A Knewton critique: Why computers shouldn’t teach calculus (or anything else)

Isi, my teenager, is a college student taking calculus. The teacher is assigning homework from Knewton, an online learning system. I’ve been helping with the homework. Now I can see why computers can’t teach college courses — and why tools like Knewton are not just destructive, they’re evil.

The old way of teaching calculus worked pretty well

Once upon a time, nearly 40 years ago, I taught calculus. I taught recitations (interactive classes of a few dozen students who’d attended the professor’s large-scale lectures). In other semesters, I taught the whole class through lectures. One summer I taught it to a bunch of Navy grad students who were all older than me.

These experiences do not qualify me as an expert on teaching calculus, but they do inform the opinions I’m sharing here.

There are three things you need to do to teach calculus correctly. (Unsurprisingly, these are the same three things you need to teach just about anything else.)

You need to explain concepts, like rates of change, instantaneous slopes, and the idea of a derivative. To develop intuition, students need to know the meaning of what they are doing.

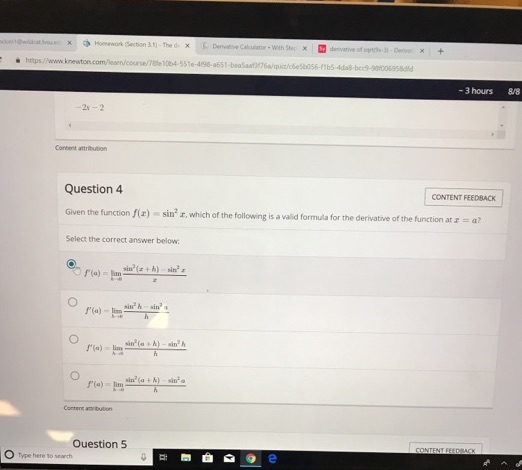

You also need to explain the rules. Students need to understand and memorize key formulas like the difference quotient and the chain rule and learn when and how to use them.

Finally, the students need practice. There’s a difference between knowing why and how to sing, and actually singing. So they need to actually work a bunch of problems. In calculus, the more complicated problems often involve a lot of algebra.

If you’re doing this kind of practice, you make mistakes. You can make conceptual mistakes, like applying the wrong rule. But you can also make many other kinds of mistakes: sign errors, failing to carry a number down to the next step, multiplying 12 x 7 and getting 86.

When I was grading calculus homework, you’d get no credit if you made a conceptual mistake. But you’d get partial credit if you understood the concept and applied it correctly, but then made arithmetic or simple algebra errors.

This type of grading encouraged the students. If the answer was cos(x) and you got -cos(x), you knew you were understanding the concepts, and you could work on getting the rest of the calculations error-free with practice.

Perfect students who were facile with math got great grades. Slower students who needed to practice got good grades, and got better with practice. Students who didn’t understand the concepts or didn’t put in the work got bad grades, which they deserved.

By broadly penalizing error, Knewton undermines learning

In Isi’s calculus class, the teacher appears to be explaining the concepts well. Isi is also quite capable of understanding the rules and how they apply. I was gratified to hear Isi say at one point, “I actually like this math stuff.” I think Isi’s logical mind and fastidious attention to detail is a good match for math and that is a good sign, since the kid wants to major in computer science.

But in Isi’s class, the homework is on Knewton. Here’s how Knewton works:

- You get a bunch of assigned problems in each section.

- You cannot skip a problem.

- You don’t get the same problems as your fellow students, so you cannot compare your approach.

- You read the problem and work it on a piece of paper. You use a sophisticated formula entry tool to type the answer into the web page.

- If you get the answer exactly right, Knewton gives you a little dollop of encouragement (“Great job!”) and may even reduce the number of other problems you need to do.

- If you get the answer wrong, Knewton gives you a hint and you can take another try.

- When the answer is wrong for any reason, Knewton generates more similar problems, and you have to work those to finish the homework. You cannot skip any. You just sink deeper and deeper.

The Knewton company has big ambitions. It has raised $137 million in funding. Its former CEO, Jose Ferreira, had said that the company could replace teachers and human intuition. As he told NPR, “We can take the combined data power of millions of students — all the people who are just like you — [who] had to learn a particular concept before, that you have to learn today — to find the best pieces of content, proven most effective for people just like you, and give that to you every single time.”

In the same article, educational consultant Michael Feldstein said that Knewton was selling “snake oil.”

I can’t address what Knewton is doing in all those other courses, but I can judge what it is doing in calculus, which is to demoralize students and interfere with learning.

Imagine for a moment that you are doing a calculus problem that involves 20 steps, any one of which you might get wrong due to a simple transposition error that has nothing to do with conceptual knowledge or the rules of calculus. It has taken you 15 minutes to do the problem. Now it’s time to type that answer into Knewton.

If you get it wrong, you know Knewton is going to give you even more homework to do. That could be four more problems just like the one you made the mistake on. You just lost an hour or more. And heaven forbid you make a sign error on one of those problems.

You cannot get partial credit.

You cannot skip the problem and come back to it.

What you can do is go to Wolfram Alpha and type the problem in there and get the right answer without doing any work.

If you are extraordinarily moral, you will work the problem on your own, check it on Wolfram Alpha, and then type it in. But you won’t be getting the learning that came from making mistakes.

Making mistakes is a fundamental part of learning anything, whether it’s salsa dancing, tennis, writing, or calculus. We learn by doing things wrong. The teacher shows us what we did right (yay!) and where we went awry (ah, I see, I’ll do that better next time). This is normal, natural, and essential — it combines learning with the simplest and most obvious psychology of learning.

Despite the cheery mechanical pronouncements that Knewton makes when you get a problem right, students have a very strong incentive not to make mistakes, even if those mistakes are tiny errors. It’s as if you got an electric shock every time you used the backspace button when writing. Except this time, the penalty is having to do more of the same work that you just made a mistake on — without much in the way of diagnosis.

While Knewton’s public statements indicate that they can create a conceptual map of where students’ problems are, in the case of calculus, there are simply too many ways to go wrong. If you make a mistake on step three of a 20-step problem, you might go wrong in any number of different ways. And you’re not allowed to just give up and move on.

As so often happens in today’s automated society, Knewton replaces a manual system (teachers correcting papers) with an automated system that works poorly and chews up the student’s psyche in the process.

That’s no way to teach, and it’s no way to learn, either.

AI is practicing on us

Before AI can get good, it has to be bad. That is, it has to be worse than doing things the old people-intensive way.

AI gets better by making wrong guesses, just like people do.

But when it comes to learning, training AI by making guesses about what students are doing wrong is abuse. Students don’t pay college tuition to be fodder for AI experiments.

People need to make mistakes. Until computers can identify and act on all of those possible mistakes, teachers are going to be better than machines at teaching.

There’s a special place in hell for the small minds who refuse to give partial credit.

There’s a special place in hell for the small minds who punish all mistakes equally.

That made me smile.

Josh – you write:

Despite the cheery mechanical pronouncements that Knewton makes when you get a problem right, students have a very strong incentive not to make mistakes, even if those mistakes are tiny errors.

I’d love to see what Knewton’s data says about the matter.

I Knew it!!! I completely Hate Despise Knewton, Ivee learned to be nice but Knewton is Demonic, Completely right! Enjoying Our Mistakes,,,Making us Suffer frekn Demonic,,,In Feedback I am Constantly giving them my hell…but Im sure No Human reads it!!! omg Looks like I will FAIL MY CALCULUS for My AA in May!! BS….thanks To KNewton I may be homeless, I was counting on that AA for Summer,,,But the Corporate Greedy Pigs don’t Care for Anyone!! Sick world!! I will Send to My Instructor! ,,,I Work for 8hrs at 95% & MISS A PROLEM DOWN TO 70% OR SO …UR ANGRY …AT WORK ARe U TOLD U MUST WORK ANOTHER 4 hrs Because u missed a Spot???

AI I Knew a human could not have made these problems, also there is no Alternative onlly there way or Answer or Tufff s,,,,,,

Too bad the company is private – it should be a screaming short!

It is amazing how close Science Fiction of the 70’s and 80’s got this abusive AI scenario right……

I’m 48, returning to the university to finish a degree I started years ago. I am using Knewton in my calculus course, and find it very helpful. It is annoying to get a problem wrong due to an algebraic error, and have to do more as a result, but it makes me pay more attention to what I’m doing next time around. We also have Knewton based quizzes and tests, and have to scan and upload written work. Most of the grade comes from the written work, and there are times where I received credit for written work when a minor mistake caused Knewton to mark it wrong. If someone were just sitting there plugging problems into Wolfram, they wouldn’t make it past the first quiz. I also like that when you do get something wrong, a detailed explanation of how to do it correctly follows. And if you keep getting it wrong, more instruction, often with videos, is given.

It sounds as if the Knewton approach is similar to speaking English louder and louder to someone who barely speaks the language, in hopes it will aid comprehension.

In college I completed 5 semesters of calculus and a semester each of matrix math, differential equations, and statistics. I appreciated the professors and graders who took your grading approach and loathed those who did not.

As you pointed out, Josh, there is a world of difference between a conceptual error and a calculation (algebraic or numeric) mistake. In the learning process, knowing why an answer is wrong is more important than it being wrong in the first place. When we had our homework graded line-by-line and discovered where we made the errors, it helped us in two ways: knowing where we tended to go awry in our calculations and increasing our confidence by ironing out any faulty concepts. An effective learning tool diagnoses and distinguishes such reasons.

The line-by-line grading is tedious, and that’s why graders are employed in the university to handle those tasks. I understand that your daughter is a high school student, and funding is likely not available for such a position.

Something using black-and-white reasoning like Knewton might be useful to the faculty in grading lots of tests quickly, once the students have acquired the skills, or it can be used for assessing a student’s knowledge level (albeit both inaccurately, as calculation errors beset the best of us). Without the discerning corrective diagnosis, Knewton fails as a teaching tool. And homework is a teaching tool.

One way Knewton can be used as a teaching tool is to change its process. This is how I would reprogram Knewton: When the student chooses an answer, it is recorded to the teacher, who accumulates the aggregate results of the students. A student should be able to skip around to other problems and circle back, if they please. Another slot should be given at each problem: a comments section, where a stuck student types in the quick explanation (I got stuck at the _____ step) or enters their last step in symbols. The teacher can then see which problems are problematic (pun intended, you’re welcome), and then the next day the teacher can review these step-by-step on the board.

Giving students more of the same problems they can’t complete correctly in the first place, WITHOUT telling them precisely where they went astray, is purely ridiculous, let alone frustrating. It may even ingrain bad habits or faulty thinking that you’re trying to fix in the first place.

If you require perfect practice, you have failed as a teacher.

Thanks for your note.

My child is a college student, not a high school student, as I wrote in the blog post. I never mentioned Isi’s gender.

You are absolutely correct in most of what you say above and correct about most platforms. It is not correct to say that computers can’t be useful aids in education, though, so if that’s your message, you’ve overstepped pretty big time. to say “Knewton is selling snake oil” is not the same thing as “computers are not useful tools ever.”

I said computers shouldn’t teach calculus. But only an idiot believes computers aren’t useful tools for teaching in other contexts. They’re just not good at recognizing answers that are only mostly correct. Yet.

You are mistakenly broad in your claim then.

If you want to be precise, you are mistakenly broad in your interpretation. I said computers shouldn’t teach. I didn’t say they shouldn’t be used at all.

Computers can and should be used for teaching, but it’s ujst possible we agree about more than we disagree about, and we’re talking past one another.

At ALEKS (www.aleks.com) we partnered with the world’s finest math and chemical educators to teach using computers effectively (Knewton is a poor imitation designed to extract Venture Capital funds from greedy and ignorant investors who don’t understand the gritty details of moving the needle in math and science in higher education).

First, Take a look for example at the general chemistry sequence at Emory University. Talk if you like to Dr. Douglas Mulford or Dr. Tracy McGill. I’ll wait. http://chemistry.emory.edu/home/undergraduate/overview/ECCP.html

Also, Before wasting your breath with “But that’s not during the semester…” know that they continue to use the same technology during the entire general chemistry sequence. Talk to them if you really want to understand this issue about which your original piece was overly broad and unnecessarily negative.

See how many dozens of universities are using ALEKS Preparation for Calculus to make certain the large hall of eager learners is more homogeneous with respect to mastery of the necessary body of basic concepts and skills. The greatest piano teacher in the universe can’t teach Horowitz to an ignorant lecture hall half full of students who don’t understand music theory.

Second, some students need to see a concept or skill only once ( or possibly zero times because they know it already) because they are reviewing forgotten material from earlier in their schooling. it’s inefficient for a human to teach a basic topic that a computer can teach while making sure students who have forgotten it see it again and again until they get it. Teaching the art of the perfect free throw to Steph Curry and Shaquille O’Neal is not the same task, and today’s teachers don’t have time to teach both all semester long.

Finally, any claim about what computers can’t do should be made carefully as a general matter. An early mentor of mine from Intel in the 1980’s told me this, and I never forgot it “Given sufficient time, brains, and money, humans can make computers do some amazing things. Don’t listen to the “can’t do it” people. They are almost always wrong.”

everything you said was spot on. Knewton can bite my

I am having similar problems with Knewton. My son is challenged with high functioning autism.He loves math, but this program has taken his love for math. It has sent him into serious anxiety attacks. I have had to seek professional help for him. I am now seeking legal recourse.

In my own experience – having taken Calculus in-person in high-school, and online in college, I much prefer Knewton’s online homework. Beyond that, I believe it’s a superior system in general, and will only continue to improve over time

Features like instantly generated worked out solutions to each question and the sliding scales of homework solve massive issues with traditional teaching. Grading is a massive waste of time for teachers, and it’s impossible to assign the right amount of the right homework when each student has unique strengths and weaknesses. So much time is saved when competent students aren’t forced to do busywork, and struggling students get the instruction they need before it’s too late and they’re failing a math class because they don’t have the prerequisite skills. It’s hard to overstate how important those features are.

You bring up the argument that mistakes shouldn’t feel bad. I really think it speaks to the failings of American education culture that you can hold this opinion. Of course getting problems wrong should feel bad. If you never get punished for errors, you’ll never stop making them. You’ll never learn how to quickly check for mistakes, how to know when to check for mistakes, or in general how to ensure you’re right when it counts.

I’ll admit that partial credit would allow the system to be tuned more finely. It’s actually quite likely Knewton or a similar program will soon advance to the point it offers intelligently awarded partial credit. It could even diagnose more specifically the errors you tend to make, before giving you refreshers and focused practice to help you iron them out. I have to imagine that’s the future of homework, but Knewton’s current state, while crude, has its advantages.

Comparing it to my high school experience, I would often skip and skirt around homework, and end up with a passable conceptual understanding but weak effective skills, as I was slow and made many mistakes. I didn’t have much motivation beyond my own interest in the concepts. Now, because of Knewton’s features, I respect the value of the homework. Since I feel doing the homework is the most efficient way to prepare for tests, I don’t feel the need to cheat or skip homework, and the homework is more rewarding as I do it. It feels good to be rewarded for competence and persistence rather than obedience.

After looking at all the improvements in online homework, it’s really hard to imagine a future without it. It may not work as well for some students, and there will still be a place for in-person instruction, but for most, the details and economy of scale make it invaluable. Questioning it as you have is a lot like questioning the invention of the telephone because the audio quality isn’t great, and talking in person works just fine. You may never come around to it, but the world already has.

I am currently taking applied calculus online and Knewton Alta is being used for everything! Homework, quizzes, tests, our final, and get this the teaching as well!!!! Our teacher is not giving any lectures live, prerecorded or otherwise. We have to read the book from openstack (free) and then use Knewton Alta to fill in the rest. If I’m lucky I get a quick 2-5 min youtube video instruction on the subject, but mostly its more ready like the book. Math is not my strong point but I’ve been a solid B student in all my regular classes up until now. Its so frustrating when I follow the instruction on how a particular problem should be solved and I still get a wrong answer. I’ve been scratching my head as to why I paid for a class not actually being taught by the teacher the school is paying.