15 tips for working happily with publishers during book production

Even when your manuscript is done, the book is not. After you hand in the manuscript, your publisher (or if you’re self-published, whoever you hired to lay out the pages and put it into online bookstores) still has to copy edit the book, lay out the pages, and get it printed and available for distribution.

I’ll tell you a secret: you want to be really good friends with those production people. It’s sort of like a hairdresser. If you’re friendly, they’ll put in extra effort and make you look good. If you’re abusive and shout and scream at them and tell them they’ve screwed up, then you shouldn’t be surprised if the end result doesn’t look quite right.

Long ago, before I became an author or even an analyst, I started and ran print production for a publishing company. While the technology has vastly improved since then, the attitudes of authors and production people are still mostly the same. As a result, I viscerally understand the struggle from both sides.

So I’m going to take that knowledge to give you a few tips that will not only help you be friends with your book production people, but ensure that your book is published with the maximum quality — and the minimum of hassle.

1 Talk with the production people well ahead of turning in the manuscript

Every publisher’s production department has slightly different conventions for how they handle things like text formatting and copy edits. Your production editor (the person in charge of producing the book at the publisher) will likely be willing to spend 30 or 40 minutes with you to help answer questions you may have.

Some publishers don’t allow this. That’s a stupid policy: all it does is make it more likely there will be costly and time-consuming misunderstandings when you hand in the manuscript.

2 Pay close attention to the publisher’s deadlines

Work with your editor or production editor to get clear deadlines. When must the manuscript be handed in? Is there an editorial review, or does it go straight to copy editing? When will the page layout be happening? When will you receive books, and what is the publication date?

Be extremely aware of not just when things are due, but when they’ll be expecting you to review things and get them back with comments. Because if you take a vacation in the middle of the page proofs stage, you’re either going to have a stressful vacation or a late book.

3 Request an early look at the inside page design

Well before your publisher accepts your manuscript, you should get a look at what the design for the pages will look like. Typically, you send the publisher some sample text, and they lay it out so you can see what headings, body text, bullets, and figures will look like. Ideally, your sample text should include all elements that are in the book, such as sidebars, chapter titles, and subheads. If something about the design repels you, this is when you complain, not when they’re in the midst of laying out 200 pages in the design.

4 Allow yourself time for manuscript completion

You should have at least a week between when your manuscript is complete and when you hand it in. This is when you check and fix inconsistencies, add footnotes you may have forgotten, and fix the other little nagging things you were leaving to the end.

5 Use styles to indicate things like bullets and head levels

Some authors unused to the production process use Microsoft Word formatting to reflect their intentions: features like tabs, extra spaces, manual line and page breaks, underlines, blank lines of text between paragraphs, and bold to indicate headings. Don’t do that. It’s ambiguous and creates extra cleanup work for the page layout people.

Instead, use Word’s heading styles, formatting that automatically puts blank space after paragraphs, and styles like bullets and numbered lists to indicate what you want. If you have two head levels within chapters (sections and subsections), use different MS Word head levels to indicate them.

And don’t use two spaces after a period. It makes you look like a dinosaur, and the publisher will just have to strip them out . . . a process that sometimes introduces errors.

6 Try to turn in a grammatically perfect manuscript

It’s tempting to assume the copy editor will find all your errors. But the copy editor’s job is far easier if you’ve found and fixed as many spelling, grammar, and consistency issues as you can before you turn in the text. Copy editors are human; if you make them find ten times as many issues, they may miss one or two, and it’s more likely to get into print.

7 Build in time for fact verification

Do a pass on your manuscript to verify all facts (for example, the number of mobile phones in the world). And plan on getting a review from the people you interviewed to make sure you’re quoting them correctly. It’s best if you’ve completed and gotten approval from 90% of those folks before you turn in the manuscript; this avoids the need to mangle text that’s already been through copy editing. So build in time for those reviews.

8 Pay special attention to graphics

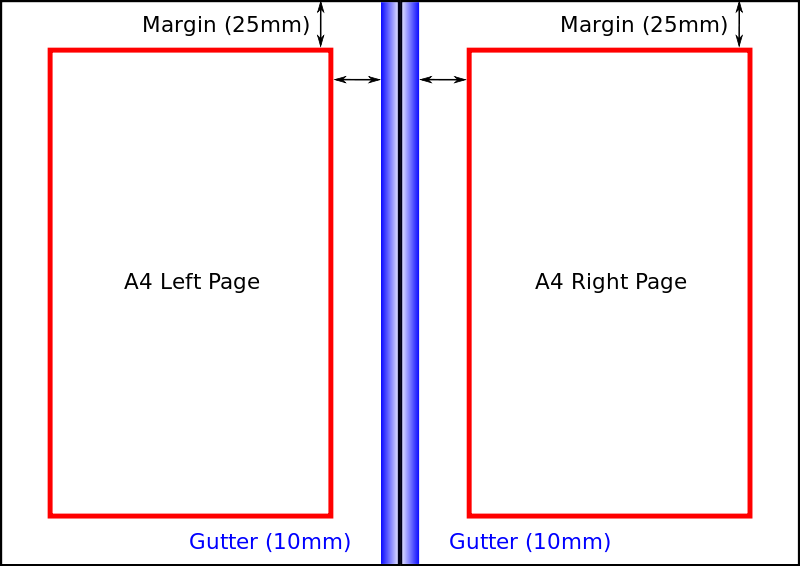

Graphics are a pain. If anything goes wrong in your production process, it’s usually a graphic. So communicate with your publisher about graphics formats, colors and shading, and how you’ll be handling figures and tables. Don’t just assume they’ll create pretty graphics out of your crude sketches — ask first, and determine if you need to hire your own designer. Here’s a checklist to help you get you and your publisher on the same page about graphics.

9 Understand copy editing

The copy editor’s job is to find your errors and inconsistencies. Your job is to respond and decide what to do about them. Don’t get mad. Learn the rules, like the compound-adjective rule. And decide whether you use the Oxford Comma or not. (You probably should, but whether you do or not, be consistent.)

10 Avoid the urge to make last-minute changes

Each change introduces the opportunity for more errors. So keep late changes to a minimum.

If an error gets into print, it’s a pretty good bet it happened because you edited something after the copy editor was done with it.

11 Be eagle-eyed in reviewing page layouts

Every publisher and page layout person I’ve ever worked with makes mistakes. Head levels are wrong, there are widows, graphics are in the wrong place, running heads are wrong, or tables are a mess.

You can get mad about this. Or you can carefully check all of your page proofs and tell the publisher how to fix things. Just don’t assume it will all be perfect on the first try.

12 Care about the index

It takes time to do an index. Allow for it. If you have notes for the indexer, make them clear at the copy edit stage.

13 Printing takes time — allow for it

It takes a long time to get into a printer’s schedule and get a book printed. And that delay has become even longer because of pandemic-related supply-chain issues.

You can question how long the process takes. Or you can trust that your publisher probably has better connections with printers than you do.

One way to avoid long delays here is to hit all your deadlines. If your late manuscript pushes the pages-to-printer deadline by a week, you could miss your printing window and push the print date out by a month.

14 Recognize the difference between books-available date and pub date

You’ll have books in your hand within days of the end of the print run.

But it takes time for books to get into warehouses and bookstores. That delay can be a month or more. Go ahead and take preorders, but don’t assume the book in your hand means it’s ready for people to buy on Amazon or pick up at your local bookstore.

15 Savor the moment

You and your publisher have one thing in common: you appreciate a quality book.

So enjoy the new-book smell and the way it feels when your book comes out. If you’ve made friends with your publisher — and your publisher’s print production people — you may even have gotten to this point without cursing or tearing your hair out.

Great advice! Thanks!