AI and the loss of certainty

Bear with me: I’m about to tie mathematical logic to artificial intelligence. (I promise, no actual mathematical knowledge will be required.)

In 1931 the brilliant mathematician Kurt Gödel pointed the apparatus of mathematics at itself. He was able to prove that in any mathematical system powerful enough to do simple arithmetic, there would always be statements that were true, but could not be proven.

Gödel’s “Incompleteness Theorem” shocked the mathematical establishment. Prior to this, the objective of mathematicians was clear. For any conjectured statement, mathematicians could either attempt to prove it true, or prove it false. Presumably, by working cleverly enough, either one or the other would be possible.

Take Goldbach’s conjecture, which states that every whole number greater than two can be written as the sum of two prime numbers. You could set out to prove using logic that this conjecture is true, or you could find a (presumably very large) whole number that can’t be written as the sum of two primes. Before 1931, nearly every mathematician believed that those were only two possible outcomes.

But the Incompleteness Theorem implied a third possibility: the conjecture could be true, but with no possible proof. For a mathematician laboring to prove anything, there was the lingering possibility the problem under study was undecidable: neither provable nor disprovable.

At first, there was a conceptual loophole. All of Gödel’s undecidable statements were basically ways of encoding paradoxical statements of the form, “This statement is false.” So as a mathematician, you could still believe that only “weird” statements were undecidable, and any “normal” statement of actual interest to mathematicians, like Goldbach’s conjecture, was either provably true or provably false.

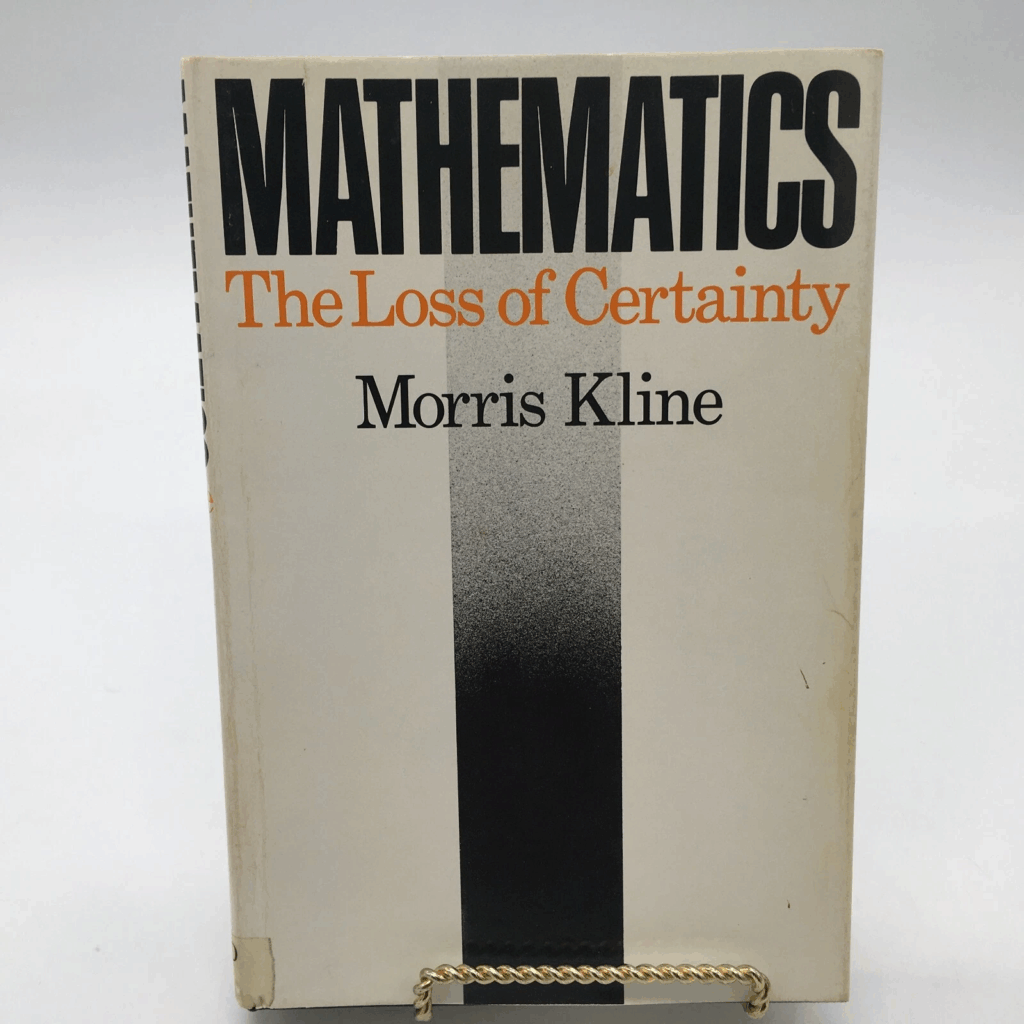

Unfortunately, real mathematics didn’t conform to this dream. Mathematicians showed that some important problems of actual research interest were undecidable. This was a matter of quite a lot of discussion when I was studying mathematical logic in the 1980s. The mathematician Morris Kline published Mathematics: The Loss of Certainty in 1980, likening mathematics to a religious quest, one that was now having a crisis of faith.

45 years later, are we going to lose faith in the idea of truth?

The real world is not a world of certainty. Statements aren’t either true or false; instead, at best, they’re either “almost certainly true” or “almost certainly false.”

Take, for example, the statement that the polio vaccine prevents polio. Scientific studies show that the recommended three doses are 99% effective in preventing infection from polio. You can argue whether this is “proof,” but it’s about as strong evidence as you can get. Most people would accept a statement like this as true.

Or consider the statement that president Franklin D. Roosevelt said, in his 1933 inaugural address, that “The only thing we have to fear is . . . fear itself.” (Obviously, he wasn’t afraid of the Gödelian undecidability.) FDR’s inaugural address was filmed; you can listen to the recording. Thousands of people heard it. It’s about as close to an undisputed fact as you can get.

For many decades, we learned to depend on authority figures like journalists or scientists to tell us the truth. If the scientific community said that the polio vaccine prevents polio, or journalists and historians told us that FDR said the only thing to fear was fear itself, we believed it.

What changed, starting in the late 1990s, was that nearly every statement, true or not, ended up being accessible online. When Google came along in 1998, you could search any purported fact and hope to find sources that would tell you if it were true, false, or not yet known.

Of course, Google couldn’t tell you whether to believe what you read. But once again, you could fall back on authority. If the web site of the Centers for Disease Control told you something was true, it probably was. If The New York Times published a fact, you could depend on it. If an unknown site or one with a questionable agenda, like InfoWars, or known for satire, like The Onion, was the source, you knew to be skeptical. (There’s a whole book about to understand how to evaluate statistical truth, Fact Forward: The Perils of Bad Information and the Promise of a Data-Savvy Society.)

This was a particular kind of certainty — perhaps not mathematical certainty, but a certainty that the world was constructed from generally accepted truth and you could recognize it when you saw it.

Of course, many of us are no longer searching for truth with Google results, we are searching with ChatGPT or Perplexity. Even if we still search with Google, there’s that oh-so-convenient AI-generated summary at the top that purports to tell you what the truth is, abstracted from the search results.

Unfortunately, you can’t count on the certainty of what an AI search tells you.

It may find only sources that you would never depend on if they weren’t filtered through the AI search. You may not even notice that you’re now depending on “truth” from some random commenter on Reddit, or a Wikipedia article written by some anonymous person.

And there’s another source of false truth: AI summaries that tell you what a source says, even though if you were to look at that source, you’d find that it doesn’t actually say that.

AI has even been known to invent nonexistent sources.

Or there may be sources that careless or malicious actors have deliberately placed to be indexed and offered up by AI tools, such as deepfaked photos, audio, and video.

These are all reasons to be skeptical, but AI results are presented in such a way as to be convincingly authoritative, even when the underlying data (or lack of data) aren’t. Smart, skeptical people track down the original sources (both Google Gemini and Perplexity make that easy, while ChatGPT will do it if you ask it to). But people in a rush don’t.

When you transfer your idea of authoritative truth to an algorithm design to satisfy you, regardless of the truth, certainty is going to take another blow.

Mathematics has never been the same since Gödel punched a hole in a domain that used to be filled with certainty.

Now reality seems poised to take the same path.

Be cautious. Because where certainty once was, now there is only an algorithm that wants to please you.

Brilliant. Kept me reading all the way through.

Amazingly botched source name. Proof of algorithm falliblity? I’m not coffeeexuberantb4c957d41d. Can you see my actual name?