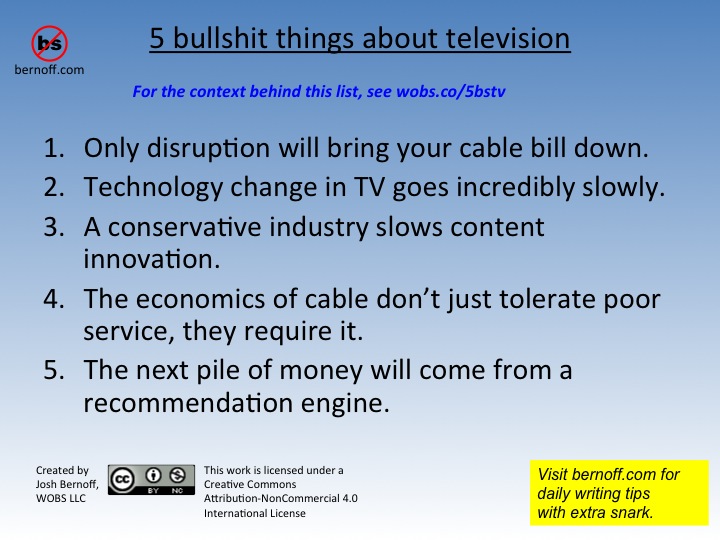

5 bullshit things about television and the reasons behind them

I studied the television industry for more than a decade. It doesn’t work the way you think it does. Since TV is a highly visible but stodgy industry ripe for disruption, it’s a great topic for #5BullshitThings, highlighting industries that work in incomprehensible ways and why they do.

I studied the television industry for more than a decade. It doesn’t work the way you think it does. Since TV is a highly visible but stodgy industry ripe for disruption, it’s a great topic for #5BullshitThings, highlighting industries that work in incomprehensible ways and why they do.

I’ll explain your bloated cable bill, why TV programs are so crappy, and why it’s so hard to find anything good to watch.

Only disruption will bring your cable bill down.

Here’s why your TV bill keeps going up. Networks travel in bunches with a common owner (for example, Disney owns ABC, ESPN,the Disney channels, and ABC Family). These media companies keep multiplying channels and on-demand program collections so they can charge more to your cable or satellite operator. Your operator has learned that as long as they bundle the channels you want with all the other channels, they can keep raising the price, about 5% per year. So the channel bundle keeps growing, both in size and cost.

Verizon’s attempts to unbundle, lame as they are, have already upset the industry.

Hulu and Netflix break the cycle — or at least they will until they get big enough. Then they’ll start raising prices and trap us into the next bundling cycle.

Why it happens: Because you can’t live without television. And because there’s no incentive for cable operators and networks to change things so long as you’re willing to pay.

Technology change in TV goes incredibly slowly.

It may seem as if new TV technologies like streaming, digital video recorders, video on-demand, and HDTV got here quickly. But they could have been here five or ten years earlier. I learned that when a cable operator said “we’re ready to pilot a new technology,” it really meant “wait a year.” This led me to formulate Bernoff’s first law of TV technology:

No matter how slowly you think a cable operator will deploy a technology, it will go slower than you think.

(Bernoff’s second law of TV technology says that even if you know Bernoff’s first law, cable companies still go slower than you think. Bernoff’s third law is that the only thing slower than a cable company is a telephone company.)

Why it happens: The TV value chain rigidly ties together advertisers, producers, networks, cable operators, and consumers in a shared moneymaking scheme. Any technology disruption requires all these players to rework not only the way they produce TV, but the contracts that distribute the money. Nobody wants to rock the boat.

A conservative industry slows content innovation.

It’s pretty risky and expensive for an advertiser or network to back something new. That’s why we get a constant parade of sitcoms, procedurals, and news programs that look just like what we got last year. That’s what wins at the advertising upfront.

But think about it for a moment. Consider some programs and formats that broke the status quo and became huge hits: Sesame Street, Star Trek, All In The Family, M*A*S*H, Hill Street Blues, American Idol, The West Wing, Seinfeld, Fox News, Lost, The Sopranos, Mad Men, Orange is the New Black. They all broke rules, looked incredibly risky, became wildly profitable, and generated imitators. But advertisers and networks don’t like to bet on programs like this because the risk of failure is high. People get promoted when these shows win, but they lose their jobs when the shows fail and failure is far more common.

Why it happens: Entertainment businesses looking for security always bet on programs similar to what’s out there. Only a powerful, slightly unhinged producer with a vision can get somebody to take a flyer on it. The advertisers and hangers-on arrive later, once it’s proven.

The economics of cable don’t just tolerate poor service, they require it.

It’s expensive to run a cable company. You’ve got a massive physical plant with wires that continually need upgrades. You’ve merged so many times that your operation is a mosaic of incompatible technology. You’ve got thousands of employees to get in line. And you’ve got to deal with rodents.

On the other hand, even after the advent of cord cutters and phone company competition in many parts of the country, cable still has pretty close to a monopoly on local service. It’s a pain in the neck for a subscriber to get rid of cable; inertia dictates that most people won’t leave. After all, their TV works great nearly all of the time. It’s only the occasional installation or change in service that causes them pain. So the cable company does only what it must to keep service acceptable for the majority of customers.

Why it happens: Financially, the smartest thing to do is to invest the minimum possible, try to keep people from leaving, and raise prices slowly. When the service shortfall gets catastrophic, cable companies eventually need to upgrade their service systems. They make the investment required to go from awful back to merely bad. And when they do, you can bet they’ll seek maximum publicity for doing the right thing.

The next pile of money will come from a recommendation engine.

In the 90s and 00s, a company called Gemstar had a chokehold on the TV industry. Its patents on electronic program guides meant that you couldn’t distribute a broad channel lineup without paying Gemstar for a guide license.

But television isn’t about the schedule any more. The biggest problem is searching your recorded programs, on-demand programs, Netflix, Hulu, Apple TV, Roku, Playstation, or whatever sources you have to find something to watch. That’s broken. Whoever creates a workable recommendation engine for all this content will make a bundle, because they’ll influence your viewing choices more than anyone else.

Why it happens: The new world of TV is too fragmented for any one guide to attain Gemstar-like dominance. The Google of television will be the company that makes TV search and recommendation easy.

—

See also: 5 Bullshit Things about book publishing.

What should I take on next with #5BullshitThings? Make a suggestion in the comments or send me an email at josh at bernoff dotcom.

The economics of cable TV have been altered by the advent of mega-dollar deals for the pro sports leagues. Following the money that makes it happen reveals virtually all of the new TV money is actually going to player salaries.

This is not completely true, Brian. The pro sports deals boost the cost of ESPN and other sports channels. And those are the largest individual channel costs in cable. But they are not close to the majority of the cost.

Yep pretty much. Ideally at some point internet and wifi will be enough to access every program available. I would see disruptive technology as something that combines both better picture (like a mini-projector attached to your computer which give great picture at all hours) along with more selection (like you said, a search engine or recommendations) ease of search (touch screen or better remote) and all at a price like $10-$20 per month. Live events like UFC are a little more difficult to get on a system like this but maybe in the future all can be got in an all in 1 package.

A recommendation engine? You mean like YouTube? Seems like Google could easily roll the YouTube engine into a personal recommendation engine for a broader set of media and deliver the selection through a phone. The Chromecast device might be the key. Connecting to various data sources to collect titles, etc., would be difficult, but it could be done and Google already has the AI to handle our preferences. And Google has the advertising engine to pay for the service.

I agree that Google is well positioned to do this, but don’t agree that the YouTube recommendation engine is the right choice. I am talking about something that would recommend a series of professionally produced content to you (thousands of programs) vs. something to amuse you for a few minutes right now (hundreds of millions of YouTube videos). Netflix is closer to having this than Google is right now.

A TV recommendation engine covering all distribution channels is only possible if usage data is available. Netflix is recommendation driven because it has high-quality and precise subscriber usage data. If you subscribe to YouTube channels and (I think) login through Google+ then the quality of recommendations will be higher.

The technology of recommendation engines is pretty accessible now but good usage data isn’t otherwise it would already be available.