Could ranked choice voting save us from the “least objectionable candidate?”

In Maine, you’re now allowed to indicate your second choice on your ballot — and with “ranked choice voting,” your second choice might make the difference in who is elected. We’re considering it in Massachusetts, too. Let’s take a look at how ranked choice voting works, and how it might save us from elections with two unpalatable choices.

What is ranked choice voting?

In ranked choice voting, also known as “instant runoff,” each voter can indicate their first, second, third, and possibly other choices for each race. In any given race, if the leading candidate does not have a majority (50% plus one vote), then the vote tallyers look at all the ballots from the last-place candidate, and distribute those votes to whatever candidate they indicated as second choice. If there’s still no majority winner, the new last-place candidate’s votes get distributed to the second-choice votes on those ballots. This continues until one candidate gets a majority — that candidate is the winner.

Unlike the current system in most locations, in which the candidate with the most votes wins, ranked choice voting ensures that the winning candidate has majority support. It also reduces “strategic” voting in which people who prefer a given candidate decide to vote for somebody else because they’re worried their candidate can’t win.

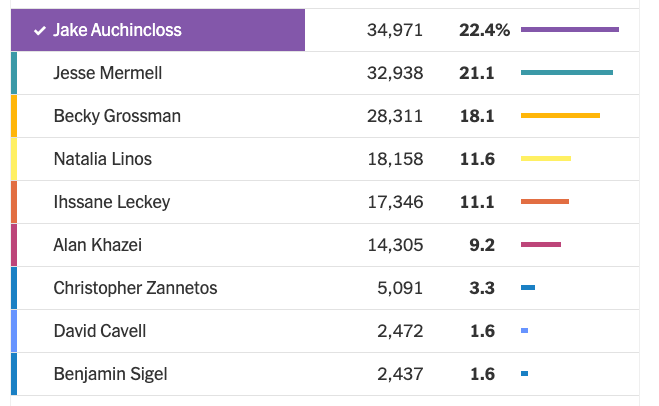

Here’s an example of an election that ranked-choice voting could have helped with — the primary for the Democratic nomination to succeed Joe Kennedy as Representative for the Massachusetts Fourth Congressional District. Here are the final vote results:

As you can see, Jake Auchincloss beat Jesse Mermell by about 2000 votes, or 1.3%. But Auchincloss received less than one-fourth of all the votes. In this race, David Cavell and Chris Zannetos actually dropped out close to the election and endorsed Mermell. If their supporters had all actually voted for Mermell, she would have won. Ranked choice voting could have delivered a majority of votes (including second choice votes) to one of the candidates.

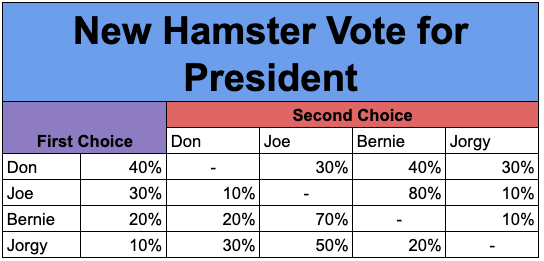

Let’s see how this might work in a general election campaign. You’re voting for president in an imaginary state called New Hamster that uses ranked choice voting. There are four candidates: Don, the Republican; Joe, the Democrat; Bernie, the Democratic Socialist; and Jorgy, the Libertarian. (Any resemblance to actual candidates is for amusement purposes only.)

When the final votes are tallied, here’s how the first and second choices look:

If you look at the columns under “First Choice,” you can see the results if this were a traditional election. The percentages under “Second Choice” show the distribution of second-choice selections of the voters backing each of the candidates.

In a traditional election, Don would win, because he has the most votes, 40%. But Don does not have a majority. So we need to eliminate the last-place candidate, Jorgy, and redistribute her votes to Don, Joe, and Bernie. In this case, Don gets an additional 3% (that is, 30% of Jorgy’s 10%), Joe gets an additional 5%, and Bernie gets an additional 2%.

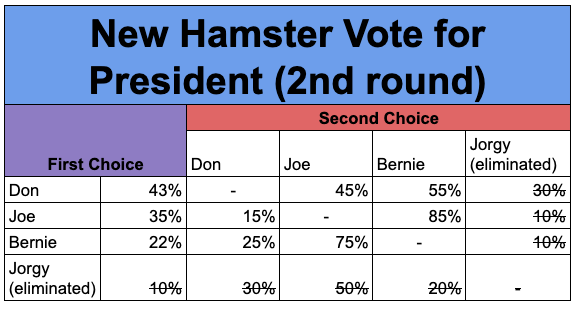

So in the second round, the chart looks like this:

Once we eliminate Jorgy from the race, her votes go to other candidates. Also, in any case where she was the second choice on someone’s ballot, now we need to get a new second choice (whatever candidate was previously listed as the third choice). This accounts for the slight shifts in both the First Choice and Second Choice parts of the chart.

No candidate has a majority, so again we need to redistribute votes for the new last-place candidate, Bernie. Bernie contributes 5.5% (that is, 25% of his 22%) to Don and 16.5% to Joe.

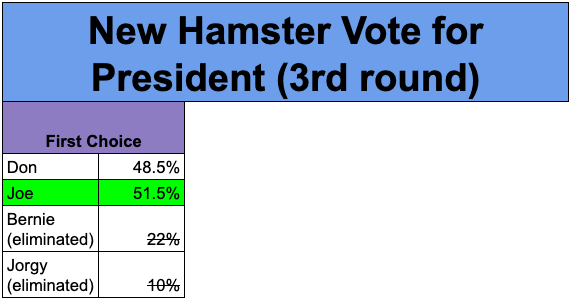

So the final tally looks like this:

Joe wins the presidential election in New Hamster with a majority of 51.5%.

Is this fair? After all, Don got more votes in the first round.

That’s true, but look at how Joe won. He got 30% of the first choice votes and 21.5% from second choices from Jorgy and Bernie. Don, on the other hand, got 40% of first-choice voters but only 8.5% from second choices. Clearly, Don is a polarizing candidate, because very small numbers of voters for other candidates are willing to choose him as a second choice. But Joe is more of a unifying candidate, since he appeals broadly to voters for other candidates.

Joe will be able to govern knowing that a majority of voters back him at some level. In the old system Don would have won, but would not have the support of a majority of voters.

The end of the “least objectionable candidate”

In the early days of television, programmers created the idea of the “least objectionable program.” In any given time slot, viewers watching TV would choose the program they liked best — or in some cases, disliked least. The only thing a program needed to do to win the time slot was to be better than whatever crap was on the other channels. (Large numbers of choices on cable, and then on-demand viewing, made this concept obsolete, of course.)

We remain in the era of the “least objectionable candidate.” Realistically, in nearly all general elections in America, only two candidates can have a reasonable expectation to win. Votes for other candidates are “protest votes” that indicate disgust with the system, but don’t contribute to the final result of the election. As a result, many people hold their noses and vote for the lesser of two evils — the “least objectionable candidate.” “What else could I do?” they ask. But their faith in the system and the parties continues to erode.

In primary elections like the Massachusetts Fourth, we have the opposite problem. Candidates can win with minimal support — they only need to do better than everyone else. The result is candidates who may actually be objectionable to a majority of voters in the district.

Ranked choice voting eliminates both of these problems.

Voters are free to vote for candidates that they don’t expect to win, knowing that their second choice votes will still help elect someone. They can thus register their preference in a measurable way without inadvertently contributing to the election of someone they despise.

Elections in America in 2020 are, for the most part, a zero-sum game. This contributes to negative campaigning. You win by making sure people won’t vote for the other person.

With ranked choice voting, negative campaigning is less effective. Instead, you win by appealing to voters who might favor another candidate. You’re better off getting the second choice on those ballots than alienating those voters completely. This means that candidates with broad appeal are more likely to win, which is, after all, the objective of democracy.

Our current electoral system disfavors third parties, because they are seen as “spoilers” whose only role is to draw votes away from a major candidate, helping to elect that candidate’s rival. But in a ranked choice voting system, third parties can gain influence and more easily sway the agenda of a major party. Not only that, if such a third party were to become more popular — especially if its positions are more moderate than those of either party — it could actually rise to displace one of those major parties. Or there could be a future in which three or more large parties are all viable, winning local elections in different states.

Does ranked choice voting have a chance?

Election rules are set in localities and states. As a result, the rise of ranked choice voting depends on changes on a state-by-state basis.

When it was put forth in Maine, it survived a number of court challenges. It’s a ballot question in Massachusetts in 2020. It has been used in local elections in Cambridge, Massachusetts since 1941, and is also in place for local elections in Berkeley, Oakland, San Francisco, and San Leandro, California; Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Santa Fe, New Mexico. New York will begin using it locally in 2021.

The main drawback of ranked choice voting is that it is slow. Sometimes it takes a few days to determine the winner of an election. It’s also confusing until people get the hang of it. It requires voter education.

In 2020, if you vote for president, you may be excited about the candidates — or you may be choosing the one that is least objectionable. If you are like me, you believe the political parties deserve some competition, and more candidates deserve a chance to make their case to the voters. So long as the person with the most votes wins, even if they do not have a majority, we will be stuck with an unresponsive and repressive two-party system. Ranked choice voting deserves to spread. It’s a better and more nuanced way to tell the people in power what we want.

Thanks for this excellent explanation of rank choice voting, with helpful examples. I really hope it passes!

Ranked choice is the only approach that makes sense. And it enables the development of real third parties. The alternative is to frequently end up with a candidate a majority of people voted against. When I lived in MN we ended up with a pro wrestler governor.

A fine explanation of ranked choice voting, a voting system that enhances democracy by making all votes more relevant and encouraging more citizens to vote. Obviously, as you point out, this will take a national state by state movement in which the details and its meaning must be conveyed clearly, but, in doing so, this could bring citizens closer together to support democracy regardless of their ideology. There must be a lot of retired teachers, among many others, who would love to participate in this political act that is fundamentally important for our democratic system yet nonpartisan.

If you want to explore different voting schemes, you could ask a Political Scientist. To keep it short: Different votings schemes can produce different results, including results that are absurd, that is, do not meet the smell test.

I can explain more, if you’d like, but ANY political science student ought to be able to help out.

If you want to read further, find Ken Arrow’s 1972 Nobel Prize package or Gödel’s incompleteness theorems. They are sufficient to cause pause.

Note: I am not saying that a different voting scheme should not be considered, but I AM saying, it is not clear which one is better or best. And I am saying Josh, Tom, and Kenna are wrong. That is not an opinion, it is a fact.

Norman, you’re way off here. Your being a political scientist doesn’t make you right, any more than my mathematical and analytical training makes me right. I’m aware of the results that show that all voting systems have flaws (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arrow%27s_impossibility_theorem) and that it’s mathematically impossible to create a voting system that agrees with what might seem like simple laws.

The question is whether in practice, this system would generate a better result in more cases.

Gödel’s incompleteness theorem does not apply in this case. And that’s from a former logician who studied in the Ph.D. program in logic at MIT.

I love the passive: not saying “a different voting scheme should not be considered.” I’m saying we SHOULD consider it, active voice.

As for calling me and the other commenters wrong: let’s be clear. There are two kinds of statements in any piece of prose that is supposed to be nonfiction.

There are facts, for example, that ranked choice voting is in use in Maine, and that it survived court challenges. Or that in ranked choice voting, whoever wins will have support from a majority of those voting, at least as a second or third choice. There are many such facts in this piece. Are you calling any of them inaccurate?

And then there are opinions. Such as “Realistically, in nearly all general elections in America, only two candidates can have a reasonable expectation to win.” and “With ranked choice voting, negative campaigning is less effective.” You can disagree with such opinions, you can offer evidence to show that you think they are wrong. But you cannot state that it is a fact that they are wrong. An opinion is an opinion, not a fact, and is therefore not factually wrong unless you have ironclad evidence that contradicts it.

I am spot on.

First, do not talk to me, talk to any political scientist. All should confirm what I said. It is settled political science.

Godel is important here as Arrow’s theorem is a restating of Godel’s incompleteness theorems. Arrow basically made the leap that every voting system is a mathematical system; seems obvious now, but it was ground-breaking circa 1950. Godel said every mathematical system is flawed. Arrow said every voting system is flawed.

I retract my characterization of your opinion as incorrect. You said better, and I concede any system can be better to anyone, just not everyone. Better-ness is strictly an opinion. I am wrong and I apologize. It is still significant that results many will think are “not better” happen in ALL voting systems (there are scores of them in use in various organizations). You are welcome to think the Ranked Choice system is better. That is your right and your opinion.

The other commentators said 1) “ranked choice is the only approach that makes sense.” I think we can agree that statement is false. and 2) “enhances democracy by making all votes more relevant and encouraging more citizens to vote.” Again, false.

I used the active voice. I (subject) not saying (verb)… I can restate it as I, Norman, do want folks to consider all changes to voting schemes, but I caution that all schemes will result in strategies and will produce some results that are nonsensical.

In recent history, people most often use the “change the voting scheme” rally cry to knock the Electoral College and the two-party system. That is fine, but rest assured the two parties know how the Electoral College works and plan ALL of their effort around the system/scheme. If you change it, they will adapt. So, when people say, well if the Electoral College was not there, then the other guy, aka their guy, would have won, that is merely simplistic and not obvious, no matter how they might explain it. Same thing goes with real third-party candidates like Perot or Sanders. And when you change the system to make your guy win, you are often disappointed in future elections.

Dictatorships and Monarchies are the closest to a sure-fire way to ensure your guy wins. Single-choice systems are the only exemptions to Arrow (and Godel).

Very silly to put a comment up and say “Don’t talk to me.” If I’m not talking to you why are you commenting?

As for Godel, he said that every mathematical system has true statements that cannot be proven.

Arrow says that every voting system has flaws.

Sounds the same but that’s lazy thinking.

From Journal of social philosophy (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-9833.1994.tb00311.x)

“[Arrow] showed that there could be no decision procedure for aggregating individual preference orderings into a grand, overall social preference ordering. The result has been hailed by some as a sort of Godel Theorem of economics. It has seemed to many to have, if not the complexity of the Godel Theorem, at least the same astonishing counter‐intuitiveness.”

Not the same.

Thank you for conceding that my opinion is my opinion and not some fact you can call wrong.

I’m ready to try something new — because the parties dominating the current system are inadequate.

Silly is an opinion too. Certainly, you can talk to me. My point was “don’t take my word for it, take everyone’s word for it.” Every political scientist, will agree–there is no voting scheme that is perfect or non-opinionated “better” “best” or any similar adjective or its antonym.

Thanks for the Gendin opinion. I had not heard of him (he sounds like he was interesting, RIP) or that viewpoint (or the viewpoint that others connected the two). I’ll have to figure out how to read his work; I do not see much in a quick search.

I connected the dots in late 80s. Not lazy, just efficient. From Kurt’s and Ken’s work, you can get to a lot of places that now seem obvious or, worst, incorrect and are neither.

I agree on the something new. I am not sure which one to try (and we have to be careful as we cannot do much experimenting as folks will not stand for switching the rules every election just because the “best” choice did not win or the “worst” choice did).

Great article. We use this method in Canada with the Conservative party and have just elected a new leader Erin O’Toole using this method. Results and graphics are on Wikipedia “2020 Conservative Party of Canada leadership election”

A podcast taking a different viewpoint but ending in the same conclusion is Freakonomics “America’s Hidden Duopoly”.