Ask Dr. Wobs: How to bust out of rigid academic writing boxes

Today’s question comes from a university student who thinks the professor is putting him in a box with instructions on how to write a paper. But how big is that box, really?

Dear Dr. Wobs,

Re: Avoiding the structure of academic writing

I’m taking a political science writing class at Ohio State, and we have a paper due in a few weeks. The professor assigned us a format we must follow: a one paragraph introduction, 4-8 supporting paragraphs, and a conclusion.

I just read your book, and I want to use the ideas you talked about to improve my writing/argument. My problem is that the required structure is inhibiting my ability to be proud of my writing, and forcing me into a dry, stale paper. Is there any way to combat this academic structure without blatantly disregarding the requirements of the paper?

Will

Dear Will,

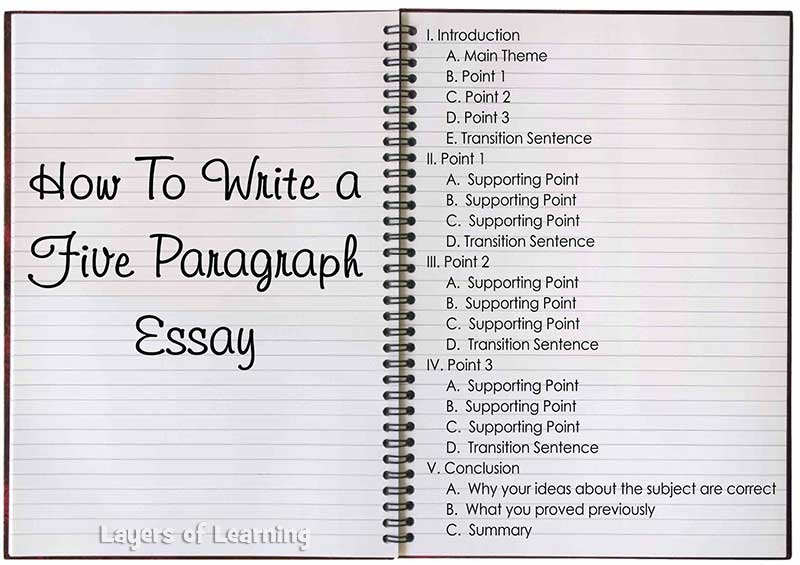

I sympathize. Overly rigid frameworks like the dreaded five-paragraph essay have taught writing students how not to think.

But let’s solve your problem. My basic philosophy with regard to writing formats is to understand two things:

- Why is this format the way it is?

- How can I do a good job in this format (or despite this format)?

For example, a tweet is 280 characters. It’s short for a reason. So don’t write War and Peace in it. A report starts with an executive summary. It’s there to help people see what they’re getting. So go with it, don’t subvert it.

In this case, the reason that the professor has given you this format is to communicate to you how long the piece should be (six to ten paragraphs) and that it needs to start with an introduction and end with a conclusion. If you write this way (and everyone else in the class does, too), it makes it easier for the professor to grade the papers, since they will be, at least on the surface, similar. The other reason for this format is to train you to include an introduction in what you write, which is a good habit to get into (but see my recommendations on what to start with below).

In this case, the most important reader is the professor, so violating these rules is probably inadvisable. I wouldn’t start with a personal story, for example.

But let’s take this requirement apart.

You should pick a topic that is appropriate for the class. That’s not too rigid.

As I describe in my book, you should start everything you write with a statement that summarizes your argument. For example “As we saw in the recent Supreme Court hearing, the polarization of politics in the nation is undermining our political institutions.” Or something similar. The whole point of the opening paragraph is to tell people what’s coming. I would call this common sense (and common journalistic practice, as well), so I’d hardly call it a rigid requirement. If you’re having trouble getting started, just put something down and come back to it when you’ve written a draft.

Whatever your paper is on, you’re going to have to assemble some facts, statistics, examples, and arguments in favor of your position, as well as arguments rebutting opposing positions. You can organize these “nuggets” into a loosely structured “fat outline.” This will help you get things in order.

Once you’ve done that, you can pick the ones that you think are best are write them, in whatever order makes sense, and in whatever style works for you. It doesn’t have to be dry and stale.

Based on this suggested format, you’ll end up with about 500 to 1000 words. If you aim for that word count, you’ll end up with the number of paragraphs your professor suggests. The “4-8 supporting paragraphs” suggestion is very loose — just ignore it and write what makes sense to you. You’ll end up hitting the prof’s target. And if what you write is too long, it’s easy to cut something.

So now we’ve dispensed with the paragraph requirement, which isn’t much a guideline anyway.

What about the conclusion?

Well, students (and all writers) have trouble with endings. They tend to write “As I said, blah blah blah” which is dull and repetitive.

What I recommend for conclusions is to go further and ask questions like “If this is true, what should we do?” or “Because of the case I made, this issue has broader significance.” (I wrote about better conclusions here.) Endings like this show the reader that what the read was worth reading, since it leads to more interesting truths.

Let’s take stock. Is this requirement really inhibiting you? You need to start with a statement that sums up the argument, and you can revise that after you’ve drafted the paper. You need some sort of argument with evidence after that, which you can write in any order you want. And you need a conclusion that shows that you can think.

To me that sounds like a pretty loose format that won’t necessarily lead to a “dry, stale paper.” You can write almost anything you want, in any style you want, and still satisfy that requirement.

Think about readers, not boxes

Imagine that you get a present. It’s a cube-shaped box about 18 inches on a side. Would you be disappointed?

What could be in the box?

It could be a puppy.

It could be a set of keys to a new car.

It could be a boxed set of Stieg Larsson novels.

It could be an engagement ring with a whole lot of packing material.

It could be just about anything. The size of the box shouldn’t be a disappointment, if it could be filled with anything you can imagine.

If you’re writing something that has to fit in a box, forget the box. Think about the reader. What does she want to know? What would thrill her and get her thinking? What research would it take to convince her?

Concentrate on that. If you’ve got something interesting to say, you can probably figure out a way to fit it in the box.

But you won’t write something brilliant if you worry about the box, rather than the goodies inside.

As a professor who stresses clear writing as much as technical chops, I find this post interesting.

Yes, you are right: professors need to provide some semblance of what’s expected via a rubric and a template. Odds are that students will request one or both if the professor doesn’t provide one.

Still, there’s plenty of room within those boundaries to write well. I’d also argue—as many have—that constraints can be a good thing.

Fourteen lines divided into three stanzas of four lines each and a final couplet, rhymed a-b-a-b, c-d-c-d, e-f-e-f, g-g, is about as rigid a format as one could imagine, yet Shakespeare managed to spin it into over 150 sonnets.