only slightly deflected, and the experiment would prove that.

But that’s not what happened.

Ernest Rutherford discovers nothingness

The results of the experiment were not at all what Rutherford expected.

Most of the alpha particles went straight through the foil, completely unimpeded. But about one in 8,000 of the particles rebounded at an angle of greater than 90 degrees. Given the speed and energy of the particles and the thinness of the foil, this was an astounding result. Here’s what Rutherford said at the time:

It was quite the most incredible event that has ever happened to me in my life. It was almost as incredible as if you fired a 15-inch shell at a piece of tissue paper and it came back and hit you. On consideration, I realized that this scattering backward must be the result of a single collision, and when I made calculations I saw that it was impossible to get anything of that order of magnitude unless you took a system in which the greater part of the mass of the atom was concentrated in a minute nucleus.

So Rutherford had discovered that nearly all the mass of atoms is concentrated in a tiny space in the middle — the nucleus.

What made up the rest of the atom? Absolute vacuum. Nothing. Space. (Eventually they figured out that there were a few tiny electrons whizzing around, but as far as mass, nearly all of it is in the tiny nucleus.)

Imagine that you are Ernest Rutherford figuring this out. You look around you. There are tables, chairs, floors, people, notebooks, all the solid and real things that make up the world. And you have just discovered that all of it is made up, for the most part, of empty space. The solid floor: empty. The chair you’re sitting on: empty. The world is full of nothing, with tiny pinpoints of mass scattered throughout.

My Rutherford moment

In March of 2015, when I left my job and considered what to do next, I started to think about the text we all read every day. And I started to take a close look at that text, to deconstruct it and see what it is made of.

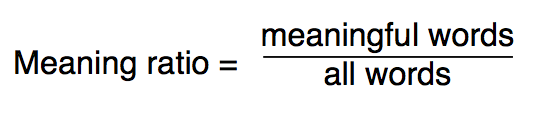

Each of us at the end of a day has the uneasy feeling that we have consumed a lot of writing, but that it is not all that filling. I asked why. And I developed the idea of the meaning ratio — the ratio between the number of meaningful words in a piece of text, and the total number of words.

As I applied this metric to what I read, I found something that astounded me as much as Ernest Rutherford must have been astounded. Much of what we read has no meaning. It’s as empty as an atom. There’s meaning there, in a tiny nubbin in the center, but it’s surrounded by massless fluff.

Rutherford’s discovery changed physics forever. I am just at the beginning of my journey, and it will never be anywhere near as consequential as Rutherford’s. But I know how he felt. I know the experience of realizing that most of what we perceive is not nearly as solid as it seems. I want to know why, and I want to know how it affects people.

This is the start of the talk I will give at the PRSA conference in Indianapolis on this Sunday, October 23. Drop by if you want to hear the rest.

That’s why I read and write poetry–it’s almost all nucleus! At least in the best poetry. Outside of poetry and fiction, in so much of our public discourse, this analogy applies perfectly.

With your article, you have demonstrated an ‘own goal’ with respect to the Meaning Ratio.

The work of Claude Shannon may be more relevant to characterizing bullshit than your attempt to bask in the reflected glory of Ernest Rutherford.

First post of yours where the Meaning Ration is inverted.

Love to drop by, but Indianapolis is a long way from Sydney!

My initial reaction is that comparing the space in atoms with writing does not hold up.

The space in writing would be BS and you are a no BS guy.

Dan

As a former engineer and present writer, I can embrace the MR concept. It’s simple and makes the point. (Separately, during my tenure at Cornell University, we had a solid hockey player by the name of Geiger; we enjoyed counting his goals;^)