All merger announcements are bullshit, Dell-EMC included

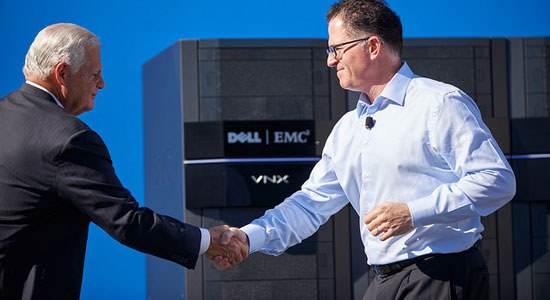

The fantasy world of merger announcements bears no resemblance to the reality of mergers. Michael Dell’s post about the Dell-EMC merger is a fine example.

Why do companies merge? There’s always language about “complementary skills and assets,” but that’s always bullshit. There is always language about “serving customers better” but that is also bullshit. Companies merge for growth — period. It’s not about customers. It’s about money.

There are two basic merger scripts, none of which you will ever read, and both of which are bad for customers:

- When two large companies merge: Our growth has slowed. So we will add our customers to their customers and our products to their products. To make this work we have to cut costs, so people will lose their jobs. Customers should expect a rough ride while we painfully rationalize our different systems for doing things and the person here that you were used to counting on loses their job. After a few years of that, things will go back to pretty much the way they were, if you’re lucky.

- When a large company buys a small company: We want something they have, and buying it is the only way we can get it. If you’re a customer of the large company, you won’t notice much. If you’re a customer of the small company, you’re screwed. If their product emerges from the merger at all, it will be starved of resources, twisted to meet the acquirer’s needs, or priced way higher than it used to be. Or all three.

Companies cannot say these things, of course. So instead, they make empty promises. I’ll show this with Michael Dell’s post “Three Resolutions for our Customers and Partners.” I’ve admired and worked with many great people at Dell and have a lot of respect for Michael Dell, who bravely and sincerely backed his employees’ use of social media to reach out to customers. But when it comes to public announcements in the wake of a merger, he has to follow the script like everybody else.

Here are some excerpts from the post with jargon and weasel words in bold italic, and my commentary in brackets.

[W]e announced a landmark transaction to combine Dell and EMC to create an enterprise technology powerhouse with the values of a startup: innovative, nimble, and customer-centric. [Making companies bigger does not make them innovative or nimble. Dell has been above average on “customer-centric,” but I doubt this merger will improve that.]

The combination of Dell and EMC will position us to create more customer and partner value than any technology solutions provider in the industry. We’ll be best positioned to maximize legacy investments with leadership in storage, servers, virtualization and PCs. And best positioned to build a bridge to the future through leading innovation in digital transformation, software-defined data center, converged infrastructure, hybrid cloud, mobile and security. [Let the jargon commence, starting with customer value and finishing with a laundry list of technobabble. And lots of “positioning,” not be confused with “posturing.” Each of these jargon words means something to somebody, but taken together they just say “now we have more technology products.” And when a large company says it leads in legacy as well as the future, it’s not nimble, it’s sprawling.]

This is our time to accelerate the development of groundbreaking new technologies that will support you in a connected world that is ripe with opportunity and disruption. [Does “a connected world that is ripe with disruption” mean anything? This is the textual equivalent of a rice-cake — you appear to be chewing something, and yet there is not actually anything there. ]

[W]e are making three resolutions today:

– To make you, our customers and partners, the core of everything we do. . . .

– To accelerate innovation. . . . We will implement an innovation strategy for each business that will allow it to reach its full potential. . . .

– To create a future where we can do incredible things. Our future will build on the foundation of EMC’s deep relationships with large enterprises . . . . Today, Dell is the only provider of end-to-end IT solutions and is gaining share across core sectors outpacing the market, and financially strong. . . . In the future, our technology will create jobs, hope and opportunities on a global scale. The possibilities are limitless. [Dell’s three resolutions are generic and vague. Are you ready for the implementation of an innovation strategy to reach full potential? The last resolution is about market share — a benefit for the company, not the customer. The last two sentences are like a political speech: rousing and yet meaningless.]

Disclosure Regarding Forward Looking Statements. This communication contains forward-looking statements, which reflect Denali Holding Inc.’s current expectations. In some cases, you can identify these statements by such forward-looking words as “anticipate,” “believe,” . . . “should,” “will” and “would,” or similar expressions. Factors or risks that could cause our actual results to differ materially from the results we anticipate include . . . [Obviously this is the disclaimer, and obviously no one reads it. It is the longest one I’ve ever seen, 677 words in total. It basically says “You cannot count on any of these promises.” And I keep reading “Denali” as “denial.”]

Excluding the disclaimer, I count 377 out of 506 meaningful words, for a meaning ratio of 75%. That could be far worse. But the emptiness of this announcement is deeper than the individual words. Of course, it’s a merger announcement. What do you expect?

This is a great pickup — At first I thought it was a joke! — “And I keep reading “Denali” as “denial.”

On the extreme end of 2 large companies “merging” for the sake of “money…” I was part of a company that was acquired through a “merger of equals.” We were an automotive parts company with lots of various divisions from a long history; they were a heavy-trucking company, spun off fairly recently by an even-bigger company.

Class 8 trucking was in the TOILET in the late 90’s. What became apparent after the “merger” was that our board sold the company out to finance the other company’s short-term loses. They sold our company’s divisions, one by one, to cover balance sheet hemoragging for the next few years. My division (the largest) was the last to go, 3 years later. We were finally spun out into private equity, then sold to a French company about a year later. (It became apparent that my position was to be eliminated, and I found greener pastures. They hired someone for my old job 3 months later, and then cut him loose 3 months after that.)

So, yeah, the “merger” I went through took a great, 100+ year-old company, which was a good place to work, and destroyed it. The C-level execs all split about $50M to sell us out, so I’m sure they think it was an unqualified success. The merger was sold to the investors with the caveat that my company’s CEO would become the CEO of the merged company in 2 years. One year later, they pulled the ripcord on his golden parachute, and gave him $19M to get lost. The whole thing should have been criminal.

There was lots of bullshit along the way. My favorite was how the CEO sent out a company-wide email allaying rumors that we were not considering any offers of being bought, just one month before the announcement. Then, of course, it was sold as a merger of equals, which was all complete bullshit. The sub-C-level execs started leaving right after the announcement, which should have alerted naive people like me as to what was really happening.

Synergy. We’re going to have synergy.

I dunno – HP and Compaq was a pretty great concept… 🙂

While the concept may have been good that women you see a lot on TV lately refused to delegate and could not micromanage the details.

There is another common reason for mergers: survival. Like David K’s company (comment above/below), it is a case of merge or die. And I include being taken over as corporate death, and often such mergers, like that of David K’s company, end up indistinguishable from a forced sale.