Ask the first question

When you’re listening to a good speech, your mind is engaged. The speech ends and the audience claps. Now raise your hand and ask the first question.

When you’re listening to a good speech, your mind is engaged. The speech ends and the audience claps. Now raise your hand and ask the first question.

I first learned this on December 7, 1995. The buzz around Web browsers had become deafening. My Forrester colleagues felt the browser was a threat to Windows and the desktop (and they were right).

I was a brand new analyst and Forrester sent me to Seattle to hear Microsoft’s announcement about what it was doing about the Internet.

About a thousand of us — reporters, analysts, and lots of hangers-on — piled into this huge auditorium in downtown Seattle. I knew nobody. I sat in the second row with a laptop to take notes. The stage was about 7 feet above the audience; I needed to crane my neck to watch as Bill Gates and Nathan Myhrvold explain how they’d become “hard core” about the Internet. There were a slew of announcements about MSN, the new Internet Explorer browser, and partnerships. After about three hours of presentations, they asked for questions.

I raised my hand and Bill Gates called on me. I identified myself and asked why there were no content providers mentioned in any of the pronouncements.

He stared down at me from on high and I could clearly feel him thinking “Who the heck is this pipsqueak?” He certainly knew Forrester, but he didn’t know me. He mumbled his way through some answer that didn’t answer the question and the Q&A continued.

But what happened after that is far more interesting. As the event was ending and most of the audience was leaving, about five reporters came walking down to the front. I talked to Don Clark of the Wall Street Journal and made friends with a couple of guys from the local Seattle papers. And the next day, there were quotes from me in their articles.

I realized at that moment that when you’re watching a speech and the speech ends, you have an opportunity to energize the discussion and become, in a small way, part of the event.

Whenever I watch a speech, now, I think to myself “What is missing? What is next? What does this audience want to know, even if they don’t realize they want to know it?” As I am listening, I am formulating a question. And when the speech ends and the speaker asks for questions, I raise my hand, identify myself, and ask my question. I make sure it is brief, clear, relevant to the topic, broadly interesting, and not self-serving, because people don’t want to hear me talk, they want to hear the speaker answer.

Here’s what that does:

- It breaks the ice. People are usually afraid to ask the first question, since they haven’t thought about it.

- It gives the speaker a chance to elaborate on a point that the audience wants to know more about, usually in a more informal way than the speech. If the speaker has a formal style, this helps humanize them.

- It tells the audience who I am. And often, it gets interesting people to talk to me after the talk.

[tweetthis]Watching a speech? Ask the first question. It’s good for the audience, good for the speaker, good for you[/tweetthis]

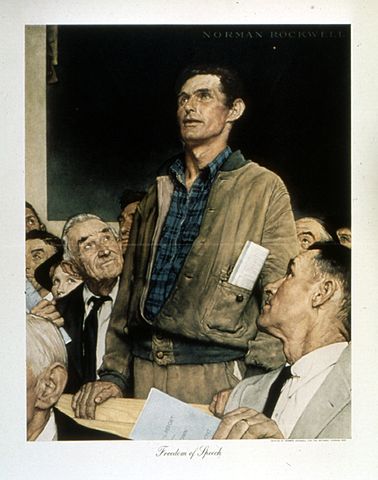

Art: Freedom of Speech by Norman Rockwell, via U.S. National Archives and Records Administration and Wikimedia Commons.