When companies unfairly use Net Promoter Score to rate employees, consumers should game the system

We’ve all experienced it. Companies begging for 9’s and 10’s on the Net Promoter

Score survey, and then punishing employees who don’t get perfect scores when it’s the company that’s at fault.

I don’t just sit and take stuff like this. So today, I recommend a way to boost the employees and hold the company accountable.

Net Promoter is a corporate security blanket

Fred Reichheld of Bain invented Net Promoter to score companies on their ability to retain customers and grow. The idea is incredibly simple: just ask one question of your customers, and you can determine if your company is primed for growth:

“How likely is it that you would recommend this company to a friend or colleague?” Answer on a scale of 0 to 10.

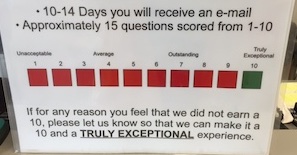

9’s and 10’s are promoters, 0 through 6’s are detractors, and 7’s and 8’s are neutral passives. Subtract the percent of detractors from the percent of promoters and you get the Net Promoter Score, which is supposed to predict whether your company is going to experience growth and customer loyalty.

Even if you’re not a customer-experience professional, you’ve likely encountered the question in surveys from nearly every company you’ve ever dealt with.

There are plenty of analytical types questioning the value of Net Promoter, but it now has so much momentum that it seems impossible to dislodge. Companies cling to it like a security blanket. So of course, their service staff are gaming it.

When companies use Net Promoter to assess partners and employees, these being evaluated game the system

It’s now common for companies to evaluate the performance of their staff and partners using Net Promoter. The creators of Net Promoter never contemplated this way to use it, and it’s not clear that it’s effective. Like any other metric, it creates twisted incentives to game the system. (Goodhart’s law: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”)

I encountered this recently when I got modern, energy-efficient Andersen replacement windows for my house. After the installation was done, I got this message from a customer service person for the installation company, which is an affiliate of Andersen:

[I] wanted to let you know that after each installation, we send an internal survey on behalf of your installer to evaluate their performance in the field. These surveys mean a lot to our crews, as we review feedback weekly. Your answer to the first question, “how likely are you to recommend [name of installer]?” will be the overall score that the installer will receive on this project. We consider a 9 or a 10 a passing score on this question, and we do have feedback boxes if there are any areas you want to highlight or non-install related concerns regarding the process.

You will see this survey come through your email in the next few days. . . . Should you need anything further, or if you have concerns about your install, please let me know as soon as possible so I can do everything possible to earn a 10 on that survey!

This sort of begging for a 10 completely defeats the purpose of Net Promoter and distorts the value of the score. (Who would intentionally design a scale where 9 and 10 are passing grades?)

In this case, the company had a seven-month backlog between the order and the install; the windows were hideously expensive; techs measuring the window spaces made mistakes on two occasions; on the day promised, the installer called in sick; on the subsequent day, the installer identified problems with the windows and had to send them back to the factory for adjustment; and on the next day, they were late because of a flat tire.

On the other hand, the two actual workers doing the installation were precise, efficient, polite, and did beautiful work. When I explained that I wanted the windows completed before I went on vacation, they worked longer hours, including working after dark on the second-to-last day to make sure they could finish on time.

So how am I supposed to use a survey with a single key question to indicate that the installers were great, and the company was not? I’m not going to ding them for calling in sick. The last thing I want is for those hard-working installers to get criticized because of this ignorant use of the Net Promoter methodology.

(Incidentally, I know how they feel. It’s how I feel when I write a great book and get a one-star review on Amazon because the cover was scuffed or the packaging was torn. What does that have to do with what I wrote?)

This kind of thing happens all the time. Companies set up their employees to fail if they’re less than perfect, and then use Net Promoter to calibrate that failure. It’s a crime.

What to do when employees are great and the company isn’t

The answer is simple. Game the system yourself.

If the employees are doing great, answer the Net Promoter question with a 9 or 10. Although the question says “Would you recommend [company name]?” you should answer it as if it says “Would you recommend working with these employees?” If they’re going to use it to evaluate employees, then you have to answer it that way. If the customer service people can game the system, then I, the consumer, can game it too.

Then go right over to Google or Yelp or Angi and give an honest evaluation of the whole process. Those evaluations will reflect the whole experience. If it wasn’t all great, say so.

Those ratings will help your fellow consumers. You’ll get your disappointment off your chest. And assuming you don’t complain about hard-working employees, nobody will lose their job.

Yes, yes, yes! These methods attempt to hold individual front-line employees accountable for the failure of the system itself. And they enervate customers.