With Hurricane Harvey approaching, the Weather Channel wastes copy on weather porn

Hurricane Harvey looks like a devastating storm. But with the media deploying superlatives so frequently, is there any capacity for alarm left for this actual emergency? I analyze the lead hurricane article from The Weather Channel for precision, clarity, and effectiveness. The lesson here: context is crucial when describing a potential disaster.

Start with this: if you are in coastal Texas near Corpus Christi, get out; if you’re anywhere near there, take precautions and expect flooding. This Hurricane is no joke.

But predicting hurricane tracks is imprecise. There is an uncertain possibility of an unknown amount of disaster. Humans have trouble analyzing risks like this. It has been 12 years since a hurricane of this magnitude hit the U.S. coast, and as a result many readers won’t be able to effectively react to this news; they may want to trust in their ingenuity rather than forecasters.

This is the environment in which media must report on the hurricane. Their best tools are colorful charts. As for text, they can trot out well-worn superlatives that have lost their bite and statistics that readers have trouble putting in context. It’s the shakiest journalistic writing at the worst possible time.

Analyzing the lead hurricane piece from The Weather Channel

Let’s take a look at what The Weather Channel wrote as of Friday morning. In what follows, I show weaselly qualifiers and intensifiers in bold and passive voice in italic. I’ll also underline statistics without context. My commentary and translation follow each passage.

Hurricane Harvey Expected to Strengthen to Category 3 Status; Strongest Texas Coastal Bend Landfall in At Least 47 Years Likely; Extreme Flood Threat

Hurricane Harvey continues to intensify and will be the nation’s first Category 3 landfall in almost 12 years tonight or Saturday morning, poised to clobber the Texas Gulf Coast with devastating rainfall flooding, dangerous storm-surge flooding and destructive winds this weekend, before taking a strange, meandering path spreading heavy rain toward Louisiana next week.

Commentary: That’s a 23-word tripartite title — when you’re seeking the important news on what to do, you must instead take extra time to parse this SEO-besotted monster. In the title and lede, The Weather Channel cranks up the intensifiers: “extreme,” “intensify,” “dangerous,” and “heavy.” When you’re talking about a hurricane, these words are warranted, if imprecise. You have to wonder if they’ve lost some impact after being used so frequently in so many situations, both meteorological and political, in the last few years. Note also the passive “expected to” — this is a theme of this piece, describing things that are expected to happen without telling you who expects them.

Translation: Hurricane Harvey is going to hit the Texas Gulf Coast with the most powerful storm in 47 years. You’ll see floods from both storm surges and rain. Get the hell out of there.

Right Now

After a slight pause overnight, Harvey has reintensified with maximum sustained winds of 110 mph. Harvey is located just under 150 miles southeast of Corpus Christi, Texas, moving northwest at around 10 mph.

Harvey’s central pressure has plummeted once again Friday morning, approximately another 15 millibars in just a few hours as another rapid intensification phase kicks in.

Outer rainbands are already spiraling ashore as far north as Galveston Bay, bringing brief heavy rain and gusty winds.

Water levels along parts of the Texas coast were already 1 to 1.5 feet above average tide levels as of early Friday at Freeport and Sargent, Texas.

Commentary: This is porn for weather geeks. We need context. The bland subhead “Right Now” certainly doesn’t provide it. How much of a big deal are 110 mph winds? How long will it take to get here moving at 10 mph? Is 15 millbars a big drop? Is a storm surge of one foot worth worrying about? The answers are, as far as I can tell: massive; one day; significant; and just wait until tomorrow.

Translation: With 111 mph winds, this storm will cause major damage, and it’s getting stronger. The seas are already rising. Get the hell out of there.

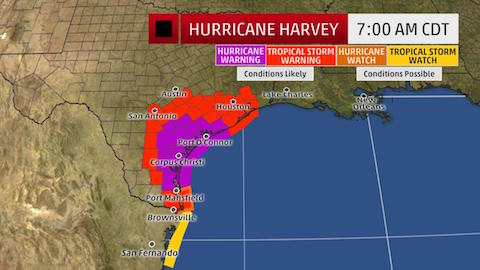

Current Warnings

A hurricane warning has been issued for a portion of the Texas coast, from north of Port Mansfield to Sargent, including the city of Corpus Christi. A hurricane warning means hurricane conditions are likely within the watch area. In this case, hurricane conditions are likely within 12 to 24 hours.

Importantly, tropical storm-force winds may begin to affect the hurricane-warned area above as soon as late Friday morning, making final preparations difficult.

Tropical storm warnings are in effect from north of Sargent to High Island, Texas, including the cities of Houston and Galveston. Tropical storm warnings are also in effect from north of Port Mansfield to the mouth of the Rio Grande River.

The NHC also issued its first-ever public storm surge warning, which includes a swath of the Texas coast from Port Mansfield to High Island. This means a life-threatening storm surge is expected in the warned area in the next 36 hours. This warning does not include Galveston Bay, but does include Galveston Island and the Bolivar Peninsula.

Commentary: Who issued the hurricane warning? Passive voice hides the answer. It’s nice that The Weather Channel explains what a hurricane warning is, but the explanation doesn’t tell you whether it’s a big deal. We also learn that the NHC issued a storm surge warning, but there’s no description of who the NHC actually is.

Translation: The National Hurricane Center has issued hurricane warnings and storm surge watches for nearly the entire Texas Coast, extending inland as far as San Antonio and Houston. Hurricanes means high winds, flooding, and major damage. Get the hell out of there.

Track/Intensity Timeline

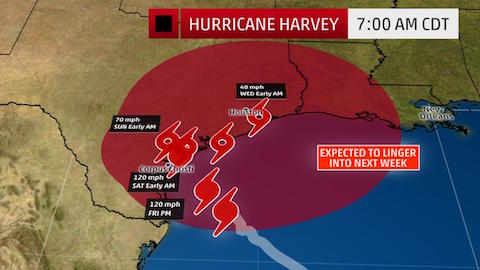

With a favorable environment that includes deep, warm Gulf of Mexico water, and low wind shear, Harvey will continue to strengthen, and will likely be a Category 3 hurricane at landfall along the Texas coast overnight Friday night or early Saturday morning.

After making landfall, Harvey will be caught in a zone of light steering winds aloft that will stall the circulation for more than two days.

Once moving again, potentially by Monday, Harvey’s center may re-emerge over the Gulf of Mexico, opening up the possibility of some restrengthening before a final landfall in Louisiana. But that remains highly uncertain, as stalled or slow-moving tropical cyclones are notoriously difficult to forecast.

This would be the nation’s first Category 3 or stronger hurricane landfall since Hurricane Wilma struck south Florida in October 2005, an almost 12-year run.

Harvey may also be the strongest landfall in this area known as the Texas Coastal Bend since the infamous Category 3 Hurricane Celia hammered the Corpus Christi area in August 1970 with wind gusts up to 161 mph, damaging almost 90 percent of the city’s businesses and 70 percent of its residences and destroying two hangars at the city’s airport.

Harvey will bring a mess of coastal impacts, including storm-surge flooding, high surf with battering waves and damaging winds.

Commentary: Since many readers will not have memorized the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, it helps to explain what it means. Here’s how the National Hurricane Center describes a Category 3 hurricane: “Devastating damage will occur: Well-built framed homes may incur major damage or removal of roof decking and gable ends. Many trees will be snapped or uprooted, blocking numerous roads. Electricity and water will be unavailable for several days to weeks after the storm passes.” But the Weather Channel doesn’t get into this until sharing a historical note of the 12-year run between Category 3 hurricanes. Don’t bury the lede if the lede is a hurricane that might damage 90% of the city’s businesses. It’s also important to address the uncertainty about the storm’s path head-on. Don’t tell us how notoriously difficult these things are to predict; we don’t care. Tell us why that matters — because the storm is going to stall and then might go anywhere.

Translation: The storm will keep getting stronger, and we predict it will be Category 3 when it hits land, causing major damage even to well-built homes and knocking out power for days. After it hits land we predict it will stall, dumping heavy rains on Texas for days. After that, we can’t tell where it’s going, but it could go back out to sea and then hit Louisiana. Get the hell out of there.

Devastating Rainfall Flooding

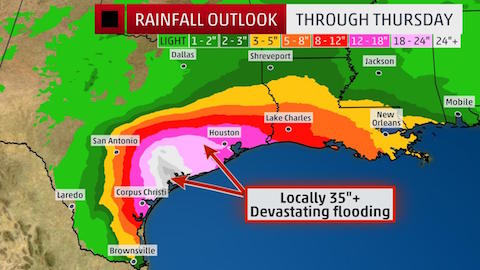

A tropical cyclone’s rainfall potential is a function of its forward speed, not its intensity.

With Harvey stalling for a few days, prolific rainfall, capable of devastating flash flooding will result near the middle and upper Texas coast.

To illustrate this, it’s possible Harvey’s heavy rain may not entirely exit the areas of Texas it soaks until sometime next Thursday, and may not exit the Mississippi Valley until next Friday.

For now, areas near the Texas and southwest Louisiana Gulf coasts are in the biggest threat area for torrential rainfall and major flash flooding, potentially including Houston and Corpus Christi.

Here are the latest rainfall forecasts from the National Hurricane Center and NOAA’s Weather Prediction Center. Keep in mind, locally higher amounts are possible where rainbands stall.

- Middle/Upper Texas Coast: 15 to 25 inches, with isolated totals up to 35 inches

- Deep South Texas, Texas Hill Country east to central, southwest Louisiana: 7 to 15 inches

- Other affected parts of Texas into the Lower Mississippi Valley: 7 inches or less

This forecast is subject to change depending on the exact path of Harvey, locations of rainbands and how long it stalls. Generally, areas along and east of Harvey’s path are in the greatest threat of flooding rainfall.

Among the biggest uncertainties is the heavy rain potential in central Texas, including for the flood-prone cities of Austin and San Antonio. That all depends on how far inland and to the west Harvey tracks and how long it stalls in that area.

Flash flood watches have been issued for much of southeast, southern, and parts of central Texas.

The ground is already quite saturated in many of these areas from what has been one of the wettest starts to August on record.

Commentary: This is just poorly written. It repeats the bit about “rainbands stalling.” And it buries the lede after the innocuous sentence “A tropical cyclone’s rainfall potential is a function of its forward speed, not its intensity.”

Translation: This storm is going to stall over the Gulf Coast. That means you’re going to see between 7 and 35 inches of rain depending on where you’re located. It could go on until Thursday or Friday. The ground is already wet from earlier in August. So the coast and even Austin and San Antonio are going to see devastating floods. Get out of there. (You may want to build an ark.)

What you can learn from The Weather Channel’s writing

The piece continues in this vein for several more sections. But the flaws are the same: passive-voice predictions, weaselly superlatives, and out-of-context statistics. The Weather Channel has violated The Iron Imperative: when the reader urgently needs information, it presents a self-centered ramble of storm porn.

When you need to communicate clearly in a crisis, here are the lessons to take to heart:

- Save the superlatives for the crisis. This storm really is going to be devastating. But The Weather Channel and everything else we read has desensitized us to extreme words, even when warranted. That’s why I call the alarmist media “the boy who cried weasel.” In your writing, save the extreme words for extreme conditions. If others have polluted your environment by overusing these words, fight back with short, clear, pointed sentences and statistics.

- Put statistics in context. This piece is full of numbers. Wind speeds of 110 miles per hour sound dangerous; 35 inches of rain is terrifying. The emphasis should be on what these numbers mean, which demands context. The best context in this article is the description of how Hurricane Celia, a similar storm, damaged 90% of the structures in Corpus Christi. That gets people’s attention.

- Tell us the source of your predictions, don’t hide them with passives. Words like “expected” set off alarm bells. In this case, The Weather Channel needs to either stand behind its own predictions or cite the predictions of the National Weather Service or the National Hurricane Center. Then we know that we can trust that this isn’t just alarmist screeching.

- Make subheads tell a story. Don’t write “Track/Intensity Timeline.” Write “Storm will stall and then dump rain for days.”

- And for lord’s sake, don’t bury the lede. The message here ought to be simple: high winds, storm surges, and devastating flooding are likely, so get the hell out of there. Long titles and opening sentences don’t carry that punch. Just be short and clear and people will get the message.