11 key planning tips for writers and the psychology behind them

Crappy writing springs from crappy planning. Like an architect, plan before you build. On a project that takes weeks or months to write, spend at least one day on planning. Follow these planning tips to maximize your chance to create something great.

In this post, I show you how to lay the groundwork for a writing project like a book, a Web site, a manual, a research report, or a strategy document. This is your checklist if you’d rather spend your crunch time at the end making it better, rather than just crawling across the finish line. A modest amount of effort now will help you avoid a lot of pain later. (For quick reference, I include a wall-chart at the bottom).

1 Nail down goals.

What to do. Identify who your readers are (audience), your objective, the action you want to generate, and the impression you’d like to leave (Use this acronym to keep it straight: Readers, Objective, Action, iMpression = ROAM).

Why it matters. Writing is completely different based on audience and objectives — are you writing for CEOs or college students? Unless you consider these, your piece will head off in the wrong direction.

Why you avoid it. You’d rather write than think about writing; you have an unconscious (but poorly formed) idea of these elements in your head already.

2 Manage research.

What to do. As you plan your research, build a sortable spreadsheet of interviews targets, research tasks, contacts, statuses, and dates. Track both your own research and what you assign to others.

Why it matters. Interviews take a long time to line up. Web research needs time and concentration. Research first, then write, or you’ll end up with crap that needs rewriting.

Why you avoid it. You think research is easy and most of what you need is already in your head. You won’t realize you’re wrong until you’re hip-deep in a draft full of holes.

3 Identify your editor.

What to do. Identify someone smart whom you trust and recruit them to edit. Explain when drafts will appear, what sort of feedback you need, and how quickly you’ll need responses. Estimate their time required and get them to commit.

Why it matters. You need an editor with a different point of view from yours, preferably someone who can think like your readers. Your editor compensates for your blind spots, reveals where you’re going wrong, and gives you new ideas.

Why you avoid it. Nobody really loves criticism. You think you’re already a good writer and don’t want someone else to meddle.

4 Line up contributors.

What to do. Identify experts who can help you like a stats whiz, a graphic artist, or a marketing copywriter. Approach them with specific requests (what material to create, deadlines, how you will review or rewrite the material).

Why it matters. You don’t know everything. Experts can make your writing more credible and well-rounded.

Why you avoid it. You think you don’t need help.

5 Involve gatekeepers early.

What to do. There’s always somebody with final approval, such as executives, lawyers, and publishing company editors. Confirm who they are, and don’t leave anybody out. Get their buy-in on outlines and parts of drafts that will concern them.

Why it matters. If you identify them early and get them involved, they’re less likely to block your project or require major rewrites at the end.

Why you avoid it. The people who must approve your project are busy, high-level people and you’d rather not create conflict with them.

6 Build a realistic schedule.

What to do. Figure out the interim stages: outlines, parts to be drafted, complete drafts, and final reviews. Your schedule must define not just when to complete these stages, but exactly what you will deliver on those dates. Pad with extra slack at the end.

Why it matters. Without interim deadlines, things slip to the end. This shortchanges review time and makes it harder to create a quality result. (It also tends to ruin your weekends.)

Why you avoid it. Interim deadlines require you to complete work sooner. Everybody is busy and would rather put things off.

7 Lay out a structure.

What to do. Figure out the parts of what you will write. Will there be an executive summary? Will it include graphics? Three chapters or ten? What’s the table of contents?

Why it matters. You need the shape of the final document clear in your mind so you can create content to fill it.

Why you avoid it. A framework creates barriers; it’s much easier to just write bits and pieces and glue them together.

8 Write a summary.

What to do. It seems counterintuitive, but you should attempt to summarize the (imagined) document in three or four sentences, even before you write it. Then rewrite the summary based on the actual content as you complete each draft.

Why it matters. A summary focuses your mind on what the document is supposed to be doing.

Why you avoid it. Summarizing content you haven’t written yet seems impossible.

9 Create a promotion plan.

What to do. Figure out how you’ll reach everyone who needs to see your document. If it’s a blog post, how will you promote it and make it rate high in searches? If it’s an internal document, will you email it to people, post it on an Intranet, or get an executive to talk about it? Books need full promotion plans in place well before you’ve written them.

Why it matters. Why bother writing something big unless you can get it in front of the maximum possible audience?

Why you avoid it. Promotion is harder than writing and requires a marketing skill set you may not have.

10 Prepare to maintain.

What to do. Build a plan for who will revise the document and how frequently in response to changes in the area that it covers.

Why it matters. Documents aren’t static. As markets evolve and facts change, they become dated and obsolete.

Why you avoid it. A big deadline to complete the document motivates everyone, but nobody loves maintenance. You’d rather not think about maintaining the document once it’s written.

11 Extend what you create.

What to do. Figure out if your document is a template or springboard for similar pieces. Will there be sequels and spinoffs? Can others learn from what you created?

Why it matters. You learn a lot on a big project. Ideally, you can take advantage of that knowledge in other projects.

Why you avoid it. It’s simpler to think of your work as one standalone piece.

Want more insights like this? Follow me on twitter, read the posts below, or scroll down to sign up for daily writing tips with extra snark.

- 10 top writing tips and the psychology behind them

- 5 ways that powerful writing helps your career

- How to write boldly when you are afraid

- The Iron Imperative: Your reader’s time is more valuable than yours

- Where bullshit comes from: an analysis

- Dealing with management bullshit: a parable

- Resisting groupthink: a parable

- How I can give you the courage to say what you mean

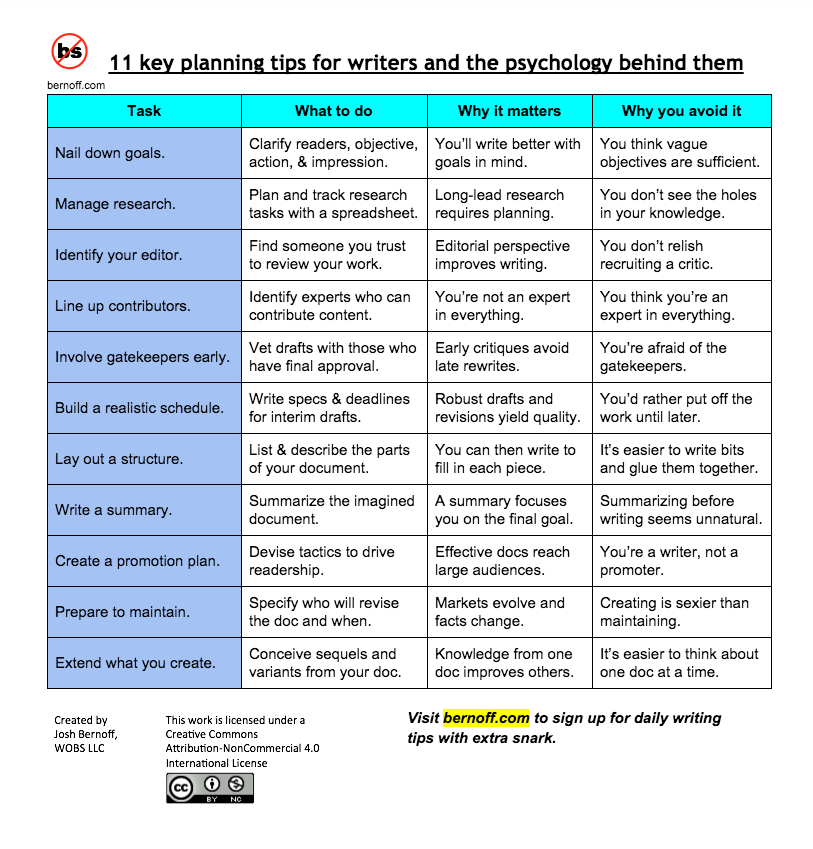

Here’s a wall chart for you. Print it out and hang it up by the place where you write.

Oh, Josh, you are speaking directly to me. I wouldn’t say my writing is crappy due to a lack of planning, but it’s not as good as it could be. Thanks for the kick and the chart. Yes, I’m printing it out and yes, I’ll use it.

In the past, I wrote summaries after I’ve done my drafts. Now I do the reverse, like you said. And it worked better! Thanks for all your tips.

This is so timely and a must have! I’m one of those who tend to freewrite before I do a draft, but FINALLY learning how to make a more in-depth outline that makes it a breeze to nail the first draft. Thanks for sharing this, Josh!

Thanks.

You have typos.

One is in your tip 11.

Can you find it and could I have been more to the point?

Love your work.

Goldie

Thanks. Fixed it.

Thanks.

Your next typo is in another part of the list.

It is poetic.

Typographers know it’s a typo.

Others may not see it.