What authors can learn from the IBPA hybrid publisher standards

If you don’t need an advance, there are a lot of good reasons to consider a hybrid publisher — a publisher who will produce and distribute your book for a fee. But the self-publishing space is rife with con-men and amateurs. That’s one reason the Independent Book Publishers Association has published a 9-point set of standards for hybrid publishers that live up to a high standard of quality.

If you don’t need an advance, there are a lot of good reasons to consider a hybrid publisher — a publisher who will produce and distribute your book for a fee. But the self-publishing space is rife with con-men and amateurs. That’s one reason the Independent Book Publishers Association has published a 9-point set of standards for hybrid publishers that live up to a high standard of quality.

I’ve now worked with more than dozen authors seeking to create influence with business books. When they find out that it’s going to take 15 months or more to publish their book with a traditional publisher — assuming, of course, that they get an offer — they’re often looking for an alternative.

While its easy to produce a book quickly and cheaply using Amazon CreateSpace, the result is a print-on demand paperback that’s only available at Amazon. For example, that’s what Shel Israel and Robert Scoble did with their book on augmented reality, The Fourth Transformation. But that model is insufficient if you want a hardback that will appear in bookstores and be eligible for bestseller lists. That’s where hybrid publishers come in.

How to think about hybrid publishers

I spoke with Maggie Langrick, the CEO of hybrid publisher LifeTree Media, who helped create the new standards. The IBPA wants to help people distinguish between hybrid publishers, which create a publishing imprint and publish to industry standards, and author services companies (also known as vanity presses), who will produce any kind of book regardless of quality of the work. As Langrick told me, “That is not the activity of a true publisher.”

Why is this distinction important? “Our primary goal is to serve publishers who wish to set up or run a hybrid publishing company by working to a set of defined standards, which we all accept and agree upon.” said Langrick. “This protects the legitimacy of the model, so those who are doing vanity press are not degrading the term.”

IBPA also has a secondary goal, which is to assist authors in making choices. A full-service hybrid publisher is going to offer services, like editorial and full distribution services, that an author services company will not.

From my experience, this matters. I have written and edited books published by mainstream publishers, such as Harvard Business Press and HarperCollins, as well as books published by hybrid publishers, including Greenleaf Book Group and (for an upcoming book), Mascot Books. I also edited Shel and Robert’s book published with CreateSpace. Hybrid publishers not only do everything a traditional publisher can do, they work more quickly and are more responsive to author needs. While you’ll make more profit per book with CreateSpace, you’ll get a more professional result — and a bunch of services you may not be able to easily do yourself — with the hybrid publisher.

Are the IBPA’s criteria the right standards?

IBPA’s criteria are here. They’re helpful, but they don’t match exactly what I expected. Let’s have a look at the nine hurdles they say a hybrid publisher must clear. For each, I provide my own perspective.

A hybrid publisher must:

1. Define a mission and vision for its publishing program. A hybrid publisher has a publishing mission and a vision. In a traditional publishing company, the published work often reflects the interests and values of its publisher, whether that’s a passion for poetry or a specialization in business books. Good hybrid publishers are no different.

The first criterion is the one I find least compelling. First of all, anyone can write a mission statement for their “publisher.” Suppose your mission is “Help authors create quality books.” Is this sufficient? I also question the idea that a publisher must have a mission and vision — the editorial vision of even traditional publishers is pretty muddy these days. So I don’t think this criterion is all that helpful.

2. Vet submissions. A hybrid publisher vets submissions, publishing only those titles that meet the mission and vision of the company, as well as a defined quality level set by the publisher. Good hybrid publishers don’t publish everything that comes over the transom and often decline to publish.

As an author, you want your book to be in good company. Greenleaf, for example, has said that it only accepts 10% of the submissions it gets, although they have accepted all the authors whose proposals I worked on. If you don’t want a selective publisher, you’re not really ready to publish a high-quality book.

3. Publish under its own imprint(s) and ISBNs. A hybrid publisher is a true publishing house, with either a publisher or a publishing team developing and distributing books using the hybrid publisher’s own imprint(s) and ISBNs.

A hybrid publisher’s imprint should mean something, just as a traditional publisher’s does. But you should also have the option to publish under your own imprint. My book with Greenleaf, The Mobile Mind Shift, came out under “Groundswell Press,” which was intended to be Forrester’s book imprint.

4. Publish to industry standards. A hybrid publisher accepts full responsibility for the quality of the titles it publishes. Books released by a hybrid publisher should be on par with traditionally published books in terms of adherence to industry standards, which are detailed in IBPA’s “Industry Standards Checklist for a

Professionally Published Book.” [link]

5. Ensure editorial, design, and production quality. A hybrid publisher is responsible for producing books edited, designed, and produced to a professional degree. This includes assigning editors for developmental editing, copyediting, and proofreading, as needed, together with following traditional standards for a professionally designed book. All editors and designers must be publisher approved.

These are the essential reasons to work with a hybrid publisher — to get a guaranteed quality result, working with professional editors and designers.

6. Pursue and manage a range of publishing rights. A hybrid publisher normally publishes in both print and digital formats, as appropriate, and perhaps pursues other rights, in order to reach the widest possible readership. As with a traditional publisher, authors may negotiate to keep their subsidiary rights, such as foreign language, audio, and other derivative rights.

My only problem with this is the “normally” and “perhaps.” A hybrid publisher should absolutely publish in both print and digital formats. It should also deal with foreign and audio rights, even if it does so by working with a trusted partner.

7. Provide distribution services. A hybrid publisher has a strategic approach to distribution beyond simply making books available for purchase via online retailers. Depending on the hybrid publisher, this may mean traditional distribution, wherein a team of sales reps actively markets and sells books to retailers, or it may mean publisher outreach to a network of specialty retailers, clubs, or other niche-interest organizations. At minimum, a hybrid publisher develops, with the author, a marketing and sales strategy for each book it publishes, inclusive of appropriate sales channels for that book, and provides ongoing assistance to the author seeking to execute this strategy in order to get his or her book in front of its target audience. This is in addition to listing books with industry-recognized wholesalers.

Distribution is the one service you’ll have great difficulty doing yourself. Even if you think the bookstore channel is less important, you’ll still want somebody to work with the airport bookstores, bulk order providers like 800-CEO-READ, and overseas English-language distribution in geographies like the UK, Australia, and India. I’m of two minds about the need for a sales force — while working with distributors is essential, the value of “push” marketing for books is steadily attenuating. As for publicity, you might be better off working with a traditional PR firm than the publisher’s publicity staff, which are balancing your needs with dozens of other books.

8. Demonstrate respectable sales. A hybrid publisher should have a record of producing several books that sell in respectable quantities for the book’s niche. This varies from niche to niche; small niches, such as poetry and literary fiction, require sales of only a couple thousand copies, while mass-market books require

more.

This could be sharper — what, after all, is “respectable?” But if you’re considering a hybrid publisher, get sales numbers for some of their books that are similar to yours. Bottom line, if they can’t show that they can help a book to sell, they’re not really much of a service company. A publisher that publishes quality books should have some notable successes to point to.

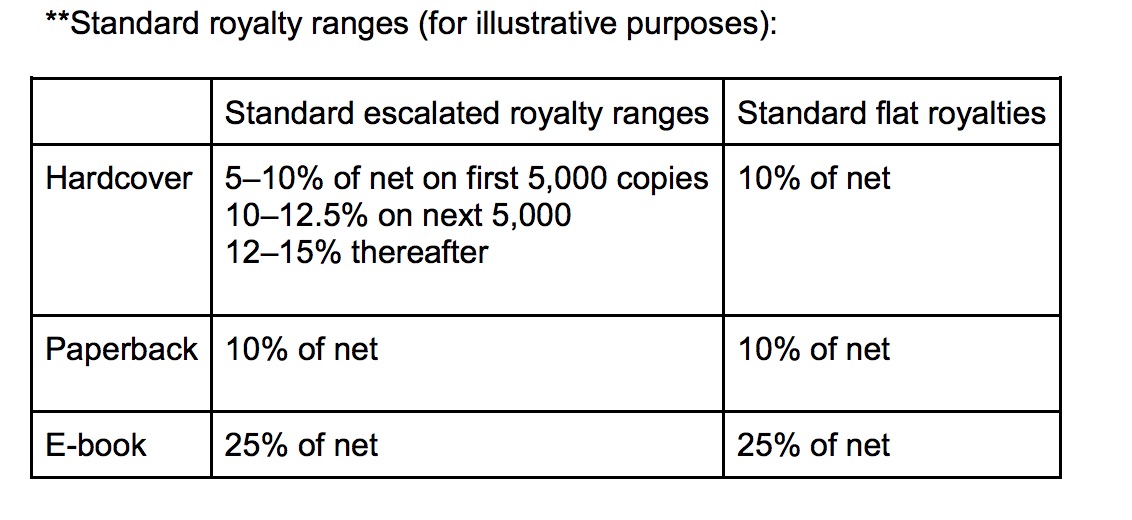

9. Pay authors a higher-than-standard royalty. A hybrid publisher pays its authors more than the industry-standard* royalty range** on print and digital books, in exchange for the author’s personal investment. Although royalties are generally negotiable, the author’s share must be laid out transparently and must be commensurate with the author’s investment. In most cases, the author’s royalty should be greater than 50% of net on both print and digital books.

IBPA’s document lists the standard royalty ranges from traditional publishers.

Your hybrid publisher had better be paying you more than that, since they’re not giving you an advance.

These criteria are necessary, but not sufficient, for you to make a decision on how to publish

I commend IBPA for creating a set of criteria that makes it easier to screen out true hybrid publishers from pretenders. The next step has to be some sort of certification program, so you can be sure that the publisher you’re considering is operating in line with these criteria.

But even if your publisher lives up to this standard, you have important questions to consider before choosing a publishing partner. Some charge you for book printing — how much do they want? Must you buy all of their services (for example, copy editing, proofreading, marketing, and cover design) or can you substitute your own? How fast can they produce quality work?

I recently went through this process with authors on two separate book projects, and I was startled to see the wide range of prices and offerings from competitors in this space. These companies are far more diverse than traditional publishers, and their strengths and level of value vary widely. Since you’re not picking a partner based on the size of the advance, you’ll want to pick based on the qualities of the publisher — the quality of the books they produce, their editorial staff, their process, and their price. Because the partner you choose is going to make a big difference in whether your book accomplishes your goals.

Josh, thanks for this excellent post. I’d like to expand on a couple of things, if I may.

The criterion about having a publishing vision / mission is important because this is a longtime principle of the industry which service providers and vanity publishers don’t observe. It matters for editorial as well as marketing reasons (and also for more “sentimental” reasons to do with values and identity). First, you want your publishing team to have a deep understanding of the material they are working with. Developing literary fiction or poetry is very different from developing travel guides, cookbooks, children’s books, etc. That’s why larger publishers have a range of imprints, often staffed by different teams – it isn’t just about branding, it’s about specialism.

Selling and marketing those various types of books well also depends upon specialist experience and relevant relationships with retailers. Now, you quite rightly point out that some traditional publishers have pretty wide-ranging lists, but that’s ok. You don’t have to be as narrowly focused as, say, O’Reilly to have an identifiable vision. At LifeTree Media, we publish trade non-fiction books that help, heal and inspire. That encompasses a lot of categories, from health to business to self-help, but you won’t find textbooks, poetry, puzzle books or gardening guides on our list.

Regarding your point about imprints and ISBNs, I’m curious to know whose ISBN Greenleaf used in publishing your book, and whether it went into their distribution pipeline. It’s easy to stick a different logo on a book spine, but the ISBN identifies the publisher as the source and supplier of that title. By definition, if you are an author whose book is published under your own ISBN, then you are the publisher of record for that work, i.e. your book is self-published. Of course, there are many good reasons for wanting to publish under your own imprint! Some hybrid publishers also serve self-publishing authors in this way, as we do through our Assisted Self-Publishing program. We just can’t put those books into the trade as ours.

Regarding your very good point about “respectable sales”, I am rolling my eyes and groaning in rueful agreement. This was a much-discussed item in our committee meetings as we were hashing out the criteria. The sad truth is that a great many traditionally published books sell in very low quantities. A publisher – traditional or hybrid – may have a spectacularly unimpressive track record, but while that may make an author wary of signing with them, it doesn’t affect their legitimacy. They’re still a publisher, just an unsuccessful one.

You make good points. And my book with Greenleaf was under their ISBN and their sales force.

Tell me more about your editing services please