The “Open Letter Against AI” makes good points, but is ultimately naive

A number of prominent authors, including Benjamin Dreyer and Gregory Maguire, recently published an open letter to the publishing industry. (Read the full version here.)

I appreciate the sentiment. But a number of the recommendations are, in my view, unrealistic.

AI has already been embedded into writing processes, ranging from the grammar tools in Microsoft Word to automated footnote formatting. Some AI practices are more controversial, like AI-generated narration and AI-generated knockoff books.

Some practices that these authors decry is awful. Others aren’t.

Here are some key excerpts from the open letter with my commentary as a writer, thinker on the future of publishing, and analyst of technology.

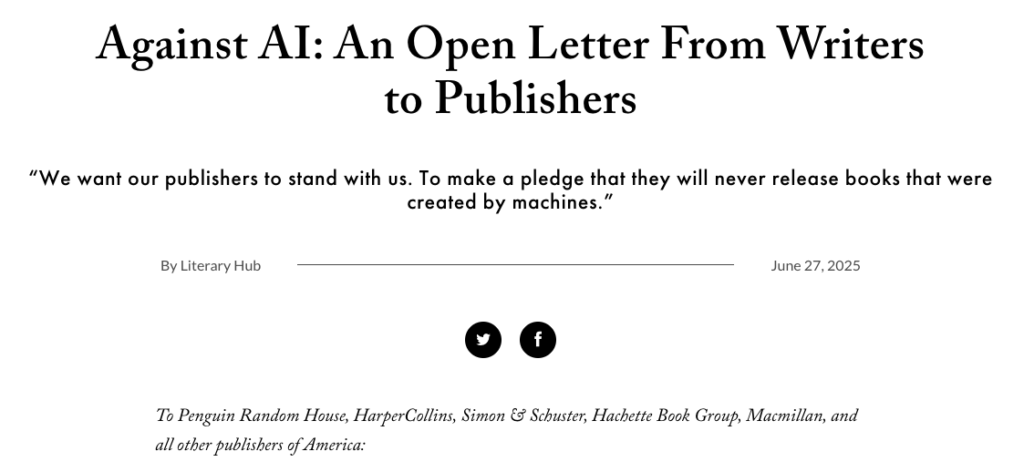

Against AI: An Open Letter From Writers to Publishers

“We want our publishers to stand with us. To make a pledge that they will never release books that were created by machines.”

To Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, Hachette Book Group, Macmillan, and all other publishers of America:

We are standing on a precipice.

At its simplest level, our job as artists is to respond to the human experience. But the art we make is a commodity, and our world wants things quickly, cheaply, and on demand. We are rushing toward a future where our novels, our biographies, our poems and our memoirs—our records of the human experience—are “written” by artificial intelligence models that, by definition, cannot know what it is to be human. To bleed, or starve, or love.

AI may give the appearance of understanding our humanity, but the truth is, only a human being can speak to and understand another human being. Every time a prompt is entered into AI, the language that bot uses to respond was created in part through the synthesis of art that we, the undersigned, have spent our careers crafting. Taken without our consent, without payment, without even the courtesy of acknowledgment.

Like all manifestos, this is a persuasive and impassioned statement of principles. We are indeed artists, and our job is to respond to the human experience. But AI is a useful tool. Using it to write is generally a mistake. Using it to help a writer in the writing process is not. AI is a useful tool. Just as we use computers, word processors, and the internet to help us write now, AI is a tool in our toolbox.

. . . The purveyors of AI have stolen our work from us and from our publishers, too. The hard-working editors and copy-editors and publicists and publishers that cared for and developed and launched the books we’ve written? Their jobs are also in jeopardy, which means that book publishing as an art form—a collaborative art form, nurtured at every stage by the personal touch of a human being—is in jeopardy, too. The audiobook narrators who have breathed life into our stories have already been sidelined by cheaper, simpler AI imitators. To add insult to injury, use of AI has devastating environmental effects, using great amounts of energy and potable water. What happens next?

I agree that AI has ripped off the work of authors. This is illegal and should be prosecuted (and is being prosecuted in many lawsuits). A licensing regime for content is evolving (see the recent Cloudflare announcement). Working with my publisher, I’ve already been paid to license my own books to one of the AI tools. AI built on stolen content is illegal — but future AI is likely to be built on properly licensed content.

We want our publishers to stand with us. To make a pledge that they will never release books that were created by machines. To pledge that they will not replace their human staff with AI tools or degrade their positions into AI monitors.

We call on our publishers to pledge the following:

• We will not openly or secretly publish books that were written using the AI tools that stole from our authors.

This is unrealistic. Authors use all sorts of tools. Asking publishers to police those tools is impractical.

• We will not invent “authors” to promote AI-generated books or allow human authors to use pseudonyms to publish AI-generated books that were built on the stolen work of our authors.

Publishers should agree not to publish AI-generated books, which are, for the part, crap. Amazon has already said they will reject such books, and AI-generated text is not protected by copyright. But there’s a big difference between AI-generated text and text that produced with the aid of AI (for example, in research and grammar checking).

• We will not use AI built on the stolen work of artists to design any part of the books we release.

I assume this refers to cover art. I agree. AI-generated cover art is a bad idea. But what happens if an artist uses AI tools built into a piece of software like Photoshop?

• We will not replace any of our employees wholly or partially with AI tools.

Publishers are commercial entities. Replacing a copy editor with AI is a mistake (I know — I’ve seen AI-generated copy edits that were dreadful.) But if AI can support a copy editor to do the work that two copy editors used to do, the publisher is going to be able to lay off some copy editors. The same applies to other roles. For example, an acquisitions editor could use AI to screen incoming manuscripts and reject those that are clearly worthless, concentrating on those that are more promising. Automation tools have always made business more efficient. AI tools are going to do the same. Given the declining economics of book publishing, increases in efficiency will help it, not kill it.

• We will not create new positions that will oversee the production of writing or art generated by the AI built on the stolen work of artists.

Is this happening?

• We will not rewrite our current employees’ job descriptions to retrofit their positions into monitors for the AI built on the stolen work of artists. For example: copy-editors will continue copy-editing their titles, not monitoring and correcting an AI’s copy-editing “work.”

I find the example misleading. As I described earlier, I expect AI-supported editorial roles to be more efficient. This does not make them “monitors of AI,” any more than a page layout professional is a “monitor of page layout software.” Editorial staff will use tools, including AI tools.

• In all circumstances, we will only hire human audiobook narrators, rather than “narrators” generated by AI tools that were built on stolen voices.

I think people will prefer human audiobook narrators. But if an author wants to produce an AI-generated narration (as Melania Trump has), why is that a problem?

As authors, our future contracts with publishers will reflect these beliefs to every extent possible.

Many of these provisions are unenforceable or undetectable. I think this manifesto is unrealistic.

Some final thoughts

I’m glad this discussion is happening. I’m not so fond of taking inflexible and absolute positions against what is so clearly a massive trend, not just in publishing, but in everything. AI is revolutionizing the world, just as computers and the internet did. Hiding in a purist hole free of this technology is unrealistic and reactionary.

AI vendors must build tools on properly licensed content.

Authors and editorial staff are going to use AI tools to improve the quality and efficiency of their work.

These things are going to happen. The only question is, what do writing, publishing, and reading look like after they do?

Josh, I couldn’t agree with you more, on your thoughts about the Open Letter. I’m spending most of my time on Substack, as a writer, these days; I’m surprised by the blanket anti-AI

stance that most writers are taking. I think it’s naive and even foolish. You nail it with the sentence: “AI is a useful tool. Using it to write is generally a mistake. Using it to help a writer in the writing process is not.”

As a disability advocate and someone who experiences multiple disabilities—including hearing difference, blindness, wheelchair use, mutism, and hand tremors—AI isn’t just a tool for me; it’s a necessity. Without it, I couldn’t have written this reply or read your post. Those advocating for AI’s outright ban are disregarding the reality that many of us rely on it to access basic autonomy, communication, and participation in the world.

I agree that human stories should be told by humans—but some of us *need* AI to reach that space of sharing at all. Removing this access doesn’t ‘preserve’ creativity or integrity; it actively silences a demographic that already faces systemic barriers. The push to ban AI ignores how it serves as an equalizer for disabled people, among others.

This isn’t about resisting regulation or ethical concerns—it’s about acknowledging that for many, AI isn’t a choice but a lifeline. If we’re going to debate AI’s future, let’s center the voices of those who depend on it not for convenience, but for survival and dignity.

Angie, this is so helpful and so useful! TY for taking the time to articulate why AI is so important for you.

These are things we all need to talk about. Blanket statements and concepts regularly roll over the disabled community and so few of us have the platform to speak from, to provide that lived experience angle, that lens of clarity so desperately needed. The choice of tools each individual uses is and should always be, up to the person who needs that tool. Without the need to justify its purpose. But that only happens when people understand that disability isn’t a choice. And accessibility is a human right.